'Dear Ms.: A Revolution in Print' Celebrates Ms. Magazine

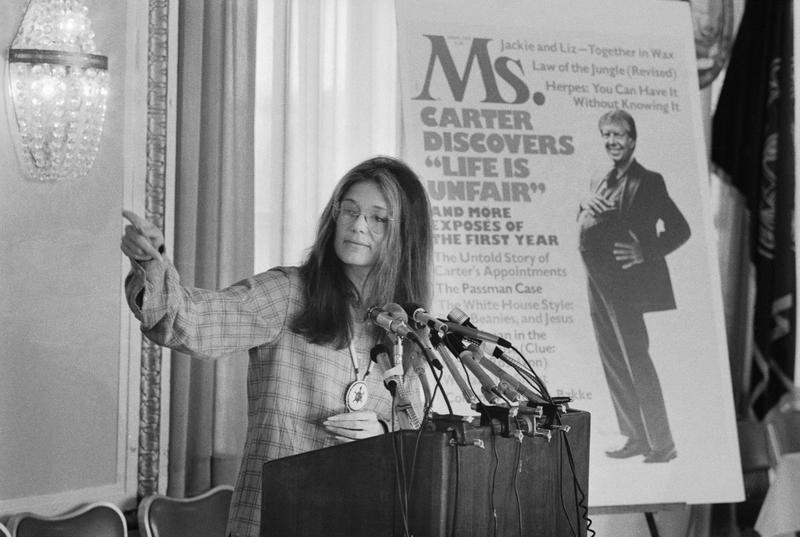

( Photo courtesy of Bettmann via Getty Images )

Alison Stewart: This is All Of It on WNYC. I'm Alison Stewart. Ms. Magazine launched as an insert in New York magazine in December of 1971, founded by Gloria Steinem and a team of female editors, including Patricia Carbine and-- Did I say that right? Carbine. Thank you, Patricia Carbine and Letty Cottin Pogrebin. Gone were the stories of gardening and sewing. Instead, the magazine was the first to focus on issues like domestic violence and workplace harassment. It became an influential voice on topics like civil rights and pornography, even if it wasn't perfect and sometimes let certain voices out.

In the new documentary, Dear Ms.: A Revolution in Print, three filmmakers each take on a chapter in the magazine's history. The directors are Salima Koroma, Cecilia Aldarondo, and Alice Gu. All three join me now. I hope I got your names right. Welcome to the studio either way.

Alice Gu: Yes, you did.

[crosstalk]

Salima Koroma: Thank you for having us.

Alison Stewart: Dear Ms. screening at the Tribeca Film Festival this week, and it will come out on HBO later this summer. This is for you, listeners. Get in on this conversation. Were you or are you a Ms. Magazine reader? What did you think when Ms. First came on your radar? How has the magazine influenced you? What did it cover well? What did it cover not so well? You could give us a call. 212-433-9692, 212-433-WNYC. As we wait for our calls to come in. Salima, we'll start with you. It's a three-part documentary presented as a single film rather than a series. First of all, where did the project begin, and how did you work with your fellow directors?

Salima Koroma: I've never worked with other directors before on one film. It was when you think about what Ms. Magazine was, it's the startup. It feels like this idea that was like a utopia where women get to put in all of their ideas, things they cared about. This project, it mirrors that for me. Getting to work with other women and getting to hash out different ideas the way we think about it. That's the spirit of this story for me. Then when you watch it, it's so interesting how I interpret something and how Alice interprets it, and then how Cecilia interprets it. I would have never thought to do it that way. It's so beautiful. I think it came about in that spirit, the same spirit that Ms. Magazine came about.

Alison Stewart: Alice, how did you get involved?

Alice Gu: I got a really wonderful phone call one day from a woman named Dylan McGee asking if I'd be interested in working on Ms. with a couple of other directors. I emphatically said yes. This was something that was so exciting for me. Like Salima, I had never-- I don't even know if it's called co-director. We each direct our part. I've never worked with other directors before. I wanted to piggyback on Salima's point that it is so interesting to see different points of view, and that's why it is so important. We're three very different women. I feel like-- similar in many ways and very different in other ways. That's reflected in life and how we view the world, and how our art comes out.

