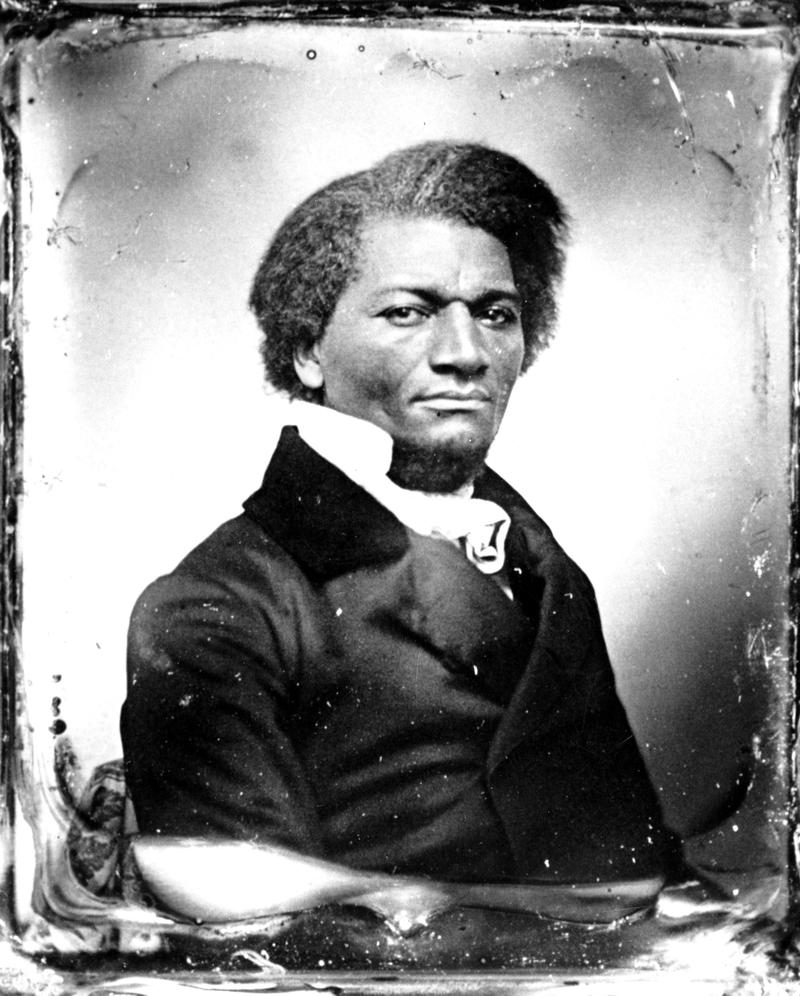

Frederick Douglass and His Relationship with Lincoln (Full Bio)

( ASSOCIATED PRESS )

[music]

Alison Stewart: This is all of it on WNYC. I'm Alison Stewart. All day on the show today we're discussing the massive biography Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom by David Blight, professor of history at Yale. For this segment, we'll look at Frederick Douglass the politician. He was embraced by the Republican Party, different than the one we know today, and campaigned for every Republican candidate for president after the Civil War, but that doesn't mean he and the party always saw eye to eye. For example, Douglass was a critic of Abraham Lincoln early on. He was concerned that the president didn't initially support Black men fighting in the Civil War. Once they were allowed to fight, including two of Douglass's own sons, they were paid half of what white soldiers were being paid to fight. To be clear, Lincoln wasn't an abolitionist but rather was concerned with what would keep the Union together. Later in his life, Douglass became a bit of a regular figure in DC.

By this time, he was an elder and found himself publicly at odds with emerging Black leaders like John Mercer Langston, one of the first African Americans to hold elected office in the United States, and Richard T. Greener, dean of Howard Law School and the first Black graduate of Harvard. I asked David Blight about whether he considered Douglass a political figure leading up to and during the war.

David Blight: Oh, yes, he's an enormously political figure. Politics though, like for all of us, for Douglass, was a learned instinct. As we said earlier, he came of age as a Garrisonian abolitionist. He was supposed to denounce politics and denounce voting. He's not doing that any longer by the early 1850s. Douglass in the course of the 1850s in particular learned to a degree the craft of politics, but this is politics from outside of political circles, outside of political parties by and large, and certainly outside of the government. Douglass became in the 1850s in his newspaper an extraordinarily astute analyst of American politics, and especially of the question of slavery in American politics.

