Celebrating the 100 Year History of 'The New Yorker'

Alison Stewart: This is All Of It. I'm Alison Stewart live from the WNYC Studios in Soho. Thank you for spending part of your day with us. I am grateful you are here. On today's show, we'll talk to documentary filmmaker Kayla Johnson about her new film Fatherless no More about a program at Rikers Island. Caroline Weaver, AKA The Locavore, is here to tell us where we can shop locally in Brooklyn, and New York Cares executive director will join us to share ways to give back this holiday season. That's the plan so let's get this started with a big birthday. This year The New Yorker turned 100 years old. The magazine was founded in 1925 by Harold Ross and Jane Grant.

It has spent the last century shaping culture, spotlighting great fiction, providing a space for long form journalism, and of course, there's everyone's favorite, the cartoons. The new Netflix documentary, directed by Marshall Curry, takes viewers behind the scenes at The New Yorker as it prepares to release the centennial edition of the magazine. It was the 5,057th issue. The film travels back in time to significant pieces throughout The New Yorker's history like Rachel Carson's Silent Spring, Truman Capote's In Cold Blood, and James Baldwin's letter From a Region in My Mind. You can stream The New Yorker at 100 now on Netflix, and I'm joined now by Oscar winning director Marshall Curry. It is really nice to meet you.

Marshall Curry: Well, it's great to be here. Thank you so much.

Alison Stewart: Listeners, let's get you in on this conversation. We are taking your calls. What is your favorite piece from The New Yorker, or your favorite cover, or your favorite cartoon? We want to hear what The New Yorker means to you as they celebrate their 100th birthday. Our phone number is 212-433-9692, 212-433-WNYC. You can call in and join Marshall on the air, or you can text to us at that number as well. 212-433-9692. What is your earliest memory of The New Yorker?

Marshall Curry: I grew up in a house that got The New Yorker and as a kid I was always a little intimidated by it. I would be attracted by the covers and I would flip through and look at the cartoons and half of them I understood and eventually got a little older and understood more cartoons and then started reading The Talk of the Town, the short pieces at the front and eventually graduated to the 10,000 and 20,000-word huge tomes that they publish in there sometimes. When I got to my 20s, I got my own subscription, and I've been a huge fan ever since.

Alison Stewart: Yes, I can remember when I first came to New York in '88 and getting The New Yorker, is what you kept in your backpack for the subway ride.

Marshall Curry: That's right.

Alison Stewart: When you sat down to think about this film and what you wanted to accomplish, what did you ultimately want to accomplish? What was in the edit room [laughs] wall which you have to go back to every time?

Marshall Curry: The huge challenge of making this film when we first decided to approach it was how do you get an institution like The New Yorker that has so many different kinds of writing, so many different illustrations, to cartoons, politics, culture and 100 years of that into a 90-minute movie? I had somebody tell me that trying to make a 90-minute movie about The New Yorker was like trying to make a 90-minute movie about America. That was the big challenge, is how do we make choices that will give you a sense of this incredible institution, its changes and twists and turns over history, and also feel complete and entertaining, like a cinematic movie.

Alison Stewart: Let's start at the beginning. What were the original goals of The New Yorker when it was founded in 1925?

Marshall Curry: I didn't know the history at all when I started this project-

Alison Stewart: That must have been fun, though, to learn.

Marshall Curry: -so it was really fun. It really was and it was full of surprises to me. If you had asked me who the founder of The New Yorker was before I started this thing, I would have said, ah, probably some guy from the Upper East Side, a Princeton graduate who was part of the hoity toity New York City inner world. In fact, it was founded by a high school dropout from a mining town in Colorado who'd come to New York and wormed his way into the group of folks at the Algonquin Round Table, this group of smart, witty writers, and he and his wife were trying to come up with ideas for magazines.

He was a newspaper guy. The idea that they hatched was to make it a comic weekly. It was not going to be a serious journalistic magazine at all. It was going to be gags and funny cartoons and funny articles. It almost failed when it first came out. It was not a big seller until they finally published a story that was this saucy tell-all by a society insider about why we go to cabarets. That was one of the big hits of the magazine that kicked it off.

