How Jackie Robinson and Paul Robeson Navigated the Red Scare

Alison Stewart: This is All Of It on WNYC, I'm Alison Stewart. The book titled; Kings and Pawns: Jackie Robinson and Paul Robeson in America, transports readers back to the McCarthy era politics, a brewing Cold War, and a racially segregated nation. Take Major League Baseball, which operated under a "gentlemen's agreement" barring Black players from its teams. That is until Jackie Robinson stepped onto the field. His ascent to fame after breaking the color barrier in America's most patriotic sport placed him in an uncomfortable position with another great Black American, Paul Robeson. Robeson was a lawyer, an actor, and a political activist committed to pointing out America's flaws. Even though, as we learn in the book, Paul Robeson had advocated for the inclusion of Black players in the league just four years earlier. Kings and Pawns was written by Howard Bryant, the author of more than 10 books, and he served as NPR Weekend's Edition sports correspondent. Publishers Weekly says the book astutely demonstrates personified Black Americans' internal conflict between patriotism and protest. Kings and Pawns: Jackie Robinson and Paul Robeson in America, is out now. Tonight there is a talk at the Jackie Robinson Museum, not that far from here, at 6:00 PM. Welcome back to the show, Howard.

Howard Bryant: Alison, good to see you.

Alison Stewart: When we're thinking about their legacies, these two men's legacies, what is often overshadowed or overlooked that you wanted to correct with this book?

Howard Bryant: Well, I think one of the things that I really wanted to highlight was Paul Robeson himself. Just a giant of an American, an unbelievable talent, as you were saying, in addition to everything you said before, one of the greatest college football players of all time.

Alison Stewart: You're right.

Howard Bryant: He played in the National Football League. He's also a lawyer, opera singer, all of the things. I just-

Alison Stewart: A fellow.

Howard Bryant: A fellow. Exactly. Then as we talk about Jackie Robinson integrating the major leagues in 1947, Paul Robeson integrated Broadway in 1943, with Othello. To this day, still a record. 296 performances for a Shakespeare production.

Alison Stewart: Wow. So, it's interesting. In reading part of your book, it hit me that Paul Robeson grew up on the East Coast, and Jackie Robinson on the West Coast. How did that affect the way they thought about America?

Howard Bryant: It's a great question, and I haven't really thought of it that way, in terms of it-- I think the way that I really considered them was the generational connection.

Alison Stewart: The generational.

Howard Bryant: That Robeson is 21 years older than Robinson. When you have this collision in 1949, where they are in their lives, Paul Robeson is, at one point, is the most famous Black man in the world, in terms of his reach. Jackie Robinson in 1949 is the hope of what is possible in a segregated society. Robeson has already, I think one of the things that really had bothered me in terms of the narrative had been that Jackie Robinson had destroyed Paul Robeson's career. That was not true. Robeson had already coming out of World War II, this country was changing, and getting deeper into the Cold War, into loyalty oaths, all the things that sound very familiar today.

Loyalty oaths, an attack on American patriotism and citizenship. Robeson had really begun to ratchet up his criticisms of the violence against Black soldiers coming out of World War II. In addition, his politics were very much anti-capitalist. They were very much socialist. He had been affiliated, Friends and had a lot of connections with the far-left and Communist Party and such, and this country turned on him.

Alison Stewart: It's interesting that you said the 21 year difference. If you put that with the East Coastness of him growing up in Princeton, which is where they used to send the Southern sons up. [laughs]

Howard Bryant: That's right. That's right.

Alison Stewart: Up, and everybody knows about Princeton and how-- was it? It was Woodrow Wilson-

Howard Bryant: Wilson. Yes, was the president at the time.

Alison Stewart: -was the president and resegregated everything.

Howard Bryant: In the federal government.

Alison Stewart: Yes. That really affected him.

Howard Bryant: 100%. That is the thing. People said, "What radicalized you?" Well, growing up in Princeton radicalized him. Robeson was such a phenomenal character in that-- I love the similarities between the two men because the question that I had asked when I was working on this with both of them was, "Where did it come from? Where did that toughness come from?" With Robeson, absolutely, he attributed it to his father. We backed down from no one.

