Flavors And Recipes As A Gateway To The Past

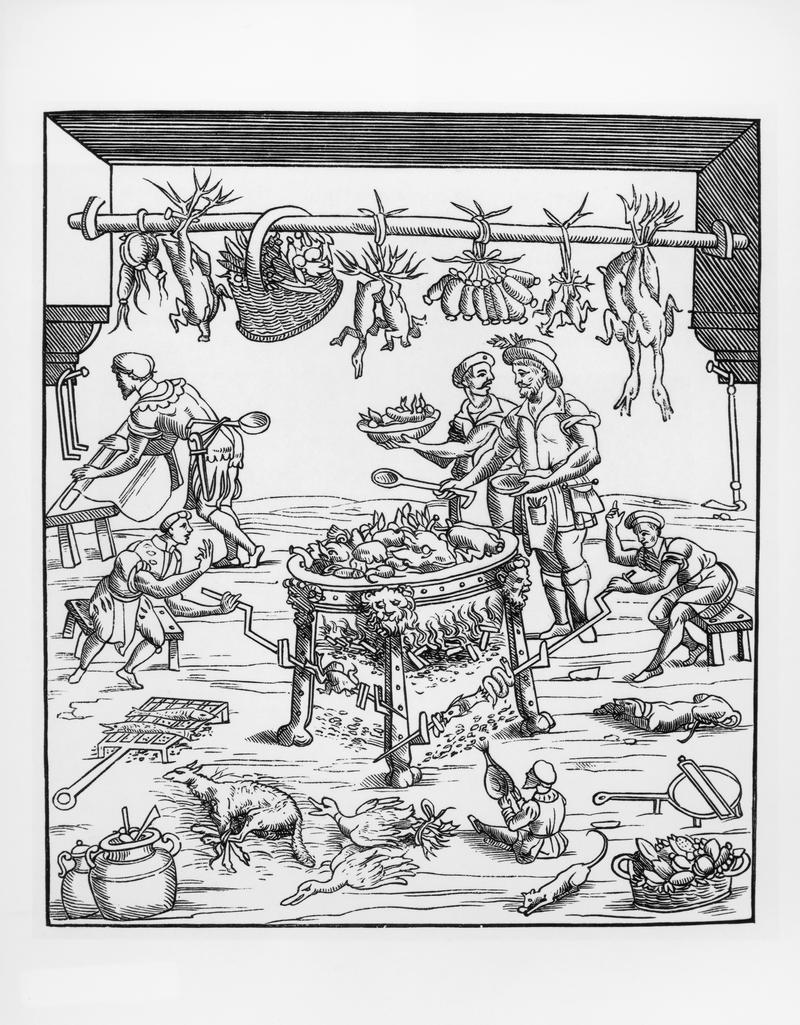

( Photo by © Historical Picture Archive/CORBIS/Corbis via Getty Images )

Alison Stewart: This is All Of It on WNYC. I'm Alison Stewart. Coming up on tomorrow's show, we are going to talk about one of our favorite things around here, Broadway. The latest issue of New York Magazine is an homage to the theater legends and its history.

We'll be joined by David Haskell, who edited the issue, and Mark Seliger, who took the beautiful photographs of some of Broadway's most recognizable legends, Bar Streisand, Mandy Patinkin, Audra McDonald, Andre DeShields.

We want you to call in and share your favorite Broadway legends or moments. That's happening tomorrow at noon. On Sunday at 8:00 PM, WNYC is rebroadcasting our listening party live with the cast and creative team behind the musical Hell's Kitchen. It's Broadway on the radio, coming up tomorrow and this weekend. Now let's get this hour started with Tasting History.

[music]

We love history on All Of It. We encourage you to read books about it. We tell you about visiting a museum or watching a documentary. Now, a YouTube channel brings history to you and your stomach. It's called Tasting History with Max Miller, who looks for recipes and other primary resources related to food cultures, from an ancient Rome recipe for stuffed flamingo, to the origins of the Girl Scout cookies and everything in between.

It aims to get folks to understand a small piece of what it was like to live in the past using the universal language of food. Humans haven't always had grocery stores, refrigerators or food processors, but we've always had to eat. To join us now about Tasting History with Max Miller is Max Miller. Hi, Max.

Max Miller: Hi. Thanks so much for having me.

Alison Stewart: You describe this channel as being about history first, food second. Why did you first want to look at history through the lens of food?

Max Miller: I've always been obsessed with history since I was a little kid. It was actually history that got me into cooking and to baking, specifically, The Great British Bake Off. When I first started watching that in the early seasons, they would often talk about the history of what they were baking.