Alison Stewart: Let's take a call. This is Gayle calling in from Chelsea. Hi, Gayle. Thanks for calling All Of It. You're on the air. [silence] Is Gayle there? Hold on a second. Give us a minute. We'll find out a little bit more. What are some of the decisions that Harold Ross, this person who you've just described, and Jane Grant, it's her first husband, that's right, Jane Grant, her first husband, that they made together in the early days that still remain with the magazine?

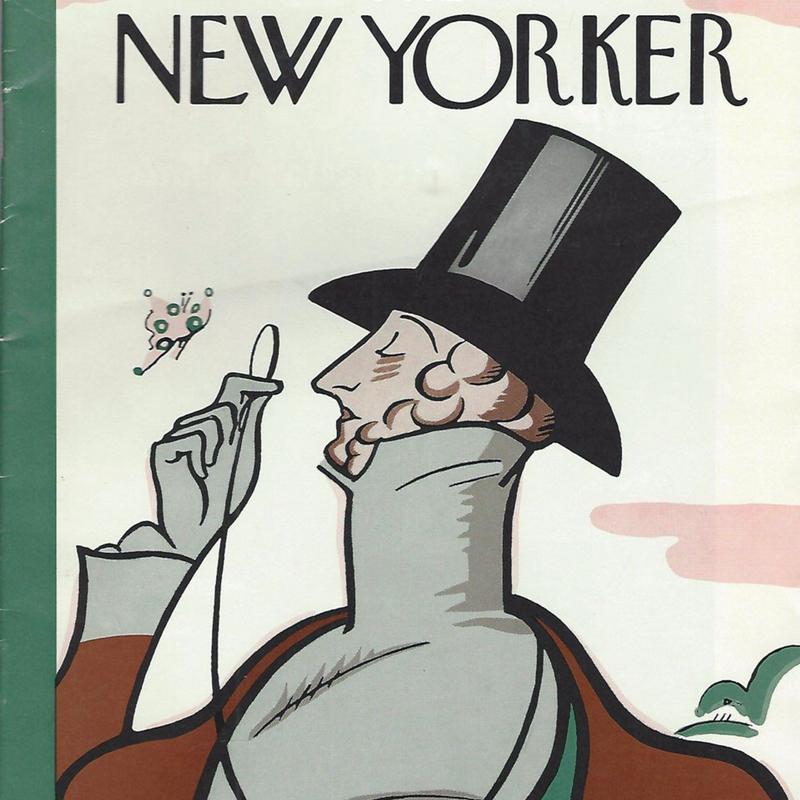

Marshall Curry: I think that sense of humor is something that is part of the magazine's DNA. It's well known for the comics today. Shouts and Murmurs is funny. There's just a sense of irreverence that is part of the magazine's style. Even in the serious articles, a lot of the writers have a funny, detached sense of humor about themselves and the magazine itself. The character on the cover of that first magazine was this guy named Eustace Tilly that they named, the guy with the top hat and the monocle looking at the butterfly.

Another thing that was interesting to me was discovering that that was a character that they thought was funny even in 1925. It was a spoof of the fusty fuddy duddies of 1925. We think, or I anyway thought when I see that character that that was The New Yorker taking itself seriously in 1925 but in fact it was a spoof comic character even then.

Alison Stewart: We are talking about the new documentary The New Yorker at 100. You can stream it now on Netflix. My guest is director Marshall Curry. Listeners, we want to hear from you. What is your favorite New Yorker piece, cover or cartoon from the last 100 years? Our phone number is 212-433-9692, 212-433-WNYC. Let's talk to Fran who is calling in from Lawrenceville, New Jersey. Thanks for taking the time to call All Of It, Fran.

Fran: Oh, thank you. Thank you for taking the call. My memory is Henry Martin's cartoons, which I always loved. I always thought they were so creative and funny and fast forward 30 or 40 years, and I went to work for Princeton University and find out that Henry Martin is an alum and had cartoons for reunions at Princeton and they were just great too. Also, find out his daughter Ann Martin wrote all the Babysitter Club books, which my daughter just loved and read I swear every single one. That's my memory.

Alison Stewart: Thanks so much for calling in. This text says, "The John Hersey Hiroshima piece issue, which has become a book, everyone should read it." This was a serious turning point for the magazine. World War II, it went from being sort of a cheeky magazine to being quite serious. How did it change tone?

