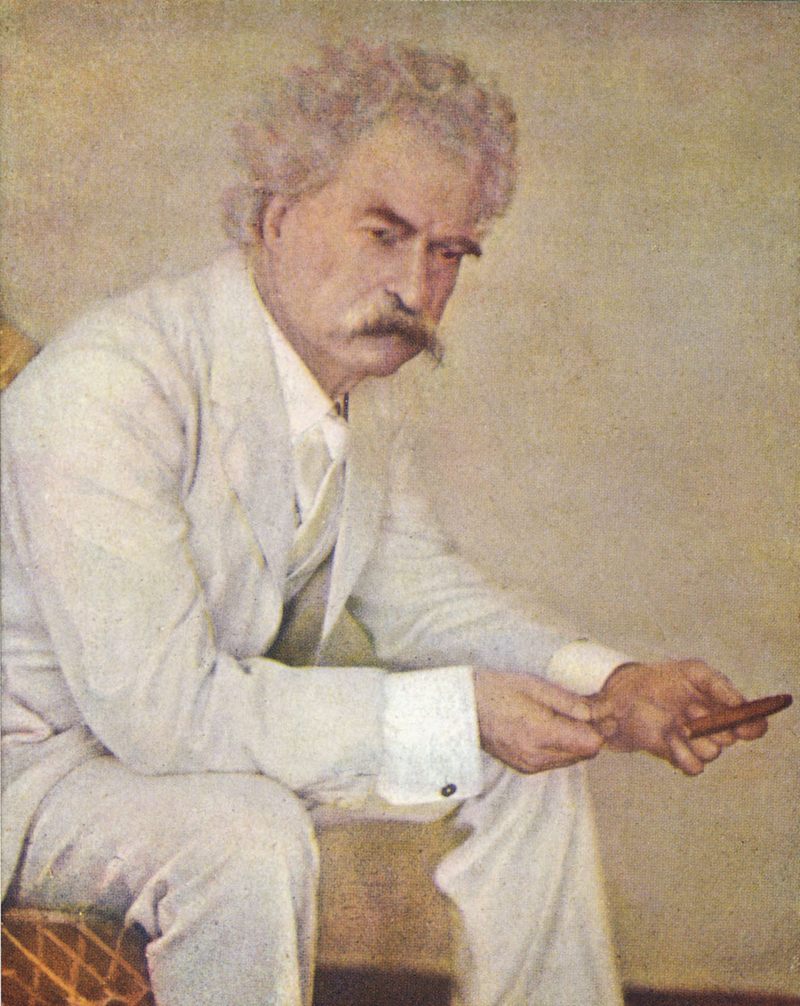

Full Bio: Ron Chernow on the Big Issues that Dominated Mark Twain's Life

( Photo by Culture Club/Getty Images )

Alison Stewart: This is All Of It from WNYC. I'm Alison Stewart. Coming up on tomorrow's show, we've got Jasmine Amy Rogers, the star of Boop, the musical on Broadway. She's having a big week over the weekend. She won the Drama Desk Award for outstanding lead performance in a musical. She's also nominated for a Tony for best actress at this Sunday's award show. Now there's a petition to have her perform there, too. Nearly 5,000 people have signed it. That's a lot of hype for a 26-year-old actress in her Broadway debut. She'll be with us tomorrow to talk about stepping into the role of the iconic Betty Boop. That's in the future.

Now, let's get back into today's show with this month's Full Bio conversation. Full Bio is our monthly book series where we spend a few days with the author of a deeply researched biography to get a fuller understanding of the subject. This month, we are discussing Mark Twain by Ron Chernow. Chernow has written biographies of Alexander Hamilton, President Ulysses S. Grant, and won the Pulitzer for his book Washington: A Life about our first president.

As we learned yesterday, Mark Twain was born Samuel Clemens in 1835 in Missouri. He was one of seven children born to an outgoing mother and a father who died when Samuel was 11 years old. He worked as a printer's apprentice, on a steamboat, but found his way as a writer and a speaker. Today, we'll learn about Mark Twain, a man of extremes. As he said, everyone is a moon and has a dark side which he never shows to anybody. Mark Twain could be as vengeful as he was kind.

