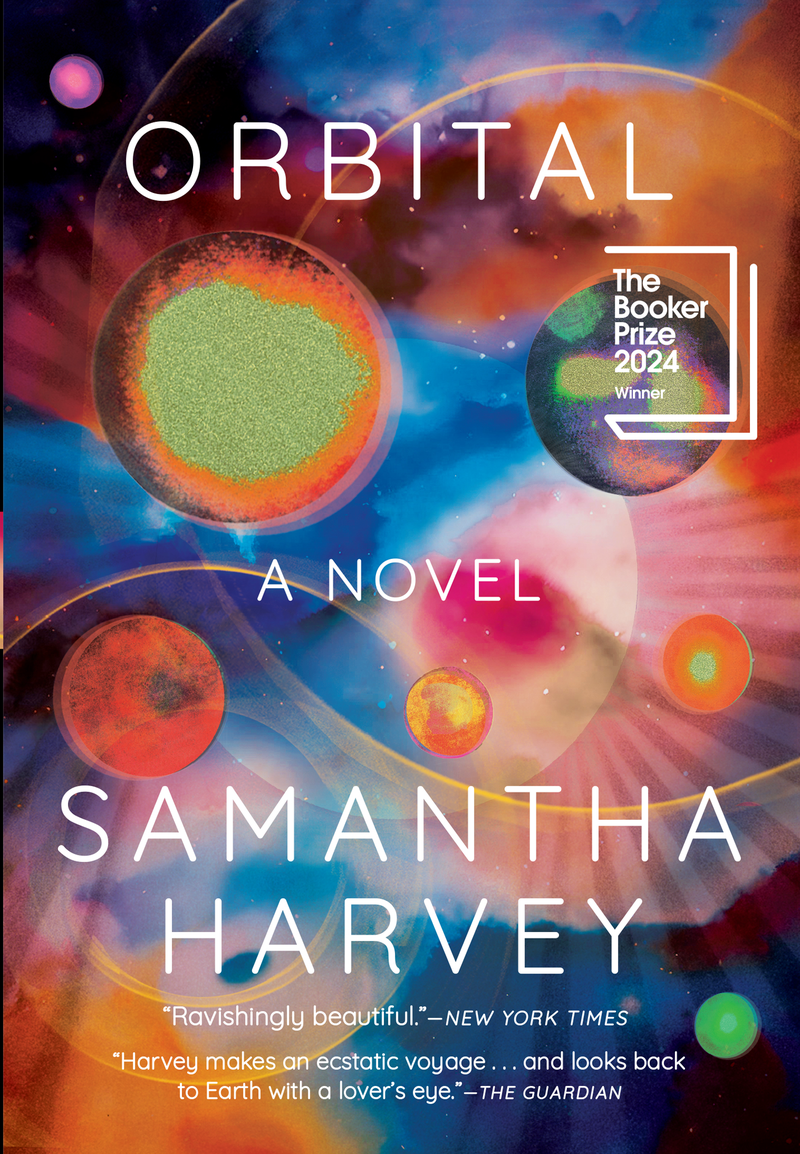

Booker Prize Winner Samantha Harvey on 'Orbital'

( Courtesy of Grove Atlantic )

[music]

Alison Stewart: You are listening to All Of It on WNYC. I'm Alison Stewart. To close out our Book Week here on All Of It, let's talk to author Samantha Harvey, who just won this year's Booker Prize for writing a space novel that's really a lot about Earth. The book is titled Orbital and it captures one day in the lives of six astronauts orbiting the Earth in the International Space Station.

Four men and two women are scheduled to spend nine months at the ISS. Each day, they experience 16 sunrises and sunsets. Their day is both extraordinary and mundane. They monitor a deadly typhoon from above and they run on a treadmill. They ponder questions about humanity, about religion, about aliens while trying to fix a broken toilet. The novel itself is meditative, beautiful, and wide-reaching even as most of the action takes place in an enclosed space station.

The Booker Prize judges wrote, "In an unforgettable year for fiction, a book about a wounded world. Sometimes you encounter a book and cannot work out how this miraculous event has happened. As judges, we were determined to find a book that moved us. A book that had the capaciousness and resonance that we are compelled to share. We wanted everything. Orbital is our book." Orbital is about now and Samantha Harvey joins me now from the UK. Hi, Samantha.