Marshall Curry: That article really marked a turning point, as you say. There had been some serious articles that were finding their way into the magazine up until that point. When the atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima, the American government would not allow there to be any photographs published that showed suffering of Japanese civilians. The New Yorker decided to send a young writer, John Hersey, to Hiroshima. He wrote this incredible piece. I believe it's about 30,000-word piece. It was so powerful that they decided to turn the entire magazine over to that one article. There'd be no cartoons in it, there'd be no cheeky Talk of the Town pieces in the front. It was just going to be that one piece.

It marked a turning point both for the magazine, which suddenly began to be a real player in the global stage of serious journalism, but it was also a turn for journalism in general because the style of that piece was revolutionary. He went and found a number of Japanese civilians and wrote their story in this almost novelistic threaded story. It was not interviews with generals talking about how many TNTs equivalent the atomic bomb was or anything like that. It was individuals who were telling their personal stories of what they experienced and felt on that day, and written with this almost fictionalized style, even though it was factual. That really changed journalism as much as it changed The New Yorker. A lot of people saw that and began writing that way as well.

Alison Stewart: Yes, it's interesting. It changed from the who, what, where, when, to the why.

Marshall Curry: Exactly, and how did it feel.

Alison Stewart: And how did it feel.

Marshall Curry: Yes.

Alison Stewart: Let's talk to Charlotte in New Jersey. Hi, Charlotte, thanks for taking the time to call All Of It.

Charlotte: Hi. I just looked up the name of it because I couldn't remember what it was called. The three-part series by John McPhee called Assembling California. It was in 1992 and it was three parts, and it completely revolutionized everybody's thinking on how the Earth's crust was formed. That it was tectonic plates, not volcanic, pushing things up. It blew my mind. I couldn't believe it. It's probably the article that stayed with me, or articles, because it was three parts. It just changed everything. I thought The New Yorker changed everything. This is so cool. I'll never forget it.

Alison Stewart: Charlotte, thanks for calling in. Let's talk to Francine in Manhattan. Hi, Francine, what's on your mind?

Francine: Hi. I'm actually staring at my favorite New Yorker cartoon, which has been on my refrigerator for years, and it's by Paul Noth. There's two female doctors, one of whom is of color, and she's talking to an elderly white man's family outside his hospital room. The caption is, "We're doing everything we can to make him comfortable, short of dressing up as male doctors."

[laughter]

Alison Stewart: Thank you.

Francine: It just reminds me we've come far but we've still got more work to do.

Alison Stewart: We do. That's something that you address, Marshall, in the film. You talk about how there was racism in cartoons, especially. You look at the staff. There are reporters now but in the higher ranks it's still predominantly white. How did you want to address the history?

Marshall Curry: Well, I love The New Yorker and so I wanted the film to be a celebration of fact-based journalism but also, I'm a documentary filmmaker and I wanted to have a cool eyed look at the magazine and the magazine's history, and I think the film reflects that. For much of its tenure it was a white magazine written by white people for white people. I think it didn't live up to the standards that it holds itself to to today. One of the big turning points was the publication of James Baldwin's piece that really introduced a lot of people to the suffering and struggle and frustration that Black people were feeling in the 1960s and also helped change the magazine and, frankly, catapulted Baldwin into the limelight. He became a huge figure in part because of the story that he wrote.

Alison Stewart: Let's talk to Tracy in Queens. Hi, Tracy. Thanks for calling All Of It.

Tracy: Hi, how are you doing today?

Alison Stewart: Doing well.

Tracy: Good. I'm calling about a piece that was written, I believe, sometime in the '80s or early '90s. It was a piece about they had found a fragment of a bone in one of the Pacific islands. It was four articles in four different editions of the magazine. It was a forensic article, and it was just about how they were able to identify the pilots from the airplane and the other remains that they had found on this island from the World War II. It was very interesting.

Alison Stewart: Tracy, thank you so much for calling in. Hearing these calls about these different articles which meant so much to so many different people, it must have been hard.

[laughter]

It must have been incredibly hard for you as a documentary filmmaker what to highlight. I'm only going to ask you this. What's a story that ended up on the cutting room floor, one that you wish was hard?