He was in the 1%, but lost it all due to an obsession he had with an invention. He lost millions and millions of dollars, much of it his wife's inheritance. He went through an evolution on racism. Mark Twain called himself "a bigot as a young man," but ended up writing an anti-slavery novel, but full of the N word. All of this was documented in his writings and letters, and there may be some coarse language in this episode which was lightly edited. Let's get into the mind of Mark Twain with Ron Chernow. When did he become Mark Twain?

Ron Chernow: Well, when he was writing in Nevada, it was the habit of a lot of the journalists and a lot of the humorists to adopt pen names. It was at that point that he went from being Sam Clemens to Mark Twain. He went back to his steamboat days for that name because Mark Twain means two fathoms, or at 12ft. On the steamboat, they would drop a lead anchor there in order to gauge the depth of the river. If the leadsman cried Mark Twain, it meant that the depth was 12ft at that point. That's where the name came from. It was a wonderful choice of name.

In fact, he became very good friends with Helen Keller. Helen Keller told him that she thought it was a perfect name because the nautical significance, it gave a sense of beauty, but also of depth that called to mind the river, which was exactly perfect for him.

Alison Stewart: Which of his works do you think people should pay more attention to?

Ron Chernow: More attention to? I think the first book, which is called Innocence Abroad. It was actually his best-selling book in his lifetime. What happened was he went on this-- It was like an early tourist cruise to Europe and the Holy Land. He went with all of these rather stodgy, pious American tourists. He wrote all these letters. Then it became this book, the Innocence Abroad. He's not only satirizing what he sees in Europe, but he's satirizing his fellow passengers.

At that time, people would do the Grand Tour of Europe because Americans would fawn over European culture. Mark Twain was having none of that. For instance, they were going to a lot of museums, and he developed this pathological hatred of the Old Masters. He said, "The Old Masters are all dead, and I wish they had died sooner."

They go to the Sistine Chapel where the Conclave just met. He said, "Michelangelo's Nightmare," he said, "full of repulsive monstrosities." He then goes to Milan and he sees da Vinci's The Last Supper. He said that there were a dozen people copying The Last Supper in the room there. He said, "I couldn't help but notice that all of the copies were much better than the original." [laughs] Then this very, very funny statement, he said, "There are a lot of house painters in Arkansas who wouldn't be painting signs for a living if they had lived in the days of the Old Masters.

Anyway, this was such a breath of fresh air at the time when everyone was sort of fawning over European culture. Here was this fresh voice that was so bright and brash and cynical. He had no filter. There wasn't any sense of political correctness at the time. Anything he could satirize and get away with, because he makes all these comments about different races, and religions, and nationalities. He has a kind of harsh wisecrack for everyone, but at the time, that was okay.

By the time he gets back to the United States after months on the Quaker City, because he's been filing these letters, he returns a celebrity. The book sells 100,000 copies, a gigantic amount at the time. He never again sold as many copies, and that drove him crazy.

Alison Stewart: Ooh. I'm going to call him from Mark Twain from here on. Based on all your research and reading all of his letters, what would Mark Twain say is his best work?

Ron Chernow: That's a very interesting question, because his answer changed. After he wrote Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, he said that was his best book and that was his favorite. Then later on, and most people don't know that he wrote such a book, he wrote a novel called the Personal Recollections of Joan of Arc. He was obsessed with the figure of Joan of Arc. In later years, he said, "Joan of Arc is my best book. I know it for certain." [chuckles] He was very adamant. He was very dogmatic in his opinions.

Of course, Huck Finn, most people would regard as the most important book that he wrote. Joan of Arc is simply not read anymore. There are a number of books that he wrote that have a kind of charm. Joan of Arc is one. Prince and the Pauper. I remember growing up, we would all read Prince and the Pauper.

Alison Stewart: I read Pudd'nhead Wilson.

Ron Chernow: Pudd'nhead Wilson, A Connecticut Yankee. There are all these books that once upon a time, everyone knew something about them. Whereas I think that now, probably to the extent people know his books, it would be Huck Finn, Tom Sawyer, maybe Life on the Mississippi. He also wrote a hilarious book called Roughing It about his adventures out West.