For that reason, I'm so, so, so excited to share this with the world. I love the format. I think HBO took a big swing with this, with three different directors telling one cohesive film. I'm so very proud of it and so proud to sit alongside these two women.

Alison Stewart: Cecilia, why did three directors work on this film?

Cecilia Aldarondo: Just to follow what they're saying, I think of it like a prism. You know how a prism, the different facets refract upon each other. To me, ultimately, Ms. was such a phenomenon because the women's movement was a phenomenon. Every social movement, in order to be successful, needs to be diverse, needs to represent a whole range of experiences, and with all the complexity that that entails, and sometimes the infighting that that entails.

Again, I think that this approach enables us to take a step back and think about Ms. as something that was always a collective endeavor. It was always about trying to cast a wide net and represent the diversity of women's experiences, and sometimes that was really hard to do, so I think-- I just want to also reiterate how much faith HBO put in us. They really trust their filmmakers. We were given a brief. At the same time, we were given a lot of freedom to be ourselves.

Alison Stewart: Salima, there were women's magazines before Ms. They concentrated on sewing and gardening. How did Ms. lay out its mission when it first started?

Salima Koroma: The idea was that part one is a magazine for all women. The idea was seeing all these different perspectives. One thing that we all have in each of our parts is this idea, "Dear Ms." or these letters. These letters of women from all over the world saying, "Hey, I have that same experience. I didn't know what to call that. Sexual harassment-

Alison Stewart: That was interesting. Yes.

Salima Koroma: -in the workplace. I didn't even know there was a name for that." I think it was this magazine that got to put a name to a lot of things that were happening to women that they had never been able to speak about.

Alison Stewart: Cecilia, in your part of the documentary, it touches on the no comment section. Will you explain how the no comment page worked?

Cecilia Aldarondo: Yes, one of my favorite things about Ms. If you can get a back issue of Ms., or if you have any at home and you can dig them out. It's such a fascinating magazine because it had a lot of different aspects to it. One of the staples became this thing called no comment, where often readers would submit, but also editors would find things where they would simply reprint advertisements, bits of text that were found that were just totally commonplace and totally misogynistic, and they would just reprint these ads for-- Then no comment.

As a whole, it's so incredible to see, especially with this hindsight, you think, I can't believe that they advertised. I think there was one where there's a woman who's lying on a carpet and has a man's foot on her head, and they're saying, "Nice to have a woman around the house." Things like that that are just so-- or women being slapped, and then they make some joke about domestic violence.

Alison Stewart: "Nice to beat your woman in bowling." That was it?

Cecilia Aldarondo: Yes, it was, "Beat your wife tonight," actually. Absolutely. Things like that. There's something about that recontextualization that is political that I think did a lot of this consciousness raising that we're talking about.

Alison Stewart: Alice, in your section, I think it's Gloria Steiman saying that Ms. was a portable friend. I think she says it. Is she?

Alice Gu: "It's meant to be a portable friend." Excuse me. As Salima mentioned before Ms., there was-- We have to imagine, time travel back. This is before the Internet. Now there's so much sharing of information with social media that people don't have to feel alone, and they don't have to feel crazy. Travel back 50 years, and there are women who were suffering silently, and they didn't talk. They didn't talk about whether their partners, husbands, were beating them. They didn't talk about whether they were being sexually harassed in the workplace. They quietly suffered alone.

It was because of Ms. and this Dear Ms. and the letter writing that women felt like they had a friend, and they found out for the first time through other letters and other women around the country that they weren't alone, and they weren't crazy. I just thought that was so profound, I couldn't even imagine. I'm so fortunate to have not grown up in that era that I-- I can't say that I never feel alone nor crazy, [crosstalk] not in the same sense I feel like that these women may have felt back in the '70s and before that.