Growing up, when you think about his politics, the way he talked about growing up in Princeton, and then of course later, Somerville, New Jersey, but in Princeton, it was very, very clear that the Black class was supposed to be the permanent underclass. Even for all of his greatness, and all of the school and Rutgers that he made famous, all of the things that he had done, one of the things that he had said in his phenomenal autobiography, Here I Stand, in 1959, that the resentment that he had felt was always greatest when he had achieved.

That he had known that he was expected to not compete. That, "White America did not expect to compete with us." When he did, even though he made everyone around him better, he could feel the resentment.

Alison Stewart: The name of the book is, Kings and Pawns: Jackie Robinson and Paul Robeson in America. In the preface you write, "America, in the summer of 1949, was consumed by fear, convinced it was being culturally and politically infiltrated by agents of the Soviet Union. Yet the sentiments of the McCarthy era had been building for years." Howard, how did the United States arrive at a moment when citizens were questioning one another's loyalty?

Howard Bryant: Yes, it's really fascinating because as a-- I mean, I consider myself of the Cold War generation. There's no question about that. For me, the Cold War had always been international. It was the Olympics. It was the USA versus the Soviet Union. It was the 1980 hockey team, and it was the day after, and it was the missile gap and all of that, but this period, this period is domestic. This period sounds very much-- feels a little bit more like today, where we're talking about the enemy of the people. The rhetoric back then was the enemy within this idea of subversion, of domestic subversion.

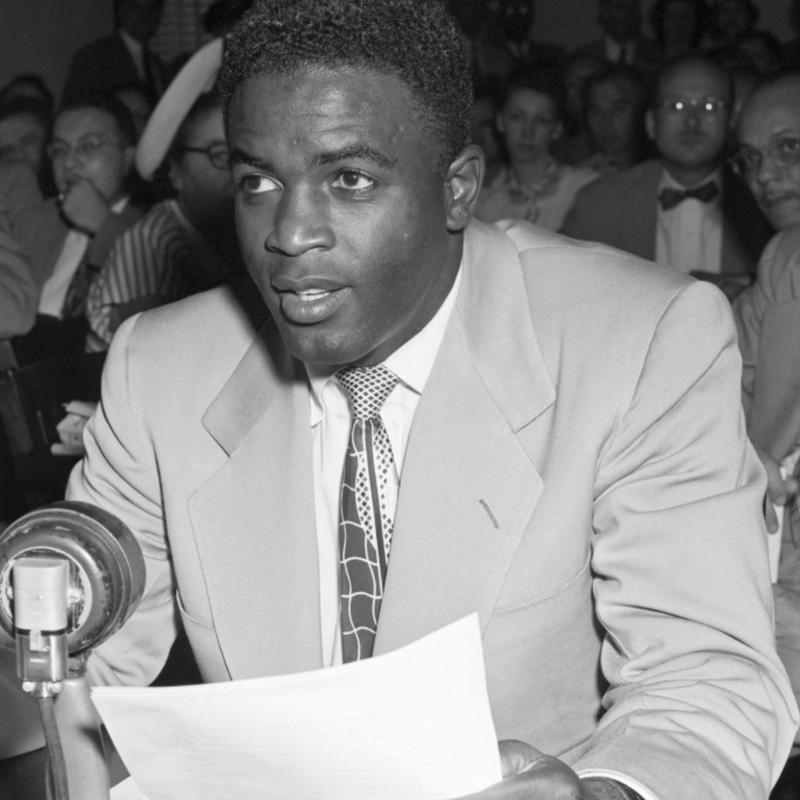

That's where the country really turned against Robeson. That's where you look at Jackie Robinson, who at that time is the most famous Black American in the country, and this beacon, supposedly, of what was possible for Black America and all Americans, even in a segregated society. The idea of taking Robeson and Robinson and placing them in front of HUAC, House Un-American Activities Committee, the most notorious government bodies ever assembled, was really the idea of pitting-- finding that one Black American to criticize the other.