Again, people think of him just these two or three books. He published two dozen books. This is someone who wrote not only a novel about Joan of Arc, wrote a polemic against Mary Baker Eddy, the head of Christian Science. He wrote a book arguing that Shakespeare didn't write the plays we attribute to Shakespeare, they were really written by Francis Bacon. He even wrote something called 1601, which was a pornographic satire set in the court of Queen Elizabeth [chuckles]. It's sort of a vast amount of Mark Twain that people know nothing about.

Alison Stewart: My guest is Ron Chernow. We're talking about his book, Mark Twain. It's our choice for Full Bio. You describe his style of wit as vinegar, not oil. How was he able to monetize it? How was he able to make a living?

Ron Chernow: Well, he published two dozen books, probably somewhere between 1,000, 2,000 magazine articles, gave thousands of lectures. He was on the lecture circuit, they called it the Lyceum circuit at the time. He probably made more money from lecturing than he did from his book royalties. Then, of course, he married an heiress, even though he completely squandered her inheritance with his crazy speculations.

The tragedy of Mark Twain's life is that, given the fact that he made a lot of money from book royalties and from lecture fees, he marries this extremely wealthy woman. He could have and should have had this easy, placid life, but by his own admission, he said, "I have to speculate, such being my nature." He can't stay away from these speculations. He squanders, in contemporary dollars, literally millions of dollars on these-- forcing them finally, and he also--

Alison Stewart: A printing press. He becomes obsessed with a printing press.

Ron Chernow: Obsessed with a printing press. I know this is a strange story. It was invented by a man named James W. Page. It was a typesetter or compositor. He was convinced that it would revolutionize the newspaper business. He also was convinced that every newspaper in the world would either have to buy or rent the Page compositor. He said it would make him so rich he would be part of the Vanderbilt gang. For 14 years, he's pouring millions of dollars into this machine, including Livy's money, and it goes bust.

At the beginning, he so reveres James W. Page. He says he's the Shakespeare of mechanical invention. Then later on, he's saying, "If I saw James W. Page drowning, I would throw him an anvil." The hero worship went in torrents. He lost so much money on that and then also lost money on a publishing house that he had started, that the family has to close up the house in Hartford and then move to Europe for nine years to economize. Although their idea of economizing [chuckles] was very different from yours or mine. They're in a 30-room villa outside of Florence. They're in a lavish hotel suite in Vienna. It's not exactly clear how they're saving money, but that's what they were saying.

Alison Stewart: Well, part of his reason that he had to go to Europe was also to pay off this huge debt. He had to go and give tours and give lectures that he didn't really necessarily want to do, but he had to do it.

Ron Chernow: That's right. From early on in his career, he was saying that he was going to give up the lecture platform, although he did say at one point that lecturers were like burglars, always promising to give up the trade, but never [chuckles] able to do it. He finds he has to kind of keep going back out on the road in order to pay off all of the debts.

Then finally, he goes bankrupt and actually has to make a round-the-world tour about 12 or 13 months. He speaks in India, Australia, South Africa. It was really rather grueling, but kind of as a matter of honor, Livy was particularly insistent on this paying off every penny that they had lost.

Alison Stewart: While he was on tour, his daughter dies of meningitis. Did he learn anything during that period, not being there with his daughter when she was dying?

Ron Chernow: It's a good question. I sort of wonder what the answer is. What happened is, okay. On that round-the-world tour, he went with Livy, who actually held up surprisingly well, given her health. Then the middle daughter, Clara-- The eldest daughter, Susie, who was in many ways his favorite daughter, Susie didn't go. She was afraid of sea travel. She had a phobia about it, so she stayed behind.

At the very end of the round-the-world trip, Sam and Livy end up in London, and they're expecting the two daughters, Jean and Susie, to come over from the United States to come over to London. Then they get this disturbing telegram that Susie is sick. Livy and Clara immediately have a strong intuition that something is deeply wrong. They get on boat the next day and go back. They were right because she was dying of meningitis.

Mark Twain was not there when she died. He really flagellated himself for years. He said, "If it had not been for my damn speculations, I wouldn't have had to do the round-the-world tour. If it had not been for the round-the-world tour, I could have been with Susie. All of this would never have happened."

