Full Bio: The Early Life of Senator Charles Sumner

( Photo by: Universal History Archive/Universal Images Group via Getty Images )

Alison Stewart: This is All of It on WNYC. I'm Alison Stewart. We just talked about ice cream, so it's time to remind you of another summer tradition, the annual All of It Summer Reading Challenge. We're asking you to read at least one book in all of the five following categories. They are a classic you've been meaning to get to, a book about or set in New York City, a memoir or biography, a recent debut novel, or a book published in 2025.

Head to wnyc.org/summerreading to register and to download the Summer Reading Challenge PDF. Again, that's wnyc.org/summerreading. Once you've completed the challenge, we'll follow up about your selections to receive a prize, and happy reading. That is the plan. Let's get this hour started with something that fulfills one of those categories. It's this month's Full Bio Conversation.

[music]

Full Bio-- Settle down. Full Bio is our book series where we spend a few days with the author of a deeply-researched biography to get a fuller understanding of the subject. Today we'll discuss the book Charles Sumner: Conscience of a Nation by Zaakir Tameez. Born in 1811, Senator Charles Sumner was a prominent abolitionist and leader for integration. Now, there have been several other bios of Sumner, but this one we're going to talk about has an interesting twist. Its author, Tameez, was recently a graduate from Yale Law School, and He's in his 20s. He's taken a new look at Sumner and what he stood for in this 533 page book.

As the New York Times reported, until last year, there hadn't been a study of Sumner in four decades, and almost none with his impact on this nation. Charles Sumner was a man who was the grandson of a revolutionary fighter, the first librarian of Harvard Law School, a senator from Massachusetts, and he was at President Lincoln's bedside when he died. He was a brilliant legal mind, which the book gets into.

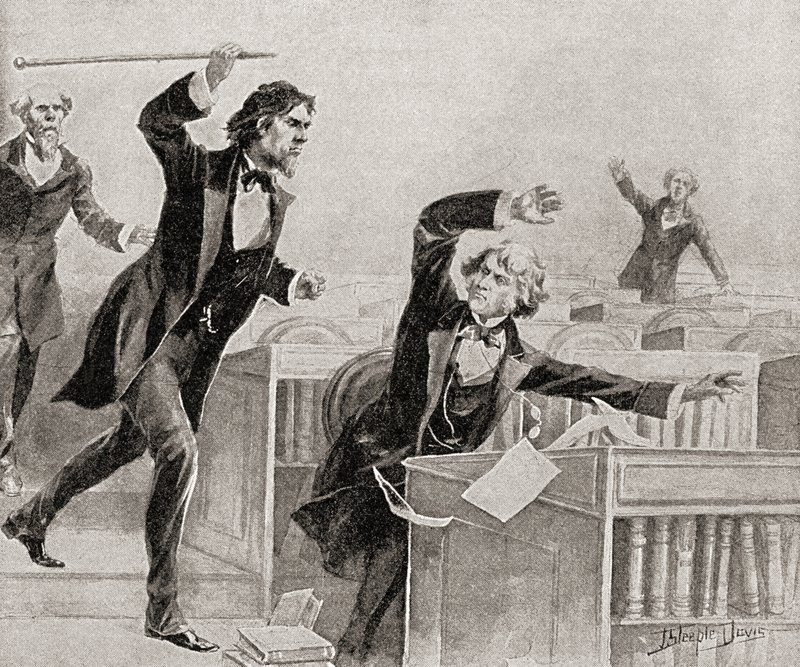

Sumner argued that, "The Constitution is not mean, stingy, or pettifogging, but open handed, liberal and just, including always in favor of freedom." He used his position to help the country see that slavery was wrong and would destroy the country. It almost assured him. Sumner, of course, was nearly beaten to death on the Senate floor for his anti slavery views. The book uses 600 of Sumner's personal and professional letters, 400 contemporaneous newspaper articles, and the works of the men who influenced him growing up, which is where we will start, with his family tree, which dates back to the American Revolution.

[music]

I think before talking About Charles Sumner, it's important to understand his ancestry, which dates back to the Revolutionary War. His paternal grandfather was named Job Sumner. What role did Job play in the American Revolution?

Zaakir Tameez: Job Sumner was the child of farmers in rural Massachusetts. He descended from one of the first generations of Americans to come to this soil in the 1600s. He decided to go to Harvard University in his mid teens. Right after he gets there, ironically, the American Revolution begins in the farming town that he had left. Next thing you know, colonists are fighting British redcoats at Lexington and Concord.