Marshall Curry: There are so many historical stories that-- John McPhee isn't mentioned in our film. That's a tragedy. There was so much that we wanted-- Hannah Arendt coined the phrase "banality of evil" in The New Yorker magazine. I'm hesitant to tell you too many because people will start to think, wow.

Alison Stewart: Those are good examples, though.

Marshall Curry: I have felt this thing could be a Ken Burns eight-parter and it would not be boring. There's just so much to say.

Alison Stewart: We're talking about the new documentary The New Yorker at 100. You can stream it now on Netflix. My guest is director Marshall Curry. What were you excited to get access to as a filmmaker when you started to make the film?

Marshall Curry: As somebody who read The New Yorker, I was always interested in who these people are that are writing these pieces and how do they get written. That's the thing I love best about being a documentary filmmaker, is it gives you a license to be nosy and to ask people questions, sometimes personal questions about the things that are motivating them, sometimes thoughtful questions about the process of the work that they do, their craft, their approach to their craft, the ethical questions that they wrestle with as they're writing. Getting access to that many brilliant writers and cartoonists. We go home with Roz Chast and see her house.

It was also really fun to get to be in the offices themselves. A lot of the writing is done outside of the office but being in the office allowed us to watch the process of how cartoons are selected for the magazine. It allowed us to be there on election night when Trump was elected and to see how their political writers were covering that. That night they had a cover that they were prepared to run of Kamala Harris if she won, and some ideas of what they were going to run if Trump was elected. We meet with David Remnick, the editor of the magazine, and he explains the different approaches that they're going to take depending on the outcome of the election.

At that point, of course, nobody knew. As he says, we were at a hinge moment in our history, and we don't know what tonight is going to hold. When you get to witness moments like that and to see from the inside, how does a news magazine cover a moment like that, how do they handle a moment like that, that's the documentary goal that I love.

Alison Stewart: That was an interesting part in the film, because if Kamala Harris won, it was a much more hopeful cover, whereas the editions they had for Trump were darker.

Marshall Curry: They were.

Alison Stewart: That could be seen as political bias. That could be seen as truth telling. It tells a little bit about who their audience is maybe. Is it a magazine for a certain type of person?

Marshall Curry: I think it is, in a way, but maybe different than what you might think. If you asked David, he would say, "We are a magazine for people who are curious about lots of different kinds of things, who are willing to spend a lot of time going deeply into a complicated issue." They're not trying to compete with TikTok and Twitter. To that extent, it's a magazine for a particular kind of person.

I think they have one and a quarter million paid subscribers right now. I think there's 10 million people like that in America that they could reach. We touched on the fact that it had historically been a magazine for white people, by white people. The film asks a number of times through the film, is this an elitist magazine? What does it mean to be elitist? I think they would say it is a magazine for anyone who is curious, who's willing to engage with rich art, with complicated stories and nuance.

Alison Stewart: I thought, though, the cover thing was interesting, though, because there were a lot of people who voted for Trump and wouldn't have seen it as a dark time.

Marshall Curry: That's right.

Alison Stewart: That's what I thought was interesting.

Marshall Curry: It has a point of view. I don't think they would deny that it has a point of view. They want to explore complexity, even in politics. Andrew Morantz goes to a Trump rally, and he writes about it and says that he really wants to write the best version of that point of view. I don't think they want to set up strawmen and knock them down. They want to really engage. He wouldn't pretend that he has no preference between Trump and Kamala Harris. He just does.

I think that as a magazine, it's not trying to be a straight reporting of the news. It's engaging in a deep way with politics. The writers there have points of view. That's part of the reason that the magazine's so terrific, is that when they write a profile or when they write about the earth's crust, you can feel the writer, you can feel the specificity. It doesn't get sanded down into generic who, what, where, when reporting of facts. That's not what they're trying to compete with.

Alison Stewart: After the break, we'll talk about cartoons and a very important person, the office manager at The New Yorker. We'll have more after a quick break.

[music]

You are listening to All Of It on WNYC. I'm Alison Stewart. My guest is Marshall Curry. He is the director of a new documentary, The New Yorker at 100. You can stream it now on Netflix. It's The New Yorker's 100th birthday. Let's talk to Nikki in Irvington. Hi, Nikki. Thank you so much for making the time to call All Of It.