You're asking what lessons he learned. A couple of years later, he again gets involved with one of these crazy speculations. He's in Vienna. Of all the letters that I read by him, this one shocked me the most. He discovers that there's a new invention that was designed to print on carpets, and tapestries, and textiles. He spends a day at the American embassy reading about this field. In 24 hours, he feels he's converted himself into one of the world's leading authorities on this.

He had been rescued from bankruptcy by a Standard Oil mogul named Henry H. Rogers. He writes this letter to Henry H. Rogers telling him about this invention and saying that he and Rogers and Standard Oil should buy up the worldwide patent rights to it. He said, "They'll call it a global trust, but that can't be helped." Suddenly, he's gone from knowing nothing-

Alison Stewart: "I know everything."

Ron Chernow: -about this, and that he's going to be running a global monopoly of this. It would have been amazing under any circumstances that he was writing this, but the fact that this was not that long after Susie had died where he's whipping himself for having engaged in speculations which led to the bankruptcy, which led to the round of the world tour, which led to his not being there with Susie.

I really think that if he were alive today, I think the speculative urge was so deep and so uncontrollable, I think he would be in a 12-Step program today. He could not stop. It was a form of gambling. He called it business. but they were all highly speculative. In fact, with the page typesetter, which finally lost the race, turned out there was another compositor from a guy named Mergenthaler that won the race. Twain is absolutely convinced that his machine is going to dominate the industry. It was only Jane Lampton Clemens out in Missouri who asked him, "What if the machine fails?" [laughs] It was the one question Sam never asked himself.

Alison Stewart: My guest is Ron Chernow. We're talking about his new book, Mark Twain. It's our choice for Full Bio, Samuel Clemens, not Mark Twain, but Samuel Clemens was raised by parents who came from families that had enslaved people. It was part of his upbringing. He held beliefs as a teenage boy which you describe as rank bigotry.

Ron Chernow: Yes.

Alison Stewart: Yet he evolved. At one point, he sent a young Black man to Yale Law School. I think the person that I got from the book that really changed his mind, or at least got him to think bigger, was Mary Ann Cord.

Ron Chernow: Yes, this is a fascinating story. Twain used to spend summers in Elmira, New York, where his in-laws had a farm, Quarry Farm. He did a lot of his writing there. He had this very picturesque octagonal study overlooking the river. There was a cook, a Black woman named Mary Ann Cord, who was in her 60s or maybe 70s. She was a very kind of hearty woman. Twain always said she had a smile on her face and laughter in her voice.

One evening, they're all sitting on the porch, and Mark Twain turns to her. He was very, very fond of her, and he says, "How is it," I think they called her Auntie, "How is it that you've never had any trouble in your life?" She looks at him and she says, "Are you in earnest, Mr. C?" [laughs] Then she spills out this story. Again, I don't know if he was really as naive as he was pretending, or whether this was just kind of setting up the story.

Anyway, she then spills out this story. She was born into slavery. She'd married in slavery. She'd had seven children. Then she describes all eight of them being on the auction block. She was, in an instant, her husband and six of the seven children-- Well, actually, all of the children and the husband were torn away. Of the seven, she never saw the husband again. Of the seven children, she only saw one, Henry, who did end up living in Elmira where she was. You can imagine in an instant having your spouse and seven children torn away from you.

At the end, when she finished telling the story, she said, "No, I ain't never had no problem [laughs]. Life is the evidence." What he did, he then wrote an article for the Atlantic Monthly called A True Story, Repeated Word for Word as I Heard It. It was actually the first article under Mark Twain's own name that appeared in the Atlantic Monthly. It was part of this process that you put your finger on, he goes from being having pretty much the racist attitudes that one would expect from someone growing in that town, to becoming a much, much more broad-minded figure.

A lot of it has to do with, well, his relationship with the Langdons- who were abolitionists; they were part of the Underground Railroad- the relationship with Mary Ann Cord. Then there was also a Black farmer, John Lewis, who's working in Quarry Farm in Elmira, whom Twain admires. He saves the family, saves this runaway carriage. Also, he adored-- They had a Black butler named George Griffin who worked with them for many, many years. Had George Griffin been born a century later, he would have been a CEO. He was a very, very smart-

Alison Stewart: Bright man.

