Connie Chung on Her Trailblazing Life

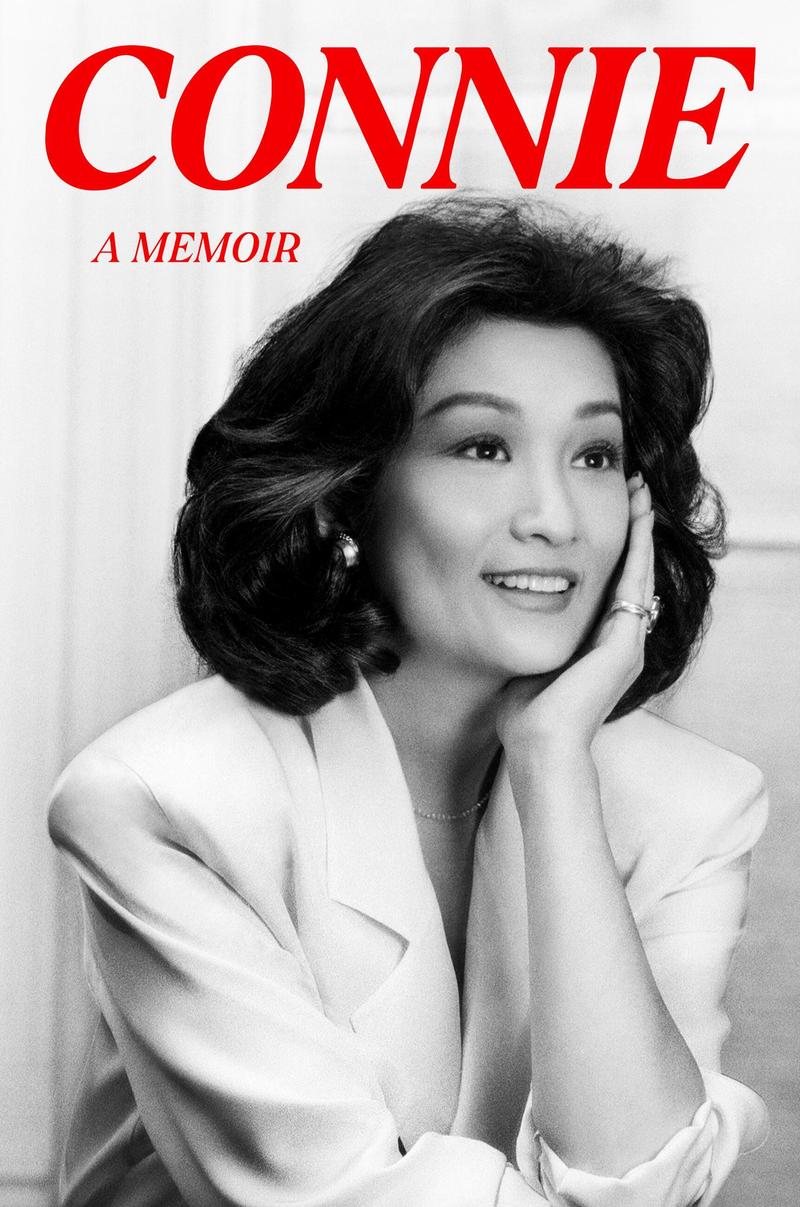

( Courtesy of Grand Central Publishing )

[MUSIC - Luscious Jackson: Citysong]

Alison Stewart: This is All Of It. I'm Alison Stewart, live from the WNYC studios in Soho. Thank you for sharing part of your day with us. I'm really grateful you're here. On today's show, musician Amethyst Kia has a new album out, and she's going to preview it for us with a live performance in WNYC studio five, and we'll talk about the new Broadway play production of The Hills of California with its star playwright and director. That's the plan, so let's get this hour started with the one and only Connie Chung.

[MUSIC - Curd Cuccini: Ice Dance]

Alison Stewart: In her new memoir, reporter and anchor Connie Chung wrote this about her early days in the news business. "Since I stood only five-foot-three-and-a-half inches, don't forget the half, I compensated by wearing stilettos. I wanted to be as close as I could be, eye to eye with the men. I did not want to look up at them. I wanted to be their equal." Connie Chung did that and a whole lot more. She was the first asian anchor of a major newscast and the second woman to do so. She was smart and assertive, like in this 1990 interview with then real estate developer Donald Trump.

