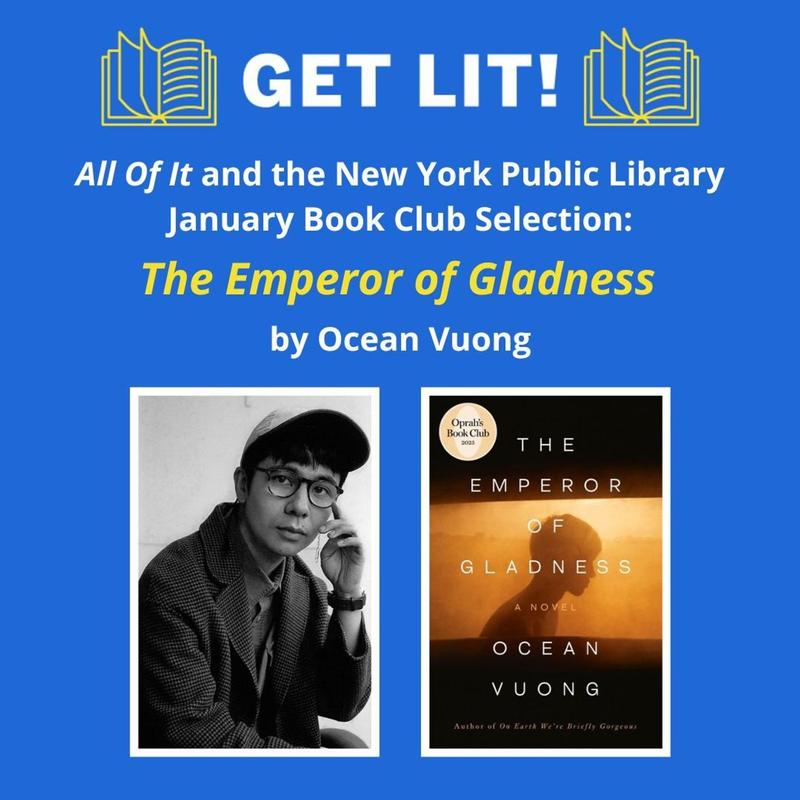

Get Lit Preview: Ocean Vuong on 'The Emperor of Gladness'

Alison Stewart: You are listening to WNYC. I'm Alison Stewart. It's a new year, and that means it's time for a new Get Lit with All Of It Book Club selection. We are kicking off the new season by reading The Emperor of Gladness by Ocean Vuong. It was named one of the best books of 2025 by the New Yorker, NPR, Kirkus Reviews, and more. The story follows Hai, a young man struggling in a small post-industrial town of East Gladness, Connecticut. Hai has dropped out of college, but he hasn't told his mom. She actually thinks he's going to medical school. Hai has addiction issues and finds himself feeling hopeless.

One day, he considers taking his own life while on a bridge, but before he can do it, he is spotted by an elderly woman named Grazina. Grazina offers to let Hai stay at her house, where he learns that she's struggling with dementia. He becomes her caretaker, but he has to have a job as well, one he finds at a fast casual restaurant full of people with hopes and dreams. Thanks to our partners at the New York Public Library.

You can borrow an e-copy of the novel, and you can get free tickets to our January 20th Get Lit with All Of It Book Club event at the Stavros Niarchos Foundation Library. Head to wnyc.org/getlit to find out how. Now here's a preview of the book to get you a little excited to start reading. This is a bit of my conversation with Ocean Vuong last year. I began by asking what events brought Hai to the bridge the night he decides to take his own life?

Ocean Vuong: I think often we think people who are at the end of the line need to have a grand reason, but when my own uncle took his own life in 2012, he was 28. I was 24. He was like a brother to me. We grew up in this country. We were in the refugee camps together. In his letter, I'll just paraphrase it, he said something to the extent of, "I just had enough of it," as if he was pushing something away. That really struck me because we often believe there should be a dramatic reason, that this is not enough, but sometimes we lose steam.