Ron Chernow: -bright, smart, engaging. He was their butler. Mark Twain was extremely close. He goes from, again, that sort of crude racist bigotry of his early years to, I think, being as broad-minded and tolerant as probably any other White author of that time.

The most amazing story, which, if I can tell the story, you mentioned it of Warner T. McGuinn, he speaks at Yale Law School and he meets A brilliant young law student, Black, named Warner T. McGuinn. Warner T. McGuin is living with the college's Black carpenter and doing odd jobs. He's in the school, but not fully.

Mark Twain then writes to the law school dean and offers to pay for McGuinn's education because he was so brilliant. McGuinn is the head of the debating society. Mark Twain writes to the law school dean, "We have ground the manhood out of them," meaning the Blacks, "and we should pay for it." His friend, William Dean Howell, said that Mark Twain held himself as a White person personally responsible for what the White race had done to the Black, and that paying for Warner McGuinn's education was part of his reparation- he used the term reparation- for what the White race should do to the blacks.

Now, what happened with Warner T. McGuinn, became a very famous lawyer in Baltimore, won a major desegregation case. Then in his adjoining office, he had a young lawyer named Thurgood Marshall. Thurgood Marshall later said Warner T. McGuinn was one of the most brilliant lawyers he'd ever met. Had he not been Black, he'd definitely have been a judge. It's an interesting line from Mark Twain [laughs] who wanted be going to Brown versus Board of Ed to the Supreme Court. That was money very well spent by Mark Twain.

Alison Stewart: I'm curious if you have thoughts on this. In Huck Finn, they use the N word. I think it's 219 times. Why was that important to Mark Twain?

Ron Chernow: Yes, I think again, probably obvious that he's using the N word not to endorse racism, to expose it. He's trying to show this kind of-- It's almost a pathological repetition of the word. It's unfortunate, the controversy over the N word, which I fully understand it's had a way of kind of associated Mark Twain with racism, even though it's kind of the great anti-slavery book.

It's a hard one, Alison, for me, because [chuckles] I'm Jewish. As I was writing this book, I kept thinking, "Well, what if I was a kid and I had to read a novel where the word [inaudible 00:22:11] was repeated 200 times? How would I feel about that?" Even if I understood the author's intentions, it would still not be a lot of fun turning the pages. Huck Finn is probably banned at all secondary schools. Maybe it is better wait till college, read it with abolitionist literature, slave narratives or something like that. It's really been two areas of controversy with Huck Finn.

The other is the portrayal of James, of Jim. Jim, on the one hand, is [chuckles], I think, far and away the most dignified, insensitive, and noble character in the entire book. Almost all of the Whites in the book are violent and crude and profane and horrible. Jim stands out as almost saintly.

What's the criticism about Jim? Criticism, Jim. This goes back- Black critics, but not exclusively Black critics, going back 50, 75 years, saying that there were certain, they're called minstrel affectations of Jim, particularly. Jim is very superstitious. He's very credulous. They would say this really was not what Blacks were like. This is how Blacks were portrayed in minstrel shows. I think the reason, certainly one of the reasons Percival Everett wrote this wonderful novel--

Alison Stewart: Well, did you read James. Have you read James yet?

Ron Chernow: Oh, yes, yes. I read it. We have the same agent. I had read it even before it came out. No, I think that it's wonderful. I think that what he's trying to do is it's not a debunking book because I think he admires Mark Twain. I think it's kind of more of a corrective that he feels that in Huck Finn boy, he presents a very, very kind of realistic and detailed portrait of this young White guttersnipe, but that he was not equipped to do the kind of fully dimensional character that a Black author could do, so Jim has become James, and it's a great book for people.

Alison Stewart: Do you think Mark Twain would like James?

Ron Chernow: I don't know. The reason that I don't know is this; that I was struck doing the book that Mark Twain was not generous in his comments about other authors.

Alison Stewart: Oh, that's interesting.

Ron Chernow: Hated Jane Austen, hated George Eliot, on and on. He hated Charles Dickens.

Alison Stewart: Oh, that's interesting.