Donald Trump: I sell very great condominiums in New York. I have the best casinos in the world.

Connie Chung: They aren't that great. Come on.

Donald Trump: They're the best. What, the Trump Tower?

Connie Chung: They're not the best. Maybe if you can try and answer this question without giving me the normal spiel. Huh?

Donald Trump: What is the normal spiel? I don't know-- [crosstalk]

Connie Chung: Well, the normal spiel is the fact is that many rich and powerful people do try to remain anonymous, but you became very public very clearly by your own design.

Donald Trump: I don't know if it was by my own design.

Connie Chung: You mean the publicity?

Donald Trump: I do developments which get a lot of publicity. I mean, if I didn't do Trump-- [crosstalk]

Connie Chung: Come on.

Donald Trump: I mean this. If Trump Tower weren't a great building on Fifth Avenue and 57th street by a young guy-- [crosstalk]

Connie Chung: Trump tower is one building in New York City with zillions of buildings.

Alison Stewart: It wasn't easy. She broke the mold for women of color during a time when it was one kind of white man filling the newsrooms. The 10th child of chinese immigrants who grew up mostly in DC, she started news by walking into a local newsroom and said, "I don't have any experience, but I'm a fast learner." Connie Chung has inspired many journalists, and she discovered her impact when she learned that Chinese American girls are named Connie after her. They're called Generation Connie. We will ask her about all of it. Connie Chung, welcome to the show.

Connie Chung: AlisonStewart, I'm a fan girl.

Alison Stewart: Aw, thanks.

Connie Chung: Didn't we cross paths at ABC?

Alison Stewart: At ABC and MSNBC.

Connie Chung: Oh, there you go.

Alison Stewart: At both places.

Connie Chung: There you go. Because you've been very peripatetic. You have gone here and there just like I did.

Alison Stewart: Yes.

Connie Chung: I see up here that you have a little sign that says, work hard and be nice to people, and I couldn't agree with you more.

Alison Stewart: Yes.

Connie Chung: Yes. There are a lot of people in our business, Allison, who were not nice.

Alison Stewart: We know that. We know that.

Connie Chung: I think that's why we cut out sometimes from one place to another, because we didn't want to work with a-holes, if you would.

Alison Stewart: Yes. That glass ceiling gets hard on the head-

Connie Chung: Yes. [laughs]

Alison Stewart: - so you move someplace else.

[laughter]

Connie Chung: Can I just ask you one question?

Alison Stewart: Sure.

Connie Chung: Do you miss television, because you're such a pretty girl-

Alison Stewart: Oh, thank you.

Connie Chung: - and you're so appealing on television, but do you prefer radio?

Alison Stewart: I love radio. I started in radio in college.

Connie Chung: Yes.

Alison Stewart: It gives me amount of freedom. I like the people I work with. It's a good place. It's a good thing.

Connie Chung: That's wonderful. I see you have a female engineer-

Alison Stewart: Yes.

Connie Chung: - and she's having a little munchy right now.

Alison Stewart: [unintelligible 00:03:52] sometimes. She works back to back shows. She's got to eat.

Connie Chung: Yes, I understand.

Alison Stewart: Gotta eat, Julianna.

[laughter]

Alison Stewart: When you reread your book, after finishing it all and you had to go back and reread it, what did you learn about your life? After recounting your life, what did you learn about you?

Connie Chung: Oh, really zeroed in on a good question. I realized that I wasn't a big, gigantic, chop liver failure in many ways. I always thought, "Oh, I screwed this up, I screwed that up," because I've always been a shoulda, woulda, coulda person. Then, I thought, "Okay, this wasn't bad, that wasn't bad," but there were loads of doubts, and actually, reliving it was good for me. My nephew said to me, was it cathartic? I thought, "Let me look up catharsis," just to be sure so that I could answer him accurately.

The original definition was medical, which was expunging your bowels of-

Alison Stewart: Stuff.

Connie Chung: Yes, stuff. Unwanted material. I found that when I did, I really got rid of a lot of stuff that had been sitting in my body for so long that it was actually pretty good. Expunging my body of things that I really wanted to get rid of but had a hard time-- I kept holding onto it.

Alison Stewart: Your book goes into detail about your parents, about your family. Your parents were an arranged marriage. They had ten kids in the household, some of whom died very young. What kept them together as a couple?