Alison Stewart: It's interesting. Let's pull out for a second. What typically fell under suspicion for being unpatriotic? How did these fears ripple through African American communities?

Howard Bryant: Liberal politics, mostly. I think that we-- you feel that the attack on universities, which sounds familiar, the attack on the arts, which sounds familiar, the idea that the Soviet Union is now your enemy coming out of World War II, and when after they were allies, this idea that your citizenship is in question if you are not 100% radicalized against the Soviet Union. Whereas African Americans are concerned, one of the things that I really loved about working on this was we spend so much time talking about Black history as if it's history over in the corner. Instead, the Cold War is not Black history. The Cold War is considered American history.

Yet you have these two giants in the center of it. The real thing that brought the Black story into this is integration. It was fascinating to me working on this, how Jackie Robinson was asked to defend the United States, to defend Black loyalty, defend the virtues of this country. Then just a few years later, once you have Brown v. Board of Education, now Black people are asking for rights, now they're the ones being called communists. It's the same labeling. That was one of the things that really, really hurt Jackie. "I've done everything this country has asked me to do and now you're calling me a communist?"

Alison Stewart: Yes. He wouldn't go to games after that for years.

Howard Bryant: That's right. That was one of the real parts of the book that I was really sort of focusing on, which was, how do you have this man who once again is considered one of the-- he is one of the great symbols. Let's not forget. As much as we talk about sports, let's not forget. Baseball integrated before the military. Baseball integrated before corporate America. Baseball integrated before a lot of schools. So this is not a small thing. How can he, and he stood up and was considered by many. Many people told him not to testify in front of HUAC.

He felt an obligation to do it. He felt he had an obligation to Black America to do it. How does he, by the end of his life, feel so completely disillusioned? That was one of the things that I really wanted to get at, because we spend so much time talking about April 15th, 1947, as being this moment where everything changed. What did it do to him? What was the story? It made everybody else feel great, but what did it do to him in his day to day?

Alison Stewart: We're talking about Kings and Pawns: Jackie Robinson and Paul Robeson in America. My guest is Howard Bryant. We'll have more after a quick break. This is All Of It.

[music]

Alison Stewart: You're listening to All Of It on WNYC, I'm Alison Stewart. My guest in studio is Howard Bryant. He's written a new book called Kings and Pawns: Jackie Robinson and Paul Robeson in America, ahead of his talk tonight at 6:00 PM at the Jackie Robinson Museum. You note in your book, I'm going to read it from the book. You say, "For 73 years, the official minutes of the meeting between Paul Robeson and the owners of the 16 major league teams sat in the possession of the commissioner's office, leaving historians at the mercy of incomplete newspaper accounts offering second and third hand speculation on what was actually said within the secret halls of power."

In 2017, Major League Baseball donated the ledgers to the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum. In those letters was Paul Robeson's-- a meeting Paul Robeson had with those 16 leaders. What did he want to say to them?

Howard Bryant: It's such a wonderful-- as a researcher, you just can't wait to find something. Like, "Wait a minute, this is available?" For years these hadn't been available. So, there's this great ledger that's up in Cooperstown. You open it up and you see all the old baseball names. We've all wondered for years, what was said at that meeting? Who was there? What took place? It's so funny when you work on this title, this sort of double and triple entendre of a title, Kings and Pawns. Who's the pawn? Well, at this moment, the reason why Paul Robeson was brought to the winter meetings to meet with the baseball owners is because he's the famous Paul Robeson.

Two months earlier, he's integrated Broadway with Othello. He's the hottest man in New York. What's actually happening is the Double V Campaign the Black press has engineered, the Victory Abroad, Victory at Home campaign, which was to say we want our rights. There was nobody who was more of a target for violence than a Black person in uniform in 1943, 1944. So, the Black press is planning a protest of the Major League Baseball owners to force them to integrate, to put pressure on them.

So they bring Robeson. They bring Robeson into the meeting sort of as a flanking maneuver, not-- so, in a lot of ways, he's the one being treated as the one who's protecting baseball's interests. He gives a great speech, and he gets a standing ovation, and then by the end of the meeting, everyone wants to adjourn. One voice in the meeting says, "Are we going to address-

Alison Stewart: What he just said?