Unfortunately, they've gotten rid of those segments, but that's what got me interested. That was the hook for me. I have turned it around and found that to get people into history, food is a good hook because everyone likes food. I like teaching history, so this is my sneaky way of teaching people lessons.

Alison Stewart: You have different ways into the story. Sometimes it's something very specific, like what they served in first class on the Titanic, or perhaps it might be the oldest recipe on record. How do you go about choosing historical subjects to explore?

Max Miller: It's hard. It almost always comes with the story first. Like I said, the history is what got me. I like to find an interesting story. If it has anything at all to do with food, I can find a recipe to go along with it. Sometimes it's very clear, and I end up really just talking about the history of the food itself.

Then sometimes it's very tangential, and it's like, "Yes, they served this on the Titanic," but really what I'm going to talk about is the sinking that night and how first or third class passengers experienced that night differently.

Alison Stewart: What do you think we get about history by engaging our other senses, like their sense of smell, our sense of taste.

Max Miller: Immediacy. It is one of the only ways that we can really connect with people from the past. We can use our imaginations, of course, and imagine what it was like to be a soldier at the Battle of Waterloo, but it's really just going to stay in your imagination and you don't know if you're right or wrong or anything.

If you taste something using a recipe that they used back then, even though our ingredients have changed and everything, at least you can get this immediate connection with someone who lived hundreds of years ago in many cases.

It makes people more interested in it. By the time I get to the history section of a video, I think people are more willing to listen to me babble on for 10 minutes about whatever topic I've decided to talk about that day.

Alison Stewart: We're talking with YouTuber and Food History enthusiast Max Miller. His channel is called Tasting History. He's got a cookbook out of the same name. Let's get you in on this conversation. Maybe you have a question for Max Miller. Our number is 212-433-9692, 212-433-WNYC.

Maybe you have an old family recipe that he can add some historical context to, or maybe you have a question about a particular ingredient or a time period like why'd the potato get so popular? Give us a call, 212-433-9692, 212-433-WNYC. You can also hit us up on social media at All Of It WNYC.

You use primary resources in all of your research, but sometimes a recipe will have something that doesn't exist, the ingredient no longer exists. What are some of the challenges of these eccentricities in recipes that make it hard for you to decipher, "How am I going to do this?"

Max Miller: Usually, my number one mantra to myself so I don't go crazy, is it's just food. This is not surgery or anything. I just need to get as close as I can without often breaking the law. There is a dish for a bear stew that I want to make, it's a Mongolian bear stew. You can't get bear meat legally here in the US, at least not commercially. I'm going to have to use something else.

I still want to tell this story of Kubla Khan eating in in his palace after they had taken China. Then sometimes it's not that I can't get a hold of ingredient because it's not available, but because it literally does not exist anymore. Most famous is silphium, which was one of the most popular ingredients, at least among the wealthy, in ancient Rome. It was so popular that they ate it into extinction rather early on. It was during the reign of Nero.

For the majority of the Roman Empire, this ingredient didn't exist. What's nice is that because they loved it so much, they went and found a substitute. It was a poor substitute, but it was a substitute. That's called asafetida. That is still available today sometimes under the name Hing. You can get it in Indian grocery stores. They use it a lot in their cooking.

Then there is those times where we simply don't know what the ingredient was. This often has to do with language barriers. If you go back to Babylonian cooking, we have the Yale Babylonian tablets. It's all cuneiform. They are the oldest written recipes, but there are a lot of words that have no translation. Some have theories of the translations, but even scholars can't quite agree. It's just unclear.

Even when you come much later in history, words that we use now to refer to foods have just changed.

Alison Stewart: Like what?

Max Miller: If you were going to cook something with pickled mango today, you would assume that it is mango that has been pickled, but if you were in England in the 1860s, that could be a peach or an apple or a plum, or a whole host of other things. It was simply because they were trying to emulate what they were getting from India, but they didn't grow mangoes in England, so they had to just use other things.

Alison Stewart: This is a great text for you. "My family discovered Max on YouTube during COVID. He provided Us with many hours of entertainment and education during a bleak time. Many thanks to him." Wanted to pass that along.

Max Miller: Oh, that's so nice. It was definitely a wonderful way for me to get through it as well.

Alison Stewart: No doubt. Let's talk Easter. We're approaching Easter, in an episode about an Easter cake which is called. How do you say it? Simnel?

Max Miller: Simnel cake.