Job Sumner was itching to get involved in the fight, but the fight came to him when revolutionaries arrived at Harvard University's campus and demanded to take over the college campus to set up a military encampment in Cambridge in order to try to take Boston, which was in British possession. At that moment, Harvard asked the student body to leave campus and to continue their studies in the countryside, but Job Sumner said no.

Instead, he stayed at Harvard and joined the Revolution. Within just a few years, this farming boy rises the ranks of the Revolutionary Army. By 1783, he is a leading major who helps to supervise the evacuation of the British from New York City, escorts George Washington into the city to liberate New York, and becomes one of the leading revolutionaries.

Alison Stewart: It's really interesting, because one of our listeners, we had a segment on Fraunces Tavern, and that he was there. Job was there to help George Washington celebrate the end of the war. I'm curious, what did he do with himself after the war?

Zaakir Tameez: That's right. Job Sumner was there with Washington at Fraunces Tavern when Washington is kissing goodbye to the officers. Then Job Sumner afterwards gets an appointment to be a commissioner in Georgia. Here is what is really striking. Job Sumner, this revolutionary who fought for freedom, goes to Georgia, hobnobs with Southern planters, and becomes a slaveholder. Unbeknownst to Washington, or probably to anyone in the Revolutionary Army, Job Sumner had a son, which was Charles Sumner's father, Charles Pinckney Sumner.

Job Sumner impregnated a farm girl in Massachusetts around the same time of the Battle of Lexington and Concord. He did not marry this woman. He has this bastard son in rural Massachusetts who is literally toiling to survive, who is herding cows late at night, who doesn't have much of an education at first, while Job Sumner is enjoying a prestigious life as a Southern planter.

Alison Stewart: It's interesting, the girl that he impregnated named him Job Junior, but he didn't take too Kindly to that, gave him the name Charles Pinckney Sumner. Why Charles Pinckney?

Zaakir Tameez: Charles Pinckney was a founding father from the south who was extremely pro-slavery, who was probably one of the most pro-slavery founding fathers. For Job Sumner, it was an honor to name his son after this man. Yet Charles Pinckney Sumner grows up deeply resentful of his father, understandably so. When his father ultimately dies, he gets some money and enrolls himself at Harvard College. While there, he becomes an abolitionist, probably as a way to reject his father's contradictory ideals of being both a revolutionary and being a slaveholder.

Charles Pinckney Sumner would go on, after graduating from Harvard, to become a sailor, a sailor who traveled on a ship that stopped in Haiti during the Haitian Revolution. While he's there, General Jean-Pierre Boyer, one of the leading Haitian revolutionaries, organizes a birthday party to celebrate George Washington's birthday. This white boy from Massachusetts, son of the American Revolution, joins this celebration in Haiti, and actually lifts his glass and gives a toast to liberty, freedom, and equality for all men. General Boyer is so shocked to see this white American celebrating the Haitian cause, and invites him to the front, where he stays for the rest of the night.

I think this combination of Charles Pinckney Sumner celebrating the Haitian Revolution, and his father, Job Sumner celebrating the American Revolution, probably informed the grandson Charles Sumner's upbringing and ideology.

Alison Stewart: My guest is author Zaakir Tameez. We're discussing his book, Charles Sumner: Conscience of a Nation. It's our choice for Full Bio. Charles Pinckney Sumner marries a woman named Relief Jacobs, I love that name, and the subject of your bio. Charles Sumner is born. He's a twin of Matilda. He's the eldest of, I believe, eight children. What kind of child was Charles Sumner?

Zaakir Tameez: Charles Sumner was a fascinating kid. He is very scrawny. He looked sickly. He didn't engage or enjoy physical activity. He didn't go swimming with his siblings. He was not interested in dance class. He just loved to learn. While he's young, he decided that he wanted to learn Latin, and he wanted to go to the Boston Latin School. Now, the Sumners didn't have much money, and Charles Sumner decides to borrow money from an older classmate to give him a Latin textbook.

He comes down the stairs one day, confronts his father while his dad is shaving, and starts to speak in Latin. He's like nine years old at this moment. That was his way of persuading his parents to give him an opportunity to take the entrance exam to the Boston Latin School. He's accepted, and next thing you know, this scrawny kid is starting to learn the classics, something that he would enjoy for the rest of his life.

Alison Stewart: He grew up in a neighborhood where Black Bostonians lived, the Black Beacon Hill area. Tell us a little bit about the people that live there, and how do you think that shaped Sumner's feelings about race early on?