Samantha Harvey: Hi, Alison.

Alison Stewart: We're speaking to you fresh off your Booker Prize win. What did it mean for you to win for this novel in particular?

Samantha Harvey: It's completely overwhelming, unexpected. I had absolutely no notion that I would win it. I was just delighted to be on the shortlist and thought the journey would probably end there. If so, that had been a privilege and great in itself. I was utterly overwhelmed to win. I'm still overwhelmed, I must say, three weeks later.

Alison Stewart: I want to play a little bit of your acceptance speech from the Booker. Let's listen.

Samantha Harvey: I suppose it's fair to say that no Booker speech has ever been made in a perfect world, but it's hard to not acknowledge the imperfections of the world that we live in today. We are, as Carl Sagan said in his book, Cosmos, the local embodiment of a consciousness grown to self-awareness. We are star stuff, pondering the stars. I would add that we are also Earth stuff, pondering the Earth. I think my novel is an exercise in that pondering.

To look at the Earth from space is a bit like a child looking into a mirror and realizing for the first time that the person in the mirror is herself. What we do to the Earth, we do to ourselves. What we do to life on Earth, human and otherwise, we do to ourselves. "Our loyalties," Sagan says, "are to the species and to the planet. We need to speak for Earth," he says. I would like to dedicate this prize, therefore, to everybody who does speak for and not against the Earth, for and not against the dignity of other humans, other life, and all the people who speak for and call for and work for peace. This is for you. Thank you.

[applause]

Alison Stewart: Samantha, what did you want to accomplish with that speech?

Samantha Harvey: Well, I have to say, firstly, I wrote the speech absolutely believing I wouldn't have to read it out.

[laughter]

Samantha Harvey: It was a great surprise to me to find myself standing there reading it. I think that although I never intended Orbital to be a political book, I see it much more as an exercise in trying to paint with words, trying to paint a picture of the Earth with words from an interesting and extraordinary vantage point, which is a space station. It is, nevertheless, I think, by implication, a political book. It's a book that has to be about climate change because, what do we see when we look at the Earth and the impact of humans upon the Earth?

I wanted to acknowledge that in my speech. I wanted to acknowledge the things that are happening in the world at the moment. I didn't think I could just leave that unsaid. The war in Ukraine, the war in Gaza, as it was then very recent re-election of Donald Trump. There was a lot that I wanted to speak to, I suppose, but I don't want to be overtly political in my novel or really in my own personal life, my public life, I should say. I do want to acknowledge that we live in a world that is, at the moment, very full of struggle and pain, as well as great beauty. I didn't feel that that could be left unsaid.

Alison Stewart: My guest is Samantha Harvey, the author of Orbital. It just won the 2024 Booker Prize. I read in The Guardian that you almost gave up on this novel. What made you keep going?

Samantha Harvey: Well, I'm really not a quitter when it comes to writing, so I've never given up on a novel before. When I wrote a few thousand words of this one, it wasn't that I thought I should give up because it was too difficult or I had a better idea. It was more that I felt that it wasn't credible for me to write it. I'm just a woman living in southwest of England. I have never been to space. I will never go to space. I'm so utterly, constitutionally not an astronaut.

It felt that it was just too far-fetched for me to write it and that nobody would want to hear what I have to say about such things. I put it aside and I started other things and couldn't commit myself. I came back to the book that is now Orbital. That wasn't called that then. I read what I'd written. This was a few months later. It was only maybe 5,000 words or so, but it crackled with a kind of energy and the life force that I hadn't quite realized was there when I started writing it. I just knew it was the book I wanted to write and that I would have to make it good enough to justify that act of trespass, I suppose.

Alison Stewart: I'm going to ask you to read the first couple of pages of Orbital so people can hear your voice.

Samantha Harvey: Rotating about the Earth in their spacecraft they are so together, and so alone, that even their thoughts, their internal mythologies, at times convene. Sometimes they dream the same dreams, of fractals and blue spheres and familiar faces engulfed in dark, and of the bright energetic black of space that slams their senses. Raw space is a panther, feral and primal. They dream it stalking through their quarters.