Alison Stewart: A Simnel cake. You say that most of what people think they know about this cake comes from folklore, but because in your words, the Victorians just love making things up.

Max Miller: They did.

Alison Stewart: What kind of skepticism do you have to have when you are going through a recipe?

Max Miller: It's usually not the recipe itself, it's the history behind it. If there is a wonderfully crafted origin story where there's a lot of specific information about people's names and dates, and it's just tied up with a bow, it's probably not true because typically people, when they create a dish, they don't write down.

Today I created this first cake that now I am going to call Simnel cake. Today we do do that here in the last 100 years. We know Peach Melba was created and named after Nellie Melba, the opera singer, but historically, that's not how food happened. Sometimes the stories are pieced together, and then sometimes, especially with the Victorians, the stories are just made up.

They loved giving origin stories for things. I don't know exactly why that was, but it was popular. Now it's sorting through the fact and fiction and finding, are there even older records that corroborate this story, or do we think it's totally made up? Again, it's always like, this is just food history, so it's not super, super important. I do like to get to the bottom of things as much as I possibly can.

Alison Stewart: To the best of your knowledge, what are the origin stories behind this Simnel cake, and what made it a good centerpiece for Easter celebrations?

Max Miller: There are a few. There's the boring one, of course, that's probably true. That just has it coming from an older word for flower. They would make these little cakes, but they were just bread, and they were called Simnels or Simna. Later on, there is an English king who his power was-- There was a young boy named Simnel who had claimed to be the descendant and the rightful heir to the throne of England.

This does have some basis in truth that this actually happened. The fact that he worked in a kitchen and there made the first Simnel cake and so it's named after him, doesn't really have any basis in truth. Again, that's like, let's take some truth, let's take some fiction, and we'll make a fun story again. That's something that came up in the Victorian age.

Another even less true story is about a husband and wife team that were bakers. One was named Simon, who they called Sim, and another name Nelly, who they called Nell. One day they had a disagreement over making a cake during the last days of Lent, just before Easter. One wanted to boil it, one wanted to bake it. They decided to do both, and so they put their name on it, and that became Simnel.

That's a type of Simnel that is not what I've made, but that is a type of Simnel that's out there, boiled and baked. The reason that it ended up becoming associated with Easter is a little murky. Exactly why this time of year, it's not that there are ingredients involved that are only available now or anything like that, but typically Easter is a time historically where sweets are re-added to our diet.

During the weeks of Lent, you couldn't eat so many of the things that you really wanted to eat. There was no butter, there was no milk. You couldn't have anything that came from an ant animal unless it was seafood for the longest time. You see a lot of cakes being made at this time of year.

It was always traditional to have it be made on Mothering Sunday, which is the fourth Sunday of Lent, and then it would be served a week later on Easter. I don't know why they ate it a week later, but it does let the flavors inside, I guess, marinate a little bit.

Alison Stewart: We're talking to YouTuber and Food History enthusiast Max Miller about his channel called Tasting History. There's a cookbook out of the same. You have a dessert you call History's oldest dessert Mersu. Am I pronouncing it correctly?

Max Miller: Mersu, yes. We think that's how it should be pronounced.

Alison Stewart: What is this recipe for Mersu, perhaps the oldest dessert? What does it tell us about food culture in this extremely early civilization?

Max Miller: It isn't even really a recipe. It's more of a list of ingredients. The ancient Mesopotamians kept very good records, especially in the palaces and in the palace of Mari, which is a ways north of Babylon. They found a receipt detailing some of the ingredients to make Mersu for the king. Exactly what Mersu is, it does not explain. Other sources give context.

It was probably some baked good that had sweet fillings. This one is with dates and pistachios, but there were many others. They also had savory fillings, but we really don't know what it was. Any modern recipe for it is really just a guess. It's an approximation, but we can at least get an idea. What's interesting is that to this day there are desserts in that region that are very similar, at least in the ingredients.

We can wonder maybe this hasn't changed all that much over the centuries. There are other dishes from that time that have remained almost static to this day, which is really, really neat. It just show how varied food was at that time, even that far back, because we have records of numerous people making this Mersu in the city of Mari, and that's the only thing that they made.

It was pastry chefs who specialized in just making these fill in the blank cakes, breads, pastry, we don't really know. Food was obviously very, very important just as much to them as it is to us. Again, it gives us that immediacy that even though they were living nearly 4,000 years ago, they had the same desires, wants, hang ups. Nothing has changed.

Alison Stewart: You're listening to Max Miller, YouTuber and amateur food historian. The name of his channel is Tasting History. We'll have more with Max, including the history of the first Girl Scout cookie after the break.