Zaakir Tameez: Sumner grows up in a contradiction. On the one hand, he is a third generation Harvard educated man-- or he grows up and becomes a Harvard educated man. On the other hand, he is living in this ethnic enclave of Boston that has a large free Black community, because his family did not have any money to live anywhere else. That experience gave him a deep sense of empathy and sympathy for his Black neighbors.

Black Boston at this time is a small community of extremely persecuted and marginalized people, but there are also a number of artists, of writers, musicians. Free Black Boston, around a thousand people, was, in many ways, the cultural capital of Black America in the early 1800s. Only a few blocks from Charles Sumner's home was the African Meeting House, one of the first Black churches in the country, still standing today.

There was also a Black Masonic lodge, the first of its kind. There was the African Mutual Aid Society, an organization of free Blacks that would try to give money to protect their own community. Sumner saw Black schoolchildren going to the Smith School, one of the earliest Black schools in the country. There were writers in the community like David Walker, a famous Black abolitionist, who wrote a tract that called out white Americans for their hypocrisy in celebrating the Revolution and the Declaration of Independence, but not granting that freedom and equality to their Black neighbors.

Alison Stewart: How was Sumner viewed by his neighbors, by his Black neighbors?

Zaakir Tameez: Sumner's father was an abolitionist, and not only that, he believed in racial equality. He was known to not use the word Negro, and he preferred calling his neighbors people of color, a term that we think is a modern term, but actually has been around for more than 200 years. In addition, he was known to tip his hat whenever walking past an African American on the street.

He once said that he was waiting for the day that there would be Black judges in Boston. The Sumners were a white family that was respected, and honored, and considered a peer by their Black family neighbors. Sumner had this upbringing that taught him to treat everyone as equal, and that also gave him a window into the daily brunt of oppression that this community faced every day.

Alison Stewart: You're listening to Full Bio. We're discussing Charles Sumner: Conscience of a Nation. My guest is Zaakir Tameez. What was Charles Sumner's experience while at Harvard and Harvard Law School?

Zaakir Tameez: When Sumner gets to Harvard, he is so excited. Then he discovers how difficult and tedious the curriculum was at the time. He complained about the food, he complained about his peers. Most of all, he complained about his teachers who just wanted him to memorize, memorize, and memorize. That changes when he finally gets to Harvard Law School. Now, this "law school" barely existed at the time. It was really just a small group of students and one teacher named Joseph Story.

Joseph Story was a titan of American law. He was a justice on the US Supreme Court. He was, in many, ways a lieutenant to Chief Justice John Marshall. Story pretty much founds the school, and Sumner is one of his first students. Story comes up with a new curriculum for teaching law. He decides to have his students read before class, and then, in class, he would call on them to explain the reading. For anyone who has been to law school [unintelligible 00:15:24]. It's called the cold call. Story had invented it, and Sumner is one of the first students to ever be cold called in history.

He was good at it. Story very quickly realizes that Sumner is a kind of prodigy. He starts to invite Sumner to his home, where Sumner would just riddle Story with questions about this topic and that topic. Story asks Sumner to be his research assistant, and to find cases for him to edit some of his treatises. Story's son, William, would go on to say that his father treated Sumner like a son, which I'm sure made for an interesting dynamic, because Story had a son. Story's son, William, goes on to become an artist. Sumner becomes the lawyer and the jurist that Story wanted for his own child.

Alison Stewart: Story believed in equity jurisprudence. First of all, please explain what that means, and how did that impact Sumner's opinion of the Constitution? This becomes very, very important, as we will discuss later.

Zaakir Tameez: Historically in English common law, courts were only able to grant remedies in the form of monetary compensation. That changed sometime in, I want to say, the 1500, 1600s, when the English kings invented a new system of courts called the courts of equity. Equity courts were able to do all kinds of fashionable remedies. They could issue injunctions which would order a party to do something. Your compensation as an injured party might not be money, but it might be an order from a court.

Equity jurisprudence is really important to Sumner's early training in the law, because Story was a proponent of equity. The logic of equity is that sometimes a court needs to be creative about how to right a wrong, that courts need to come up with new ideas and new strategies to address the violation of rights, even if there is no remedy on the books or there is no monetary remedy in law. Story trained Sumner to have a deep respect for equity jurisprudence, which is something that Sumner takes with him for the rest of his life in trying to think creatively about how law can right wrongs, even when, historically, there was no right to the wrong.

Alison Stewart: It's interesting. Initially, though, he didn't do well as an attorney. You write in the book, "Sumner's legal career would fail to take off and achieve the high expectations everybody placed on him." First of all, what were the expectations of him, of Sumner?