They hang in their sleeping bags. A hand-span away beyond a skin of metal, the universe unfolds in simple eternities. Their sleep begins to thin and some distant earthly morning dawns and their laptops flash the first silent messages of a new day. The wide-awake, always-awake station vibrates with fans and filters. In the galley are the remnants of last night’s dinner, dirty forks secured to the table by magnets, and chopsticks wedged in a pouch on the wall.

Four blue balloons are buoyed on the circulating air, some foil bunting says, "Happy birthday." It was nobody’s birthday, but it was a celebration and it was all they had. There’s a smear of chocolate on a pair of scissors and a small felt moon on a piece of string tied to the handles of the foldable table. Outside the Earth reels away in a mass of moonglow, peeling backward as they forge towards its edgeless edge. The tufts of cloud across the Pacific brighten the nocturnal ocean to cobalt.

Now, there’s Santiago on South America’s approaching coast in a cloud-hazed burn of gold. Unseen through the closed shutters the trade winds blowing across the warm waters of the Western Pacific have worked up a storm, an engine of heat. The winds take the warmth out of the ocean where it gathers as clouds, which thicken and curdle and begin to spin in vertical stacks that have formed a typhoon.

As the typhoon moves west towards Northern Asia, their craft tracks east, eastward and down towards Patagonia, where the lurch of a far-off aurora domes the horizon in neon. The Milky Way is a smoking trail of gunpowder shot through a satin sky. Onboard the craft, it’s Tuesday morning, 4:15, the beginning of October. Out there, it’s Argentina, it’s the South Atlantic, it’s Cape Town, it’s Zimbabwe. Over its right shoulder, the planet whispers morning, a slender molten breach of light. They slip through time zones in silence.

Alison Stewart: That's Samantha Harvey reading from her book Orbital. It won the Booker Prize in 2024. What kind of images or videos did you look at to understand what Earth would look like from the International Space Station?

Samantha Harvey: Well, we're really blessed with hundreds, thousands of images and of video footage of the Earth from low Earth orbit. Primarily, from the International Space Station. Actually, it's quite an easy subject to research. There is an ISS live tracker, so you can watch the live webcam theoretically 24 hours a day from the ISS, although it often seems not to be working. [chuckles] You can follow their orbit in real time, so I did that. When that wasn't working, I just looked at pre-recorded orbit videos and photographs astronauts have taken.

You can get in an immense amount of detail of the Earth view from space by doing that. I probably watched thousands of hours of those while I was writing the book. I had video footage on my screen all the time. It's a very, very descriptive novel. It's largely about the Earth and what they can see. It's nature writing, I think, from space. I needed to keep returning to those images to be able to evoke the scenes I was seeing and to try to find ways of conjuring this extraordinary landscape that's both familiar and very unfamiliar.

Alison Stewart: There are six astronauts that you write about. What kinds of people did you know you wanted to populate your space station?

Samantha Harvey: I was somewhat bounded by reality on this in that I wanted to make the novel as close to the facts of the ISS as I could. There are always NASA astronauts on the ISS. There are always Russian cosmonauts. There are sometimes Japanese astronauts, so I have a Japanese astronaut. There are usually European astronauts from the European Space Agency. I wanted to create a spectrum of nationalities.

I wanted this to feel like a truly international novel because I think one of the things that drew me to this subject matter as well as this visual project of trying to paint with words was the sense of the ISS as an experiment in peaceful international cooperation and I would say an experiment that has been incredibly successful in its 25 years. It's part of an era that is passing.

I think that there's a sort of element of nostalgia to that that we see that those collaborations that grew out of the Cold War and the desire to make reparations between Russia and the West after the Cold War, that era is really coming to an end. We are not enjoying that peace anymore. I wanted it to be representative of what the crew of the ISS is and for it to feel international and to feel like a memorializing of this peaceful era that we have lived through, at least in the West and in this regard.

Alison Stewart: Because it's the International Space Station, you have Americans, Russians, UK, Italy, Japan. The Russians even call themselves cosmonauts instead of astronauts. How do these astronauts bring their national identities with them to space?

Samantha Harvey: I guess it's a funny thing. I think in one sense, your nationality ceases to matter, I imagine, when you're up there because you're just six humans and you've got to get on with one another. You are everything to one another. They cut one another's hair. They have to do each other's dentistry. [chuckles] They have to confide in one another. They have to be each other's support systems.