[music]

You are listening to All Of It on WNYC. I'm Alison Stewart. We're talking with YouTuber and food enthusiast, Max Miller. His channel is called Tasting History. He's got a cookbook of the same name. We're talking about history through food. Here's a question for you.

This says, "We love Max Miller in our household. We have a tattered family copy of the White House Cookbook with some odd measurements. I know that you have methods for converting measurements across time. What kinds of tools or references do you use to approach the conversions? I think it would be so lovely to connect with family history through previous generations cookbooks." How do you make the conversions?

Max Miller: The White House cookbook is really interesting because it was huge. It was so popular, everyone in this country had a copy of the White House cookbook in their kitchens for decades. It is written in a late 19th century style. That's when it was first produced. You do have ingredient measurements that are like two teacups of flour. Whoa. How much is a teacup? A lot of things like that. Often wine glasses.

Wine glasses were vast different than we have today. A wine glass is really just about an ounce, whereas today a wine glass would be I don't know, 12, 16, 18 ounces more. Making those conversions, it does take a lot of work. Late 19th century conversions are easier because we do have-- That was the time when things started to be standardized.

We do have books from that period and from the early 20th century saying, "Two wine glasses equals this many ounces or milliliters. This many teacups is this many tablespoons." A lot of old cookbooks from this period actually have those charts. You can find them online either in cookbooks or sometimes if you just look up, like 19th century measurement conversions, there will be websites that lay these out.

The thing is, they're still not consistent because everyone was deciding different things. What makes it even harder is that even today, it's different. National weights and measurements are not the same across the world. A cup of something or even a pound of something 18th century Russia is different than a pound of something in 18th century England, is different than in France.

In France, if you go back to the 17th and 18th century, measurements will be different city to city. You have to find out, "Was this written in Paris or was this from Rouen?" Because they're going to be slightly different amounts. The standardization of measurements is something we take for granted now, but it is relatively new. It does make things difficult. For a lot of cooking it doesn't really matter too much. You can approximate it. When it comes to baking, it's a little bit more difficult--

Alison Stewart: Because baking is partially chemistry.

Max Miller: The differences can be substantial. It can be 10%, 20%, 30% different. If you use 30% more baking powder, that cake ain't going to taste good.

Alison Stewart: You had an episode that talked about the history of the Girl Scout cookie. It talked about the basic sugar cookie. How is it different from what we expect from Girl Scout cookies today?

Max Miller: I think the main difference was not the cookie, it was who was making the cookie. It was the Girl Scouts. They had to bake the cookies at home. Or actually it was more often they would rent the space of a store that sold ovens, and then they would use those Ovens to bake the cookies and then sell the cookies after that. There are no Girl Scouts today, I don't think, that are actually baking any of the Samoas and Thin Mints out there. Now it's all commercial kitchens.

It's only a couple, actually in the country that do it all. That's the main difference, because the cookie itself is essentially just a delicious sugar cookie. The recipe is from 1922. That was the first year that it came out. The cookie tastes the same as it would today, any sugar cookie.

They don't make those anymore now. That ended up becoming the trefoil, which is a shortbread, which is quite different. That's the biggest difference, was who was making the cookie and the cost, of course.

Alison Stewart: At the end of your series, you eat what you've made. Do you ever get any surprises? Perhaps you don't like it that much.

Max Miller: Yes, all the time. That is because I never go into an episode trying to make something delicious. If it is, that's great. My goal is to make something as close as I can to the way that it was made and hopefully have an interesting story behind it. If it's delicious, great. If it's not, it's not my recipe, I don't care. There are dishes from history that just don't sit well with me.

There is a jellyfish, it's called a patina, which is basically a frittata from ancient Rome. Turns out I'm not a huge jellyfish fan. The texture is not great. I also really don't like frittatas all that much, it turns out. That was rough. I once did an episode on the history of eating leather. There are times in the past where people had to eat leather to survive because it was literally the only thing that they had.

They had their leather bootstraps or whatever, and they were starving. They would boil the leather until it became edible. There isn't a lot of nutrient left, but it was something to fill their stomach that wouldn't poison them. I found some raw leather, which was not easy to find, and actually boiled it and tried it for myself. That was a little rough because it's leather. It wasn't great. Again, the story was fascinating around it.

Alison Stewart: Took one for the team. We appreciate that. The name of the channel is Tasting History. We've been talking with Max Miller. Max, thanks for making the time today.

Max Miller: It was my pleasure. Thank you so much for having me.