Nikki: Hi, thanks for taking my call. The New Yorker has been part of my life for more than 60 of the magazine's 100 years. My father subscribed. I loved the cartoons when I was a child, and I actually wanted to be a cartoonist. My mother-in-law papered her bathrooms with New Yorker covers. One that I remember the most is from the 1950s and it could apply today. It's a wealthy man standing in his luxurious backyard garden with a fountain and he's looking over the hill and there comes a bulldozer about to develop his next-door property. The covers, the cartoons are just such an important part of my life now. Now my daughter subscribes, so it's a multi-generational pleasure.

Alison Stewart: Thank you so much for calling. Let's talk to George who is calling in from Newark. George, you're on the air.

George: Hi. Thank you. Two things. I have a favorite cartoon and I have a question as well for the speaker. My favorite cartoon was in the '70s when New York was suffering a very hardship financially and a bad rap from the rest of the country. It was a cartoon of a very successful corporate businessman, suit, umbrella, newspaper under his arm, briefcase, talking with a tourist family with the flowered shirts and the pendants and the camera and the caption read, "Yes, it is a nice place to visit, but I wouldn't want you to live here."

[laughter]

Alison Stewart: Thank you so much for calling in. You know what, what is the history of the cartoons, Marshall?

Marshall Curry: Well, there've been cartoons since the very beginning. The process where they select the cartoons was a really fun thing. They get probably 1,500 cartoons every week that are submitted. Many of them come from regular cartoon artists but a lot of them come in over the transom, just completely unknown people who submit their cartoons, and they all get looked at. The cartoon editor and her team narrow that 1,500 down to about 50.

Then there's this fun meeting where David the editor and the cartoon editor and a couple of other staffers get together in a room and David flips through the 50 that she's selected, and he has three baskets. One that says 'yes', one that says 'no', and one that says 'maybe'. He checks them out. When they make him laugh, he puts them in the yes pile, and they get into the magazine. If they're not, if they fall flat, they go in the no. If you can't decide, they go in the maybe.

Alison Stewart: This text says, "I taught an illustration class at a small art college for years. For the final project, I assigned a topic on current events and had students create a New Yorker cover. They loved it and had some really clever ideas."

Marshall Curry: My daughter is in college, and she has the covers up on her wall over her bed. I think that is one of the things that makes The New Yorker distinct from so many other terrific magazines that I've loved through the years is The New Yorker is unlike Life and Time and Newsweek and US News & World Report. It's something that you can pick up 5 years later, 20 years later, and still find that article about the earth's crust or the forensic bone study that people are calling, or a cartoon or a cover that still lasts this many years later.

Alison Stewart: One person I wanted to spotlight is the office manager, Bruce. He's been with the magazine since 1978. What did he tell you about The New Yorker that probably no one else knows?

Marshall Curry: He's terrific. I loved getting to know him. He has been at The New Yorker for the tenure of four of the five editors. He is the person who has seen the most probably. He also was the person who saved so many of the artifacts. When they moved their offices the first time, there were boxes of things that were going to be tossed into the trash that he grabbed and held onto and now have been preserved, old drafts of articles and objects that were going to be tossed away.

He also was the deliverer of a piece of gold, which one day he came up and said, "I just got a videotape that somebody had a video camera and walked around the office, one of our earliest offices, and just pointed the camera at the offices, pointed the camera at people, and captured the feeling of the magazine at that point." Now, of course, it's in the World Trade Center, and the offices are pretty gleaming and big windows. At that point, it was dusty sofas that would poof with dust when you sat down. You can just see these piles of paper everywhere. He said it smelled like cigarette smoke. You can see people smoking cigarettes at their desks. It's a real time capsule into what life at The New Yorker was like back then.

Alison Stewart: Let's talk to Kathy in Astoria. Hi, Kathy, you're on All Of It.

Kathy: Hi. Thank you for taking my call. I wanted to share. About 20 years ago, I was at my husband's family reunion and there was a snafu with the hotel and all of my in-laws had to share one hotel room. That night when everyone was trying to fall asleep, someone started reading this Shouts and Murmurs piece aloud called The Ambien Cookbook. It was, I think, published in 2007, and it featured recipes like tummy cake and licorice surprise, which was about eating a electric blanket in the middle of the night. Everyone laughed so hard and for so long that it's now become a tradition at every family reunion that we have the reading of The Ambien Cookbook.