For me, I wanted this character to also arrive when things run out of options rather than some sort of absolute sadness. We often see the suicide as a kind of triumph when they step off the bridge, and, God willing, they do, but I'm interested in what happens on day 2, day 3, day 20, a question that I never really got to ask my uncle, because that's a really vexed place to have no hope and yet decide to live. How do you go forward? That, to me, is a wonderful place to start a fiction project.

Alison Stewart: Fortunately, he has Grazina, this older woman in his life. How would you describe her?

Ocean Vuong: A survivor, a quintessential American, having fled Stalin in World War II and arrived in America in the '40s and '50s and tried to make a life. Then, meeting Hai, who survived the Vietnam War. To me, America is a layered place of war. These folks are ejected from geopolitical ruptures, and yet they find each other in the same room. They realize that their histories are not so far apart. Unlike the white picket fence or the grand city on the hill, to me, America's most promising moment for itself is recognizing that it is a history of war. From those wars, it is also a history of life and life building.

Alison Stewart: This character of Grazina is based on a real woman that you knew. You spent some time with her. Who was the real woman, and what was your relationship like?

Ocean Vuong: Grazina Verselis was an incredible person who I lived with while I was studying at Brooklyn College. I lived with her in Richmond Hill, and I was her caretaker. She was a friend of mine's grandmother, and that was how I made it through college. I lost my housing when I dropped out of Pace University. When I signed up to Brooklyn College to study English, I still didn't have a means or a place to stay. She took me in, essentially, and I tended to her needs, experiencing frontal lobe dementia.

I didn't know what it was. I remember googling WebMD what dementia was. To me, I had to follow her. I had no right, with all of my faculties, to demand or correct her. Living with someone with chronic mental illness, you have to follow their reality. It became actually a really foundational lesson in fiction to me because I realized that she was inventing and remembering all at once. So much of my own work is about memory and invention at the same time. Who am I to say that her reality was any less real than mine? I would follow her fictive propulsions, and I would have to make up the world alongside her.

Alison Stewart: Would you read a bit from your book for us? I think this section sets up where Hai is in his life when we meet him.

Ocean Vuong: Yes. "When he was younger, Hai wanted a bigger life. Instead, he got the life that won't let him go. He was born in Vietnam, 14 years after the big war everyone loved talking about, but no one understood, least of all himself. The year was 1989, a year best known for the fall of the Berlin Wall and the Tiananmen Square protests. George Bush Senior had defeated Michael Dukakis to be the 41st president, and My Prerogative by Bobby Brown was at the top of the charts. It was the time of the floppy disk, denim jackets, leg warmers, Cool Ranch Doritos, and pasta salad.

In Vietnam, the Americans had left the fields a ruinous wasteland with Monsanto-powered Agent Orange, not to mention the 2 million bodies, nameless and scattered in the jungle and riverbanks, waiting to be salvaged by family members hoisting woven baskets on their waists full of sun-bleached bones. On top of that, the country was fighting the genocidal Pol Pot and his Khmer Rouge, who were invading the Western border. People starved naturally and scavenged for rats or stretched their rice rations with sawdust from the lumber yards.

Two years later, by miracle or mercy, Hai and his family arrived in snow-dusted Connecticut. Their faces blasted and stricken, sleeping their first weeks on the floor of the Catholic church that sponsored them between the pews, using Bibles for pillows. He was only two and remembered none of it. He was raised by his mother, grandmother, rest her soul, and Aunt Kim, women spared by war in body but not in mind, and together they found a way to scavenge a life in wind-blasted Hartford.

Though he had his troubles, the boy couldn't say he had a bad life. After high school, he got into college, the first in his family to do so, enrolling at Pace University in New York at the foot of the Brooklyn Bridge. Although he intended to study international marketing, at the last minute, for reasons unknown to him, he switched to something called General Ed, which sounded more like the abandoned wing of a psych ward than a degree. By then, he was already going steady for half a decade with the pills and spent most days in the library's basement, nodding off and reading literary periodicals and giant photography books.