Alison Stewart: We're talking about the new documentary, Dear Ms.: A Revolution in Print. Let's take a couple of calls. This is Marjorie calling from Nantucket. Hi Marjorie, thanks for making the time to call All Of It.

Marjorie: Hi there. Thanks for taking my call. I wanted to say that my mom was an ardent reader, supporter of Ms. from the very first issue. Starting at age nine, so was I. It was fabulous because it gave me a whole lot of information that wasn't available to most young girls, teenagers. From it, from some of the information I got from reading Ms., I was really well informed beyond the-- I had really good sex ed in school, but we were lucky. I was better informed than all my peers.

When I hit college and was looking for birth control, I was able to actually go in knowledgeable, ask for a cervical cap, which was not yet approved yet, become part of the study, and get them approved. It was all because of Ms. I had this great access to knowledge girls didn't have.

Alison Stewart: That is such a great comment, Marjorie. Thank you so much for calling us. Let's talk to Susanna, who's calling in from Westfield, New Jersey. Hi Susanna, thanks for making the time to call All Of It.

Susanna: Hi. I was 16 years old in around 1976, '77, when my father, who was a college professor, came home and handed me a Ms. Magazine, and I went on to subscribe to it. It was really life-changing and transformative for me because while my home was not sexist, I wouldn't say, there were a lot of assumptions made about girls and women in the 1970s, and I was a regular reader of Seventeen Magazine and was learning about how to do my hair. Then here's this magazine that's talking about sexual harassment, workplace discrimination, relationships, and power dynamics.

The no comment section was my favorite because I would see these outrageous classified ads that were blatantly misogynist. It really shaped me fundamentally. Like your previous caller, I felt like I was better armed and prepared and informed. When I went to college and as a young woman in my 20s, it made an enormous difference to me, and I subscribed for many, many, many years and was very sad when it finally closed down.

Alison Stewart: Thank you so much for making the call.

Cecilia Aldarondo: It didn't close down.

Alison Stewart: It didn't close down is what our producers are saying.

Cecilia Aldarondo: It's still in print.

Alison Stewart: Explain why she thinks it might have closed down.

Cecilia Aldarondo: I think part of this is the digital era that we're in and the way that publishing has been affected by that. Ms. is very much still in circulation, so you can resubscribe to Ms. You can go and read it right now. Just literally Google Ms. Magazine and you'll find it.

Alison Stewart: There's a clip Salima in your part about Harry Reasoner.

Salima Koroma: Yes.

Alison Stewart: Calling for Ms. Magazine, it says, in another tradition of American shock magazines. He said, "I give it six months and then it sold out." Harry Reasoner, of course, he didn't like it. I'm curious, where did you find skepticism or resistance to the magazine that surprised you?

Salima Koroma: You had the Harry Reasoners, and I actually was surprised by other women. For example, my part talks a lot about how Black women were involved in Ms. Magazine, or how they were not involved and excluded. I was very surprised to see this pushback from Black women who said, yes, Ms. Magazine was inclusive and it was for women, but it wasn't everything that we wanted. There's this tension between Ms. Magazine being a place for Black women to see themselves inside the magazine, not on the cover of the magazine.

I felt some pushback. When I was interviewing some of these women, I spoke with Michelle Wallace, who is a Black writer, who said she had never gotten that recognition for her work, but she also didn't see herself. I got pushback from other women. I thought that was surprising.

Alison Stewart: Alice, you heard in that call, the woman, I think it was Susanna, said her dad brought her Ms. Magazine, and that became an issue a little bit about who is the magazine for, because they did a men's issue, and some women weren't that happy that they did a men's issue. How did Ms. think about their male readers? Did they think about their male readers? Was this a one-off, the cover with Robert Redford on the front?