Ron Chernow: Yes. I wouldn't even want to guess how he would react. I've never met Percival Everett, but I've listened to a number of his interviews. In one of the interviews, he was asked, "What would you say to people who want to ban Huck Finn from the schools?" He replied, "I would say they've never read the book." He understands the kind of anti-slavery spirit of it, whatever the limitations. Mark Twain probably went as far as a White person could go, particularly amazing given his own background in a slave-owning state at the time.

One thing that's been very, very nice is when James came out, a million fans sent me an email, "My book club is reading James." Then, often, a month or two later, I'd get a follow-up, "My book club is now reading Huck Finn."

Alison Stewart: Oh, that's really interesting.

Ron Chernow: This has been a very, very fruitful dialogue between the two, and it renewed interest in Huck Finn, renewed interest in Mark Twain.

Alison Stewart: You're listening to Ron Chernow, author of the biography Mark Twain, our choice for Full Bio. After the break. The end of Twain's life. That's next.

This is All Of It from WNYC. I'm Alison Stewart. You're listening to Full Bio, our book series where we spend a few days with the author of a deeply researched biography. Our guest is Ron Chernow, the author of Mark Twain. We've arrived at Twain's later years. Mark Twain believed in women's suffrage and the right to vote. He once said, "There is nothing comparable to the endurance of a woman." Yet as an older man, he engaged in a behavior that would be deemed unsuitable today. Let's get back into our discussion of Mark Twain with Ron Chernow.

After Twain's wife died, he was devastated, and he sought the affections of young women he called his angelfish. He was 70 years old. He said he saw them as granddaughters. People would say, now that is inappropriate behavior [chuckles]. His biographers, they've come on both sides. What did your research tell you?

Ron Chernow: It starts out okay. Livy dies in 1904. By the following year, he's doing a lot of lecturing. Following year, he announces, I'm only going to lecture at women's colleges. He says, I have the college girl habit. It gets worse. Then a year later, he starts collecting. "Collecting" was his verb. He said he started collecting teenage girls between 10 and 16. He called them his angelfish.

They became members of his Aquarium Club. He was the admiral of the Aquarium Club and the sole member. He spent an enormous, enormous amount of time with these, much more time with them than with his own daughters. They would spend entire days and even entire weeks with them. He exchanged hundreds of letters, letters with him.

Now, on the one hand, I tried to both present how this was perceived at the time and how we perceive it now. At the time, he explained his behavior by saying, "I woke up one morning and I realized I had grandfatherly feelings but no grandchildren to expend them on." People regarded this as a charming eccentricity, endearing. Of course, Mark Twain, the bard of American childhood, of course he would want to be surrounded by children.

In fact, there was a well-known actress he knew who showed up at one of his dinner parties dressed as a 12-year-old girl. She said, I want to be a member of the Aquarium Club. It was seen in almost this kind of jocular way. I have to point out, he was never once accused of any kind of sexual misbehavior, or groping, or anything like that. In fact, he was always careful to involve the mothers and the grandmothers who were very proud that their daughters were spending all this time with Mark Twain.

Having made all those qualifications, we perceive this as really peculiar and disturbing. There's something going on. He said he had grandfatherly feelings. Well, why no boys? Why only girls? You could see we have very kind of detailed accounts of him from his then secretary, Isabel Lyon, who was in her 40s, who was often the chaperone.

Alison Stewart: Oh, she's a piece of work [chuckles].

Ron Chernow: She's a piece of work. She's often chaperoning the girls. You could tell from reading her daily diaries, there was like an obsessive quality to this. Not only in the amount of time that he spent, but when the girls were about to arrive, she would portray him nervously pacing in front of the door and looking at his watch, and, "When is she going to arrive?" It was too important. He was too preoccupied with these girls. He'd been so embittered and disillusioned by life, and he said they're naive and they're innocent. He had all of these explanations, but I have no doubt how modern readers are going to react to this.

When I was doing the research, I read a biography of Lewis Carroll because there's a certain parallel. In the case of Lewis Carroll, he was collecting nude photos of girls. He was collecting nude drawings of girls. There's nothing like that with Mark Twain. What was sort of going on under the surface psychologically with him, oh boy, if we had him on the analytic couch today, we would have some questions about that for sure.