Marshall Curry: That's great.

Alison Stewart: Thanks so much for calling. Colleen in Tewksbury. Hi, Colleen. You're on the air.

Colleen: Hi. Hi. Oh, thank you so much for making this documentary. I can't wait to see it on Netflix. The omission of John McPhee is sad but understood. The first thing that comes to my mind on this entire conversation is a cartoon. Sadly, I cannot recall the creator of this cartoon, but it has become my go to response in so many circumstances. I'm at a loss for the actual words so I've bastardized it over the years. I'm hoping that you will have some recall and be able to help me identify it. Specifically, it's a cartoon of a gentleman businessman at his desk with his open book calendar. He's on the phone scheduling an appointment. The words are something to the effect of, "That is a week from never found." Obviously, the implication is that he really doesn't want to schedule this appointment.

Marshall Curry: I think that line, I think he says, "How about never? Is never good for you?"

Alison Stewart: [laughs] That's a good one.

Marshall Curry: I think that's what it was. That's a terrific one.

Alison Stewart: There have been five editors-in-chief of The New Yorker: Harold Ross, William Shawn, Robert Gottlieb, Tina Brown, and since 1998, David Remnick. What sense did you get from this documentary about the role of the editor-in-chief in making and shaping the magazine?

Marshall Curry: I think each of those editors really made a huge mark on the trajectory of the magazine. The first editor that we mentioned earlier was this rough around the edges chain smoker, as I said, a high school dropout but obsessed newspaper man who wanted every word and every fact to be right. He was the one who had founded it to be a comic weekly but he also was the one who ran that Hersey article about Hiroshima. The second editor was the one who really got the magazine to be a little bit more political, significantly more political, and he embraced some of the more serious articles. He was there for quite a while. The articles were long and in depth.

Today, of course, you have David Remnick, who's been the editor for quite a few years. People say that he brought politics and current events to the fore of the magazine but continues to have some of those deeper cultural and scientific articles and other types of things that make The New Yorker The New Yorker. One of my favorite interviews and chapters of the history of the magazine though is Tina Brown, who is just a dazzling person, character, very controversial.

When she came in, she was a 38-year-old comet, as David Remnick describes her, that just blasted into the magazine, decided to open the windows and let fresh air in. A lot of people were worried that she was going to make it celebrity obsessed and a little too zippy. She had a line that she liked to say which was that she wanted to make the sexy serious and the serious sexy. She just wanted to give that magazine a new set of energy.

Alison Stewart: Let's take a final call. Marie in Fort Greene, you're our final call. You're on the air.

Marie: Hi, thanks for taking my call. I wanted to share that when I was in my 20s in New York 20 years ago, I was an avid New Yorker reader, and I was known for making birthday issues for my friends. I would choose my favorite articles for them based on their interests. Someone who was very into engineering or Ernest Shackleton or Mary Carr poems, I would pick my favorite pieces for them and then I would use my office computer to photocopy, because this was 20 years ago.

I would make them their own issue, and I would bind it and then I would make a table of contents. I somehow found the font, and I probably made it in Microsoft Word. I would make them their own New Yorker, and it would say, for example, Robert's 25th Issue for his 25th birthday. It would list the articles and then they would have their own New Yorker custom made for them. I did that maybe four times. That's the most special memory I have of The New Yorker.

Alison Stewart: That's a great gift, by the way.

Marshall Curry: I love that. It really reflects the spirit of the magazine itself. I remember when I first got there, at one point I wrote down a word and stuck it on my computer so that it would be my North Star. That word was 'obsession'. That the people who work at The New Yorker are obsessed. They are a fact checker. They have 27 fact checkers on staff who are obsessed with fact checking. They're obsessed with writing.

They have multi-hour sessions where they go paragraph by paragraph to make sure that every word is as precise and perfect. They're obsessed with grammar, they're obsessed with deep reporting, with the way that the graphics on the covers come together. To me, that's what was so fun about making this film, was just watching this group of completely obsessed people put this magazine together every week.

Alison Stewart: The name of the documentary is The New Yorker at 100. You can stream it now on Netflix. My guest has been Marshall Curry. Thanks for coming in and thanks for taking listeners calls.

Marshall Curry: It's been a real pleasure. Thank you.