Connie Chung: Just tradition. Honestly, I don't even believe in any way, shape, or form that love was there, because they were forced to be married, engaged at 12 and 14, and then married at 17 and 19. They were thrown together the way arranged marriages are. In that incredibly traditional way, they stuck together the whole time and they bonded, but I don't think it was a very personal, emotional relationship. It was emotional in the bad sense, actually, because I think given a choice, they would not have stayed together.

My father would always say, "Can you imagine being stuck with someone that you didn't love?" My mother just wouldn't talk about it. She was just-- She just wouldn't go there.

Alison Stewart: Your family's story is like a lot of Americans, they came to the country as immigrants. You were born here, though.

Connie Chung: Yes.

Alison Stewart: What do you want people to understand about immigrants and migrants who come to this country? When you're watching a story, what are you thinking about them? What do you want people to know about them?

Connie Chung: Everyone has a story to tell, and they just want to assimilate. That's what all of us want, is just to be just like everybody else and not be considered a foreign. Yet, at the same time, I mean, like my sisters, my four older sisters who were all born in China, all they wanted to be was American. I was a peculiar animal in that since the rest of the family was born in China, I wanted to be like them, be born in China too, because I thought that being born in the United States meant that I was different from them, and I wanted to be just like them.

Every person who came to the United States can look back in their history, and they came from some other country. When people look at us and see race on our face, it's a look that we recognize and we don't really appreciate because they will-- People have said to me, "Where are you from?" I say, "Washington, DC." That's where I was born. Then, "No, where are you really from?" I know they mean China. I think it's disconcerting not to be accepted. I lived my life not believing that I was accepted. To this day, it still happens. It really does.

Alison Stewart: Wow.

Connie Chung: Just the other day, some people were looking at me, didn't address me because they thought that I was, I don't know, couldn't speak English, really, and they were addressing people who were white Americans. It's disconcerting. It's like, "Excuse me, I'm here." I happen to be the matriarch of this family.

Alison Stewart: [chuckles] My guest is Connie Chung. The name of her book is Connie: A memoir. You spent a little time in Texas but most of the time in DC. What was high school Connie like?

Connie Chung: Well, I was a head on a stick. Really, really skinny. I mean, I think, looking back, that I looked kind of anorexic. It's not that I was trying to be, it's just that I was so darn skinny. Really, the head was the only thing that was bobbing around. Everything else didn't move because it was sticking to my bones. [chuckles] I was so on the fringe. In other words, I wanted to be part of the in crowd, but I couldn't possibly being a head on a stick, while everybody else, all the girls were developing beautiful twins on their chests, a pair of soft twins, and I was going, "What happened?"

I was having an inversion layer. They were going inward, not outward. I thought, "This is not right." What my sisters used to say is, "What God has forgotten, we fill it with cotton." [laughs]

Alison Stewart: Well done. Well done.

Connie Chung: Only one sister had actual boobs. I used to creep up behind her when she was brushing her teeth, leaning over and brushing her teeth, and I'd try to pump them like a cow, like milking a cow. She [unintelligible 00:11:40] "Get out of here." She was so proud that she had twins and none of us did. It was-- [crosstalk]

Alison Stewart: Were you interested in school or were you just interested in-- [crosstalk]

Connie Chung: Having a body?

Alison Stewart: Yes.

Connie Chung: No, I wasn't that superficial. I actually did make good grades. Fairly good grades. I was good in science, and typical chinese person, math, science, really, really good. You know what I did, Allison, to sort of make my mark? I ran for student government, and that got me to overcome my basic shyness and being a little bold. I didn't want to be secretary or treasurer because secretary pigeonholed me in a woman's thing, and treasurer, I just-- I don't know.

I couldn't be president because girls just weren't president, so I was vice president of junior class.

Alison Stewart: I love the story about how you went into a local newsroom, you didn't know anybody, but you found the news director and you said, I'm your girl. What was your pitch to this guy?

Connie Chung: Oh, yes, "I don't know anything. I have never had a job in news, and I'm very, very inexperienced. I'm green as heck, but I learn fast and I have a lot of energy, and I will be very dedicated, so you really do want to hire me. I'll come two days a week. If you can't pay me, I'll volunteer." It was a good bit of advice that I got from one of my professors at school. He said, "Get a job the semester before you graduate and just volunteer two days a week, or get paid nothing two days a week, and that way, your foot will be in the door while everybody else is knocking on the door in June."