Alison Stewart: I did want to ask about Isabel Lyons, as we're wrapping up. She was sort of his right-hand woman. She had control of the house. She kind of became sort of we called a work wife, for his life, but she did work for him. She managed to get power of attorney, and it went dark. The relationship went very, very dark. People read it, but he did terminate her. What did Isabel reveal about Mark Twain in his old age?

Ron Chernow: Well, I think what happened-- Okay, so Livy dies. As I was saying earlier, his wife had really organized his life. He didn't know how to do that himself. After she died, he said, I don't know how to plan. She did all the planning. See, he's not only bereft emotionally, he's lost in terms of just how to live his life. He had hired Isabel Lyon because his wife had, over an extended period, died of congestive heart failure.

He'd hired Isabel Lyon essentially to be his secretary. After Livy dies, Isabel Lyon not only is a secretary, but she's assuming all these responsibilities, all these things that Livy had done. She becomes the hostess, she's organizing the household, she decorates his new house, goes kind of on and on, and she really kind of takes over his life. Now, what Mark Twain never admitted was he'd kind of let this happen. Isabel was a single woman in her early 40s in an era where if a woman was 25, they'd start calling her an old hen.

Here's this woman who understandably would be concerned about her future and her security. She falls in love with Twain. In fact, her nickname for him, which she used constantly, was the King, and she's kind of shivering with delight. There's also a designing quality about this as she's kind of taking over the household, taking over his life. It's a sad story.

Actually, there have been two detailed books written about her; one very sympathetic that she had adored Mark Twain, had served him tirelessly for all these years, and then he boots her out of the house, and then another book taking the opposite side that she got what she deserved. I'll kind of let people read it.

Mark Twain announced during the last few years of his life, he said, "I've worked hard my whole life. I just want to play." He doesn't want to take responsibility for anything. It creates a kind of vacuum in which all sorts of terrible things happen. In particular, his youngest daughter, Jean, was epileptic. He really did not have the luxury of opting out of this because he wanted to have a second childhood. Jean was, in many ways, the worst casualty because Isabel did not like Jean and wanted to keep Jean out of the house.

Alison Stewart: Keep her in a sanitarium.

Ron Chernow: Yes.

Alison Stewart: He died in April 1910. What changed for you as a writer about how you thought about Mark Twain when you finished the manuscript for this book?

Ron Chernow: Let me go back to when I first developed this Mark Twain obsession. I was 24 years old, I was living in Philadelphia, and I saw one night that Hal Holbrooke was giving his one-man show. He stood up there for 90 minutes in the white suit with the cigar and the unruly mustache, and he told one political witticism after another. For many years, that was my image of Mark Twain. There's truth to it he was charming, irreverent. He was hilariously funny. He was perceptive on every topic under the sun.

I think in terms of doing the book, he turned out to be so much more complicated a man, and moody, and temperamental, and difficult under the surface. There are so many different sides to him. You never feel that you really quite get to the bottom of the man. It's a little bit humbling for the biographer to say that.

Someone asked me the other day did I end up admiring him. I guess what I would say, I was simply amazed by him, amazed what he had created. He was completely, completely self-invented, no less than Alexander Hamilton, actually. Somewhat similar kind of story as teenagers, sort of pretty much almost orphaned. He goes out there in the world and creates this personality and sets the world on fire. He becomes he's very erudite. He was an autodidact. He educates himself in all sorts of subjects. He was an utterly remarkable man, but he could be vengeful. There were these dark sides to him.

Part of the fun, if that's the right word, of doing the book, is that I was wrestling with him every day. Who is this man? What is his ultimate nature? His relationship with Livy is you can't ask for a husband who was more tender or devoted. Then he goes- there's this crazy business with the angelfish. This is the same man.

Alison Stewart: What's your favorite Mark Twainism?

Ron Chernow: Well, there are two that I particularly like; one funny and one wise. The funny one is "Good friends, good books, and a sleepy conscience: that is the ideal life." The one that I find very, very wise is, he said, "The two most important days in anyone's life. The day we are born and the day we find out why."

Alison Stewart: Ron Chernow has written the book. Mark Twain. Thank you for your time today.

Ron Chernow: This was great, Alison. Thank you.

Alison Stewart: Thanks again to Ron Chernow. Full Bio is produced by Jordan Lauf, engineered by Juliana Fonda, and written by me.