He desperately wanted to wield influence if he could. The trouble is he couldn't by and large. He was running a newspaper up in Rochester, New York. He was on the circuit giving lectures and speeches, but he was never inside any particular political body. However, with the Civil War and its revolutionary transformations, he begins to get inside the politics of the Republican Party. He's not at first, but eventually, he is, especially after emancipation, especially after his three meetings with Abraham Lincoln. It was almost a fourth. Douglass becomes, by the end of the Civil War and certainly in the early years of Reconstruction, that fascinating example, at least I made this a major theme of my book.

He is the old radical outsider who becomes a political insider. That's a journey that we've seen other times in American history. Look at all the leaders of the modern civil rights movement who then got elected to office as mayors and as congressmen. Then there was this young guy named Obama who actually got elected president, for God's sake. What happens when you're inside of power? What deals do you have to make? What compromises do you have to make about principle? Douglass lives that story as the prototype of that for the rest of American history, but he had tremendous political instincts.

It took time to develop it, but he had an astute understanding of politics as power and finding ways to wield it and to bend it. His frustration was always, of course, that abolitionists had so little power. They were always on the outside knocking on the doors to get inside. Even when he got inside to some degree with Republicans during Reconstruction and in the wake of Reconstruction, and then when he even got three federal appointments, one as marshal of the District of Columbia, another as recorder of deeds for the District of Columbia, and third as us minister to Haiti in 1889, he had relationships with every Republican president.

Alison Stewart: I want to talk about those presidents. Let's dive into that. Let's start with Lincoln. In a chapter titled The Kindling Spirit of His Battle Cry, we learn about Douglass and Lincoln, a relationship you describe as difficult but eventually historic. How did they view one another initially?

David Blight: At arm's length, at least. In fact, Douglass was a ferocious critic of Lincoln in the first year, even year and a half of the Civil War, until Lincoln finally came out publicly for emancipation with the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation in September of 1862. Douglass's struggle the first year of the Civil War was whether to trust the Republicans, whether they really were as anti-slavery as they seemed to portray themselves. That relationship, though, took hold particularly in 1863 with their first meeting. August of '63, they meet in Washington, but that was at Douglass's demand. He didn't have any invitation. He went, in effect, to protest discriminations against Black soldiers in the army.

As they say in diplomatic circles, they had a useful exchange of ideas. They didn't entirely agree, but Douglass did tell us after that first meeting with Lincoln at the White House in '63 that he was impressed with Lincoln as a person. In fact, I think he was awed by Lincoln because Lincoln at least took him seriously, sat and talked with him. In fact, Douglass walked away from there and wrote that he'd never been treated so straightforwardly and honestly by a white man with power as he had been by Lincoln.

Their second meeting, though, is the great one. It's a full year later. It's August of '64. The war is in a horrible stalemate. Lincoln believes he may not be re-elected in the election of 1864, and with good reason. The Democrats are just pummeling the Republicans as the party of emancipation and doing pretty well at it. Lincoln invites Douglass as the principal spokesman of Black America to the White House.

They have probably a full-hour meeting at which Lincoln asked Douglass, looked him in the eye and wanted him to be the chief agent of a scheme that would funnel as many slaves as possible out of the Upper South into Union lines and into the northern states and into some version of legal freedom before election day in case Lincoln wasn't reelected. Douglass, I'm convinced, sat there and probably looked back at Lincoln and just was speechless. Probably didn't know what to say. He was being asked to organize some kind of John Brown-style system to funnel slaves out of the South.

Douglass didn't have a clue how he was supposed to do that. All he was told was the War Department and the army will help you. He goes back to Rochester. For almost two weeks, he starts sending letters and telegrams to his friends and abolitionists and people who'd been recruiters of Black troops, "Here's what we're going to do. I don't know how, but here's what we're going to do."

He was saved. None of this ever happened because of what happened on the ground in the war. Atlanta fell to Sherman first week of September. Even before that, Mobile Bay fell to Admiral Farragut August 25. Phil Sheridan's army began to move down the Shenandoah Valley right in the beginning of September and the war changed and northern morale changed for the better. Lincoln's re-election by September and into October looked much, much more likely.