Alice Gu: I think they did a focus group, I believe, with women, and overwhelmingly many women said that they wanted an issue about men, because like it or not, men are part of our lives. They're our fathers, they're our brothers, they're our husbands, they are our sons. They are uncles. They're everywhere. The issue, I was so happy to hear about that previous caller, that her father had bought her the issue, because there was a lot of resistance. We were just speaking earlier. I feature Alan Alda in my section, who was one of the biggest stars of the time. He was one of the first, or probably the first, famous male celebrity to speak out for women.

He got a lot of heat for it. That was not appreciated. He was called the king of wimps. It really just showcases what a time this was. What I also wanted to show on my part, though, is I think that there was maybe a popular notion that to be a feminist meant that you hated men. I really wanted to show that that was not the case. These are women who loved their men, but they wanted their men to love them back and respect them in a way that society was-- we were moving to new ideas.

Alison Stewart: I'm speaking with directors Salima Koroma, Cecilia Aldorando, and Alice Gu. Their new documentary, Dear Ms.: A Revolution in Print, is streaming at Tribeca this week. It'll be on HBO later this summer. We are taking your calls. Have you ever been a Ms. Magazine subscriber? Tell us about your relationship with the magazine. Our number is 212-433-WNYC. 212-433-9692. We'll have more after a quick break. This is All Of It.

[music]

Alison Stewart: You are listening to All Of It on WNYC. I'm Alison Stewart. I'm speaking to the directors of a new documentary, Dear Ms.: A Revolution in Print. It's streaming at Tribeca this week and will be on HBO later this summer. Cecilia, your part of the documentary focuses on sex and pornography. It's had the anti pornography feminists and the anti-censorship feminists, and sex work activists. Where did the magazine find itself?

Cecilia Aldarondo: Smack in the middle. I think this is one of the things when we first were all brought into the project, we were asked to do our homework. We did our own research on the history of Ms., and really delved-- Part of the brief also was for us to select iconic covers that we were drawn to and center the magazine almost as a protagonist in the film. With that, we were given a lot of freedom. As I was doing all this research, I found out that one of my personal feminist icons, a woman named Annie Sprinkle, who, if you know the history of sex positivity, you've probably heard of her, had protested outside of Ms. in 1978.

Actually, our producer, Will Ventura, showed me this photo, and I said, "Wow, that's interesting. I had no idea." Then I was also reading about how this one cover in 1985, which attempted to bring all of these warring feminists into one room together, was-- The woman who wrote it said, Mary Kay Blakely, said afterwards it was the hardest article she ever had to write. Basically, Ms., the porn wars, as they're called, really divided the feminist movement in a very profound way and to this day continue to divide feminists.

It was ugly. Ms., to its credit, really, I think, frequently tried to facilitate debate and not necessarily only have one strident position on one thing or another, but they also didn't get it right all the time. In this case, they left out the perspectives of sex workers, women who were actually working in the industry. That's what I tried to draw attention to.

Alison Stewart: Yet there's one sex worker who said, like, they were very condescending towards her, and that seemed to be an issue.

Cecilia Aldarondo: Yes, I think you're dealing with respectability, especially we have the history of treating women in that work as fallen women and as much as we might think we're not in the 19th century anymore, I think that that way of thinking about women who actually choose this work and do not necessarily feel victimized to actually center their perspectives is something that I think was hard to do.

Alison Stewart: Let's take another call. This is Pamela calling in from Clark, New Jersey. Hi, Pamela. Thank you for calling All Of It.

Pamela: You're welcome. I love your show. The reason I'm calling is that I was in law School in 1972, and in early 1972, I subscribed to Ms. Magazine and continued. My contemporaries had all been socialized in a totally different way, or most of us, and yet we'd found our way to law school. Having Ms. Magazine was like a shot of adrenaline for us and an affirmation that we were doing something that was the right thing for women to do, because we were trying to overcome socialization. I was, of course, in particular, trying to overcome the way we'd been socialized. Any support we could have was really helpful.

We were supportive of one another during that period of time because there were not that many women in law school, and only 10% of the lawyers in the country were women. Thank you to Ms. Magazine, and I'm so glad this documentary is coming out so that during this time when there's so much repression, women will feel like they're part of a whole continuum of women who are determined to protect our rights, to have a full life.