Howard Bryant: -what he just said? What took place here? This Black delegation, which had never addressed the owners before?" No one wanted to talk about it. Then this voice brought it up again. That voice is Branch Rickey. This is the president of the Brooklyn Dodgers, who eventually integrates the game with Jackie Robinson. It's the first moment where you can see that Rickey is up to something. Until those minutes were made available, we never quite knew. That was one of the other things about writing this book that I enjoyed so much, was the Branch Rickey version of the integration story is the only version that's ever been-- that we followed.

It's gone almost completely unchallenged. This was a really wonderful opportunity to talk about the complexity. The fact that New York, Brooklyn especially, hotbed of labor, hotbed of progressive politics, real hotbed of progressivism. They were the ones really forcing Branch Rickey in Brooklyn, even more so than the New York Giants, who played up in Harlem, and more than the Yankees who played in the Bronx. It was Brooklyn where the real pressure was being placed. As much as Branch Rickey, yes, wanted to integrate, because he had his moral imperatives, he was really-- he was being pressured by forces, and a lot of those forces were very much pro-Robeson.

Alison Stewart: Did Robeson and Robinson, did they interact?

Howard Bryant: That's the other piece of, is that I just couldn't believe, and I have been sweating for the last four years to find something to the contrary. How could these two giants, who were both in Harlem, they never met.

Alison Stewart: They never met.

Howard Bryant: They never met. I was stunned by this. Usually, fame meets fame. Fame always crosses paths at some point. The closest explanation was Paul's son, Paul Robeson Jr., gave an interview to ESPN years ago, where he had said he had asked his father for Jackie Robinson's autograph, and Paul Robeson refused. Because Robeson was so toxic at the time, and because the times were as dark, he said that he felt he would be making Jackie's job harder if he were to associate, to be seen with him.

By that account, it was on purpose. It was Paul Robeson protecting Jackie Robinson from any of the negative press that Robeson was getting at the time. It's stunning to me that those two had never met.

Alison Stewart: Why was Robeson "toxic" at the time?

Howard Bryant: Because of his progressive politics. Because of his associations with the Communist Party, because he was not going to back down from those politics, or from those associations, and also because he was at odds with the Black establishment. With the Urban League and the NAACP, that really wanted to be the only voice when it came to civil rights. Robeson and W.E.B. Du Bois were on their own. Robeson, in 1946, met with President Truman to stop the lynching of Black soldiers. Truman essentially told him, "Well, it's not really a good political time."

You're dealing with a real forceful character here. In addition to his international politics, he's also an extremely powerful voice domestically. That really, in a lot of ways, put him at odds with a lot of the Black leadership who felt that you can't conflate the two. That our allies, if we are associated with communism, if we are associated at all with the Soviet Union, the allies that we have for civil rights are going to abandon us. A lot of the Black leadership turned on him by saying, "Listen, you are hurting our movement by essentially being a pawn of the Soviet Union." So, it's really fascinating.

Alison Stewart: He didn't care, though. He gave a speech and-

Howard Bryant: Gave a speech and didn't care.

Alison Stewart: -didn't care.

Howard Bryant: Yes. What I loved about it was that this is a story of tactics. Of course, then you have Malcolm X years later, who comes in and says, "No, the real pawn, and this was the Black establishment. Looking for a love and looking for a respect from people who were never going to give it to you."

Alison Stewart: Let's talk about the 1949 hearing. Why was Jackie Robinson asked to testify at this time in front of HUAC?

Howard Bryant: Because Paul Robeson's voice was just too big.

Alison Stewart: It was too big?

Howard Bryant: Enormous. Well, he gives a speech in Paris, and he's misquoted by the Associated Press. What comes across to the United States on April 20th, 1949, was Robeson being quoted as saying, "It's unthinkable that the Negro people would fight against the Soviet Union in the event of a conflict, in the event of a war between the two." So, the right-wing forces here, the House Un-American Activities Committee, immediately, they're like, "That voice needs to be parried. Whose voice could actually match the same-- who's got the same stature of a Paul Robeson?" It was Jackie Robinson. Of course, it had to be somebody Black. So, at that-

Alison Stewart: So cynical.