Zaakir Tameez: When Sumner graduates from law school, he first becomes the librarian for Harvard Law School, the first librarian ever of the school who actually published his first catalog. Then he practices law briefly, but he tells his mentors that he wants to go to Europe. His mentors are very nervous about this. One mentor, Josiah Quincy, the president of Harvard, says, "You will go and get a cane and a mustache and additional stock of vanity." [chuckles] [unintelligible 00:19:13] Another mentor, Simon Greenleaf, writes to him and says, "To see through all the Jacobinism, radicalism, and atheism of modern Europe, and all the other isms, and come back to be the good conservative that God made you."

There is enormous pressure from his mentors for him to be a conservative lawyer, for him to be an attorney representing the Boston merchant class, rather than getting involved in any kind of human rights activism. To please these mentors who trained him, who taught him, who took care of him, he does exactly what they tell him to do. After returning from Europe, he becomes a corporate lawyer in Boston.

He represents Boston merchants, but he is not enjoying this at all. While he does well, at first, his client list quickly dwindles down, probably because they recognize he had no enthusiasm for his practice. Next thing you know, he's barely practicing law, even though he is one of the most educated lawyers in the continent. He had a nickname, the briefless barrister, because he was so smart and so talented, but had no cases. Very quickly, his legal career flounders.

Alison Stewart: One of the things about him traveling to Europe, Charles Sumner traveling to Europe, is-- I think you said it in a really interesting way, it set the intellectual tone for the rest of his life. What's an example of something he saw or an experience he's had that changed his mind about what the United States could be?

Zaakir Tameez: I'll give you two examples. When Charles Sumner arrives in Europe, he first goes to Paris. He is just shocked at how terrible his French is. Even though he had studied French in school, he couldn't hold a conversation with the Frenchman. He decides, rather than go see all the sights, go visit the chateaus, go explore the countryside, or do whatever one does in Paris, he is going to go to university lectures and learn French.

He told one of his professors, "I'm not even sure I believe this." He said in a letter that he attended more than 150 lectures in French in Paris. As he's going to these different universities, including the Sorbonne, he sees white and Black students sitting side by side, learning philosophy, learning history, learning literature. He is startled by this sight, because in his own country, even in Boston, where he lives in a Black community, it was inconceivable to imagine Black and white students learning together.

At the same time, he is also meeting a number of French aristocrats. Many of these aristocrats were totally ignorant of the United States. They didn't care for it. He was shocked to meet one aristocrat who was extremely well-educated, but who asked him, with a serious question, which was, "Do you Americans speak the same language as Montezuma?" In other words, do you speak Aztec? He is startled by this level of ignorance from an educated man, which I think may resonate with many immigrants to America today who might meet someone educated who asks a really dumb question about where they're from.

Sumner realizes that America is more or less a backwater considered by Europe. Then he realizes that if educated Frenchmen knew anything about America, the thing they knew was slavery. By this time, Europe had abolished slavery in most countries. It still existed in the colonies, but continental Europe had very little slavery, at least in Western Europe. Europeans are just disturbed by the existence of chattel slavery in America.

They're also disturbed by the racism in America. Charles Sumner realizes that, "My God, my country will never be respected on the world stage until we address the question of slavery and racism." He also realized that another world was possible, a world in which whites and Blacks were equal, were learning together, were governing together, as he was seeing at these university lectures in Paris.

Alison Stewart: When Charles Sumner returned to Boston, what were some of the earliest causes that he showed interest in?

Zaakir Tameez: He took an interest in a variety of causes, much of which revolved around education. He became close to Horace Mann, often considered the father of American public education. He ran for school board unsuccessfully. He tried to campaign to create a teachers college that would teach teachers to become better educators for the next generation. In fact, when it wasn't going well, he decided to pledge his own money to building this teacher's school, and then to collect money from donors later to compensate himself. The whole thing fell apart. He realized the donors who were promising money weren't actually going to give it. That was a hard lesson for him, which is that when you're trying to do good in the world, you will often have people who are saying the right things, who are encouraging you down the road, but they themselves are not willing to reach into their pocketbooks and contribute, or not willing to give their time, or to risk anything. Sumner learns, at that time, how difficult it is to pursue reform, and yet he has this deep passion for it, and he continues to give it his best.

Alison Stewart: That was Zaakir Tameez, author of Charles Sumner: Conscience of a Nation. Tomorrow, we'll learn about what led to his caning on the Senate floor, and why the author believes that Charles Sumner was gay.