The last time they will meet is, of course, right after the second inaugural address. Douglass was in the crowd. Douglass went to Washington. He was going to be there. He was off to Lincoln's left down in the crowd. And after the speech, which Douglass thought was fantastic, he went on to Pennsylvania Avenue and he just walked all the way to the White House following the presidential carriage. He didn't have an invitation, but he just got in line. He put through his card, he said, "I'd like to come into the reception." They said, "No, sir, you can't." Douglass tells us that he said, "Tell President Lincoln that Frederick Douglass is out here." Two minutes later, the police came back out and said, "Yes, come on in."

In the East Room in a big reception, they spy each other. Lincoln comes over to Douglass, and according to Douglass recollection, Lincoln asked Douglass what he thought of the speech. This is the great second inaugural. "Every drop of blood shed by the lash shall be paid with blood shed by the sword," and so on. Douglass tells us that he told the president, "No, sir, it doesn't matter what I think. Attend to all of your guests."

Lincoln said to Douglass, "No, no, no, I want to know what you think." Douglass tells us he said, "Mr. President, that was a sacred effort." Now, that's a very good description of that speech. It's a very biblical speech. It's very old Testament speech. Then, of course, Lincoln was assassinated one month later or five weeks later. The irony there is-- There are many, but Lincoln had invited Douglass to come have tea in late March at the Soldiers' Home, which was this retreat where Lincoln and other presidents would go.

Who knows? That might have been a much longer meeting, but Douglass had to turn down because he had a speaking engagement and he couldn't go. Then Lincoln was killed, of course, April 14 and he was gone. From that point on, Douglass will campaign for every Republican candidate for president the rest of his life. Grant, twice, Hayes, Garfield, and Harrison and so on and so on. He became a stalwart of the Republican Party in the sense that he supported the Republican candidacies no matter who it was.

Alison Stewart: Can we talk about Andrew Johnson for just a moment? [chuckles]

David Blight: Sure.

Alison Stewart: Douglass said of Johnson, "Whatever Andrew Johnson may be, he's no friend of our race." It's incredibly vivid in your book, a very public argument. I don't know, what should we call that? A very public back-and-forth between the two men. What came of this fight?

David Blight: It was a terrible exchange, wasn't it? It's in February 1866. It's in the midst of the struggle in Congress to try to come up with a reconstruction plan. Douglass gets up a delegation of 12 Black men, including his oldest son Lewis. They got an appointment at the White House to meet with the president, Andrew Johnson. They went with various pleas and ideas they wanted to discuss, especially the right to vote, but they never even got to speak, really. Johnson held forth and preached at them, in effect, for about 45 minutes. He told them, "If it weren't for your people, this war wouldn't even exist. This can never be a country that's truly biracial."

He even said things like, "I once owned some slaves, but you know I freed them. Even when I owned slaves, I was more their slave than they were of mine." It got worse from there. As the leader of the delegation, this is at the White House, Douglass kept raising his hand and he would say, "Mr. President, may we-- Mr. President." At one point, Johnson said, "Be quiet, I'm not finished," and it just deteriorated from there.

Here was a president of the United States spewing this racism at a delegation of 12 Black men who've come to talk to him about their futures. As they were leaving the room, Douglass got the delegation to stand up. They just realized this isn't going anywhere, it's over. They're about to leave the room. By the way, the press was there recording this. Johnson was overheard to say, "That Douglass, he's just like every other N word. He'd sooner cut your throat than not."

Now. I have always had this imagination, I don't know exactly what Douglass was thinking, but Douglass must have turned around and not have given anything to see his eyes meet Johnson's at that point. What we do know is they went back to a hotel, they wrote up a manifesto that was published the next day in a Washington, DC newspaper, and then Douglass went to his desk and he did what he always did.

He wrote a new speech. He took it on the road for the next six months. The title of that speech was The Perils of Our Republic. He developed not just a critique of Andrew Johnson, he skewered Andrew Johnson as the great danger to the future of American democracy. In that speech, he laid out a whole scheme of measures that he believed should be done to thwart and stop Andrew Johnson. That was their only significant encounter. There's no question, Andrew Johnson was the worst possible thing that ever happened to the potential of the future of Black rights. He was, above all, a virulent white supremacist.

Alison Stewart: That was part of my conversation with historian David Blight about his biography Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom for our July 4th show today.

Copyright © 2024 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.