Howard Bryant: So cynical. At that-- but once again, and we say the same thing today. I've been saying this. The Black person who's willing to criticize another Black person publicly will have a job for life. He's set up for this. Right? Here's the thing about Jackie. As much-- and people implored him not to do this. Said HUAC was-- they were bad people. It's really, the Un-American Activities Committee, it's not-- you don't want to be associated with these folks. He felt implored to do it. He felt a loyalty to Branch Rickey, who really is the one who put him up to it.

He would later say in his memoirs that he felt that if white people believed that Blacks were disloyal, then we would lose our support and it would set the movement back. So he felt an obligation. Here's the thing about Jackie Robinson in 1949. It's four years after Branch Rickey has signed him, and his own sport, baseball, has really not integrated. He's all by himself, and he's supposed to be this beacon. Yet, on opening day 1949, there are seven Black players in the league, and five of them play for either the Brooklyn Dodgers or the Cleveland Indians.

So, he's disillusioned that there's no progress. "You brought me here. I'm supposed to be the first of many, and yet here I am by myself." So, you can start to see his own disillusionment as well. By the time he retires, after the 1956 season, three baseball teams still haven't integrated. The Detroit Tigers, the Philadelphia Phillies, and the Boston Red Sox.

Alison Stewart: Never mind any Black managers.

Howard Bryant: Black managers would come three years after he died.

Alison Stewart: What happened in those days after he testified?

Howard Bryant: Well, one thing that has been very, very clear, is that Jackie Robinson did not destroy Paul Robeson's career. Paul Robeson's career was already on the downside the previous years. I mean, he'd lost a lot of concert dates. What Jackie's testimony did do was it unleashed the forces. The negative forces that were already against him felt very much emboldened now. Especially because you had another Black person and you had the NAACP also abandoning Robeson, now it was sort of open season. Now it wasn't a racial thing. It was like, even the Black leadership is not going to defend him. So he was isolated.

What that did, five weeks, five and a half weeks after Jackie's testimony, you have two infamous bloody riots in Peekskill, New York. Then within a few months after that, the United States government refuses to issue Robeson a passport. So, they hold his passport. They essentially have him under house arrest for almost a decade.

Alison Stewart: As we wrap up here, what are the similarities in how you see Black American athletes and entertainers navigating careers and their political stances today?

Howard Bryant: It's very similar, I feel. It's really interesting, too, in 2026, because this is going to be the 10th anniversary of Muhammad Ali's death, who sounded very similar to what Paul Robeson was saying in the 1940s. It's a continuum. This idea, once again, that the African American athlete has to take on this responsibility. The entertainer, the artist has to take on this responsibility. It's the same continuum. It's going to be the 10th anniversary this year of Colin Kaepernick taking a knee in August. So, what is past is prologue.

Alison Stewart: As you're saying that, I'm also thinking to myself, I'm thinking of, "Well, it's Bad Bunny now-

Howard Bryant: Exactly.

Alison Stewart: -who's got to take that role." There's also other artists who are Latino who have to take that role currently.

Howard Bryant: Well, that's right. Everyone's watching. The hard part is, and I listen to what Malcolm X would say, is he would say, "This is not our role." He would refer to these athletes and these entertainers as puppets, because it's so hard to be able to be asked to do something that is maybe beyond your skill set, but wasn't beyond Paul Robeson's. He could do anything.

Alison Stewart: The name of the book is, Kings and Pawns: Jackie Robinson and Paul Robeson in America. It is by Howard Bryant. He will have a talk tonight at 6:00 PM at the Jackie Robinson Museum. Thanks for coming in.

Howard Bryant: No, it's my pleasure. Thank you.

Alison Stewart: Coming up, we'll continue our Full Bio conversation with Amanda Vaill, the author of Pride and Pleasure: The Schuyler Sisters in the Age of Revolution. Today's sister, Angelica. She was intellectual, fiercely independent, and unafraid to marry a man who her father disapproved of. That's next, right after the break.