He once spent two hours out of his mind on a mix of cough syrup and oxy, staring at the Diane Arbus photo of the little boy clutching a grenade in Central Park. By Thanksgiving, he was out of school and back in East Gladness, slumped on his mother's couch. New York City, all but a faded dream. Even now, he did not understand the chain of events that led him back to this dirty old town empty-handed."

Alison Stewart: There's Ocean Vuong, reading from his new novel titled The Emperor of Gladness. There's so much to talk about in there. His addiction. At some point, he decides that this works for him. What do the drugs provide him?

Ocean Vuong: They provide a coping mechanism to the idea of dashed hopes and dreams, which is what I'm deeply interested in as a novelist. So much of our history and our culture is obsessed with grand moments of revolution, fighting back, twists of fate, overthrowing bosses, overthrowing wars, and tyrants. The history book marks those. A lot of fiction and movies come out of those grand moments.

When I look at the archive, I actually realize that a lot of history is filled with people who can't escape, who can't get out. Stuck in the coal mines, stuck in the factory, stuck in marriages that perhaps they didn't even want to have, that they couldn't break out, they couldn't follow their dreams. That actually is deeply interesting to me because the question then for the writer is, what is the point if the plot does not lead you to escape? To me, the point is people. I'm more interested in people trying their best. This is not a healing narrative.

I knew when I wrote this book that the protagonist would not kick his habit. People won't get a raise, they won't get out of town. It's not going to be rags to riches. Instead, it is people as they are, and they transform. They do, but without change. That's deeply important to me because so much of American life is static, but it does not mean that it is doomed.

Alison Stewart: It's interesting, it just reminded me of something an elder, an ancestor, told me once, a Black ancestor, who told me, "Well, when we were really, really young, we couldn't plan. We didn't have the facility to plan. It had planned out where we would live, where we would go to school." I found that to be interesting. I heard that a little bit in what your answer was.

Ocean Vuong: Absolutely. That's such a luminous idea because I think, why did I end up in Hartford? It's not exactly the narrative that is known for having Vietnamese American life. Many Vietnamese Americans, as soon as they got to the East Coast, went to Houston, LA, Orange County, Minnesota, even Iowa, but Hartford, for me, for my family, was a place where we could rest because so much of our life was out of our hands. We couldn't plan where we were headed. We couldn't plan where we were going to be.

When they got to Hartford, they looked at each other and said, "You know what? We're tired." You know who picked us up and who showed us where we were and where we were heading towards, was the Black and Brown community in Hartford, Connecticut, the Dominican immigrants, Haitian, Jamaican immigrants who came to Hartford to work the tobacco fields when agricultural workers were sparse during World War II. We were taken into the Baptist church, given free food. I think what I realized was that the Black community in Hartford knew we were heading into America that we had to quickly understand in order to survive.

Through physical gestures of generosity, they, in a way, metaphorically and physically sat us down and said, "Listen, you got to know what this is if you're going to make it." They saw the precarity, I think, of our situation more clearly than we ever did, because when we got into that first one-bedroom apartment, seven of us, I remember very distinctly my grandmother coming to the window and she's showing me. She said, "Look, the windows open and close with locks. We did it. There's glass. Look how sturdy."

Mind you, we were in a refugee camp with a tin roof two months prior. There was this hallucinatory power of being absolutely privileged, and yet in an incredibly precarious economic world of new American life. It was the Black and Brown community of Hartford that really taught me what America truly was.

Alison Stewart: That was part of my conversation with author Ocean Vuong about his new novel, The Emperor of Gladness. It's our January Get Lit with All Of It Book Club selection. To borrow your e-copy courtesy of the New York Public Library, and to grab your free tickets to the January 20th event, head to wnyc.org/getlit.