It was great advice because I was sitting in there and people were knocking the door down. The problem is you can't barge into a newsroom today. I'd get arrested. You'd get arrested. We'd all get arrested. I couldn't even get in this building without your person meeting-- [crosstalk]

Alison Stewart: Showing you upstairs.

Connie Chung: Yes.

Alison Stewart: It was so interesting, your decision that you were going to be like the male reporters. You were going to walk around like one of the male anchors. What did that look like? Did you believe it or were you faking it till you make it?

Connie Chung: [chuckles] Pretty cool. I could see as I looked around me, it was all men. There was one Black guy and one woman who was primarily a radio reporter. When I saw all these men and my competitors were all men and the people at coverage were all men on Capitol Hill, White House, Pentagon, state department, I said, "I'm going to really take on their characteristics. I will have bravado. I will have moxie. I will stand tall."

Even though I was wearing a miniskirt and stilettos and they were wearing these stayed boring suits with ties and button down shirts and wingtip shoes, I would walk around like I was just one of them. The worst thing I did, but effective, was I had a potty mouth. That really threw them off their skids. I mean, off their track, because here I was, this little lotus blossom, and I had a trashy mouth, and they couldn't quite get their arms around it because it just didn't fit.

Since they were throwing F bombs around, I thought, why can't I? It just made no sense that if they were throwing sexual innuendos at me with words that most people wouldn't use, I could do it too. What was keeping me back from it? I really was so convinced I was a man. As I say in the book, when I walked past a mirror, I jump because I'd see a Chinese woman staring back at me and I'd say, what the?

Alison Stewart: [unintelligible 00:16:27] It's interesting that you pointed out the sign, work hard and be nice to people, because in your book, you have an encounter with Barbara Walters early on, and I thought was really interesting because you saw her talking abruptly to her assistant, and you wrote, "I was taken aback. Barbara seemed so businesslike, responding in a rat-a-tat rhythm, 'Yes. No. Next.' It was like a scene from an old Rosalind Russell or Bette Davis movie, a woman executive barking orders to an underling. I thought to myself, if I ever get to that point in my career, I'm going to throw in a lot of pleases and thank yous."

Connie Chung: Yes.

Alison Stewart: Why does that matter to you?

Connie Chung: I have a big problem with people in our business, and I'm talking about television in particular, they have these delusions that everybody knows their names, that they engage in such self aggrandizing behavior. My husband and I-- you know Maury Povich?

Alison Stewart: Do know Maury. Yes.

Connie Chung: He's been determining the paternity of every child in America, but I can assure you, Allison, he has a bigger vocabulary than you are the father and you are not the father. One of his greatest characteristics is that he does not take himself seriously, and he's always told me that, "Take your work seriously, but don't take yourself seriously, and don't take your critics seriously. Just take your work seriously." He's seven years older than I am, but he's also in journalism, and he started out in journalism, and then he determined whether people were the baby daddy or not, but he's really nice to people.

I have always felt that I'm one of the grunts, and there's no such thing as stardom and stuff like that. I can't help myself from being a bit Mother Teresa-ish, and my husband keeps saying, "You go overboard," and be nice to people, but it's my nature. I don't know why other people can't do it. It's pretty easy to be nice, and they have this propensity to be rude. I can't imagine people who are not nice. It-- [crosstalk]

Alison Stewart: I know. It's odd to me.

Connie Chung: Really, right.

Alison Stewart: It is very odd to me. I mean, there's so many times that sometimes you have to be tough or you have to be difficult because the situation calls for it.

Connie Chung: Yes.

Alison Stewart: Why not be nice when you can be?

Connie Chung: Yes.

Alison Stewart: Right?

Connie Chung: Yes, exactly. I don't know. Life is short.

Alison Stewart: Yes.

Connie Chung: What does it take to say thank you and please and not be obnoxious? Unless you happen to really be an obnoxious person.

Alison Stewart: My guest is Connie Chung. The name of her memoir is Connie. Every reporter tells a story because it has meaning to them. You could talk about the Oklahoma City bombing, you could talk about your interview with the captain of the Valdez, HIV-infected Magic Johnson. What is the story that still means something to you that you still think about that you did?