Alison Stewart: Pamela, thank you so much for calling in. This text says, "I'm 66 years old and the great-grandchild of a suffragist, my mom, Bart, miss starting with the very first issue." Thanks to you for texting in about that message. For the documentary, this is for all of you. You spoke to Gloria Steinem and other founding editors of the magazine. We hear them express pride, sometimes we hear them express regret over things they could have done or should have done. Each of you, what stood out to you about the way that they saw their track record? We'll start with you.

Salima Koroma: My part deals with the beginning of Ms. Magazine, including that preview issue, which I think is such a wonderful issue. It shows the joy and the optimism that the magazine wanted to go into the future with. I spoke about that tension of putting a Black woman on the cover. That's something that my part also talks about. From the outside, I think, well, why couldn't more Black women be on the cover, and something that Letty Cottin Pogrebin, who's one of the founders, talks about is, "Well, if you put a Black woman on the cover in the south, they don't sell the magazines if a Black woman is on the cover, so how do you sell a magazine that is not making a lot of money and women are taking these pay cuts to write, and then how do you deal with that?"

I thought that was so fascinating, the tension between making money and having to actually support this business, and then telling all the stories of women. I thought that was so interesting.

Alison Stewart: That was Salima, by the way. Alice, how about you?

Alice Gu: In my part, I deal with, one of the covers is sexual harassment in the workplace. Another one is domestic violence, which shows a woman with a Black eye, a big bruise on her face on the cover. Pat Carbine, she recalled that cover. She says, "This cover is going to be the end of us." This was so controversial at the time. Their advertising department-- this was no enviable feat for them because they had that balance of wanting to tell the important stories, but it's still a business, and they want to be able to keep running.

To do that, they were dependent on the advertising dollars. They worked out of strong principle. Pat was like, "You know what? We have to do it, and we have to take the risk." There were advertisers that they lost entire years' worth of advertising for taking these risks. I really admire these women. That was a very difficult needle to thread. I think in the time they will leave some people out, they will anger some people, but they're trying to, again, no enviable task, to try and walk that middle ground where you try and do it all.

Alison Stewart: How about for you, Cecilia?

Cecilia Aldarondo: I want to pick up on something I'm hearing several of the callers bring up, which is the fact that this is an intergenerational project. We're all in similar ages. None of us were-- I was born in 1980 for reference. This is definitely like my mother's era of feminism. I think I just want to highlight for me, one of the things that was most beautiful about making this film was being able to sit at the knee of all these women and hear what they had to say, and to do my homework. I think that's something that we hope the film will encourage people to do.

I also just want to say that I think one of the things that really struck me about the Ms. staffers, the people that worked on the magazine, is that even when things were extremely divisive, like the porn wars, were called a war for a reason, even when people were really attached to their position, as a magazine, they tried to foster space for disagreement. That, I think, is really instructive.

Alison Stewart: We're going to get one call in. This is Tom Duane, former city council member and State Senator. Real quickly, Mr. Duane.

Tom Duane: Hi.

Alison Stewart: Hi.

Tom Duane: Hi. I was born in 1955, and I started college in, I guess, '72. I immediately started subscribing to Ms., because my whole life's political orientation had changed by then. I read Black Liberation, Women's Liberation, Queer Liberation books, and I also read Ms. Ms. was a magazine that I could get a tremendous amount of knowledge from, but I could also share it with my mother, who was Irish Catholic, not your typical Ms. reader. There were things in there that I could cut out and send to my mother.

Alison Stewart: Thank you so much for calling, Tom Duane. I've been speaking to Salima Koroma, Cecilia Aldorando, and Alice Gu. The name of their documentary is Dear Ms.: A Revolution in Print. Thanks for being with us.

Alice Gu: Thank you.

Salima Koroma: Thank you so much for having us.

Cecilia Aldarondo: Thank you. Thank you. Thank you.