Connie Chung: I think it's Watergate. It was the story of the decade, and we never thought that we would see anything like that again. Everyone rose to the occasion. The Republicans joined the Democrats in realizing that wrong was committed by their president. Even the staunchest of conservatives, Barry Goldwater, according to Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein, went to the president and said, "You're going to be convicted of impeachment if you don't resign." The shocking thing today is that that kind of clear thinking and integrity no longer exists on Capitol Hill.

I look upon Watergate as a great lesson that the country learned and that Capitol Hill learned and the public learned, and yet it's as if it never happened because today we're facing an extraordinary situation in which integrity has fallen by the wayside in our government. It's shocking and depressing. I hate to bring us down like that.

Alison Stewart: No, it's okay. I mean, it is what it is at the moment. In the book, you talk about your own flaws, your own mistakes. You're very honest about them. You're honest about your time at CBS News co-anchoring with Dan Rather, and it was interesting because I got the feeling that Mr. Rather, he didn't have a problem with your gender or with your race, he simply wanted to anchor by himself.

Connie Chung: By himself. That's right.

Alison Stewart: When did you get the first inkling that, oh, this man wants to be alone.

Connie Chung: He wants to be alone. [laughs] The very first day after--

Alison Stewart: Oh wow.

Connie Chung: Yes, after it was announced, and I had no idea if he was told or he had a gun held to his head or what. I never found out because it was go from the moment they told me. He said, let's go have a cup of coffee at the corner dive. Great. Sure. Sat down, and he said, "You're going to have to start reading the newspaper now." I thought, "Really?" What I said in the book was that I thought that it was like that movie All About Eve, in which Bette Davis is climbing the stairs and she says-- [crosstalk]

Alison Stewart: Put on your seatbelt?

Connie Chung: Yes, "Put on your seatbelt. It's going to be a bumpy ride." I could tell this is going to be a rocky, rocky road, and it was. I thought, "I'll just do my job. I'll work hard. I'll take the AlisonStewart School of Journalism and I'll work hard and I'll be nice to people, but it was not to be because he really wanted to be solo. Having me as more like, to him, an appendage as opposed to a partner just didn't work. It was just like what Barbara Walters faced when she became co-anchor with Harry Reasoner.

Alison Stewart: Reasoner. What I thought was interesting in the book is how the women in the news business looked after one another, even the toughest women, even the women who maybe you were in competition with. Why do you think you all did that?

Connie Chung: I think we knew. We knew that we were such a minority, but the problem was we were given such a tiny sliver of the pie, and the men got to share the whole rest of the pie. That was simply what happened back then. Now women have a bigger slice of the pie, but still not any level of parity. I found that because we had to share a really skinny sliver of apple pie, there were women who were still competing with each other, which was not healthy because the men were competing with each other, too.

In fact, Allison, I gotta tell you. When I was out, [laughs]-- See how cute you are?

Alison Stewart: Oh, yes. Tell me more.

Connie Chung: Nobody can see your gigantic smile and your eyes bucking out and your reaction, whereas on television, they can. Unfortunately, they can't see you.

Alison Stewart: Tell me my story. I want to hear my story.

[laughter]

Connie Chung: Okay. There were all three anchormen. Tom Brokaw, Dan Rather, and Peter Jennings were speaking at different times before this particular group, and the woman who was in charge said that all of them individually wanted to know how big the other one's crowd was. Please, right. It happened to be there were two other women speaking around the same time, too. They never cared about how many. It's sort of like crowd size with Trump. [chuckles] How many people were there?

Alison Stewart: Connie, we have run out of time. I could talk to you for the rest of the hour.

Connie Chung: Oh.

Alison Stewart: We'll figure it out. We'll figure out a time to talk and have real talk.

Connie Chung: Okay. Allison, you won't consider doing television because you're done with television.

Alison Stewart: I like the radio.

Connie Chung: Yes.

Alison Stewart: I like the radio.

Connie Chung: Good for you. Seriously, that means you don't have those self-aggrandizing characteristics that anchormen do.

Alison Stewart: [laughs] Connie Chung has written a memoir. It's called Connie: A Memoir. Thank you so much for taking the time today.

Connie Chung: Thank you for letting me. I'm a fan girl, you know that. I mean, now you know, and I'm just thrilled to meet you.