In a sense, those national boundaries cease to have very much relevance. In another way, they are the sole representatives of their nation while they're there. The only analogy I have for this myself is having lived in Japan for a few years. I think that while I lived in Japan, I've never felt more British. [chuckles] There was something about being away from home that makes you feel your own national identity more acutely.

I guess, and I am guessing because, obviously, I am not an astronaut. I guess there's both a sense of the melting away of national identity, but also the strengthening of it. Because if you are the sole Italian astronaut on the space station, then you represent all of Italy for that time. I found that very interesting that that heightened and weakened at one sense of the relevance of national identity.

Alison Stewart: Because everything takes place within these walls, within the space stations enclosed, there's only so much that can happen. What challenges did that present to you as a writer to write about these people confined into the space?

Samantha Harvey: Well, I very much love writing novels in which not very much happens. [laughs] I love reading them too for that matter. It's not that I have any disdain for plot. I really don't, but I wanted this novel to be one day on a space station. On any given day on the ISS, no real plot happens, thankfully. No astronaut wants there to be much plot while they're up there. I wanted it to be just a day of domesticity, I suppose.

I'm really interested in this idea of space as a domestic lived environment. We don't really think about it as such. We think about it in terms of sci-fi and usually catastrophizing what happens to humans in space. In fact, it's a lived environment, so I wanted to explore that. I wanted also to explore the idea of fiction that doesn't rely upon conflict to generate its drama and its propulsion.

I'm really interested in that as a writer. I want to know what things narratives have at their disposal to keep people reading and to keep it breathless and to keep the dream state and the spell of the novel going without there having to be plot as such. Conflict and drama. I think this novel is an experiment in that in some sense because I feel like that's true to the premise of the book.

It's just one day going around and around the Earth. It's, in a sense, intensely repetitive and, as you said in your introduction, intensely mundane. They spend a lot of time vacuuming and dusting. Yet, of course, it's utterly extraordinary. I love the coming together of those disparate things, those almost paradoxical things. That's what I wanted to try to evoke in the prose and to create a sense of propulsion through all of those bizarre contradictions and paradoxes.

Alison Stewart: There are so many lists in the book. Lots and lots of lists of things.

[laughter]

Alison Stewart: Why were there so many lists?

Samantha Harvey: I guess I just like a list.

[laughter]

Samantha Harvey: In a way, I wanted the writing to have a breathless and in repetitive quality in itself at times, a musical sense of repetition of things. Actually, there were more lists in it than I realized. I had to remove a few [laughs] in some of the edits. I wanted to capture something about the way life on the space station, as I understand it, is also extremely regimented. They do live by lists and schedules and trying to rationalize and make logical everything. I think there's some of that in the writing as well, so trying to evoke some sense of orderliness or trying to contain in list form, the crazy expansion and extraordinariness of their experience.

Alison Stewart: I couldn't help but notice the astronauts are supposed to be up in space for nine months, about the same time as pregnancy.

Samantha Harvey: [laughs]

Alison Stewart: How did you land on nine months?

Samantha Harvey: That wasn't an intentional metaphor. I think the missions to the space station do tend to be somewhere between six and nine months. I want it to be at the slightly longer end. They're not all there. They don't all arrive at the same time, so their missions overlap. They don't all stay for the same nine months. I wanted to base that on fact. I think the missions are usually more like six, but I decided to expand theirs a little bit.

Alison Stewart: The astronauts have to cope with their physical health and their mental health, but truly their physical health. How do the astronauts cope with this risk, the risk on their bodies, the risk in their minds?

Samantha Harvey: As far as I know from the research I did, I think being in space for that long, being in microgravity, because it's the microgravity that is the complicating factor. It has all sorts of strange effects on the body, which I think tend not to last beyond re-entry to the Earth. A lot of the damage that's done is reversible, but all sorts of things happen at a cellular level. Things happen to their organs, their eyes.

I think the eyes [chuckles] move around more in the socket because there's no gravity to keep your blood moving around your body, so it all tends to move towards your head. You get blocked sinuses. The eyes move around in the fluid more. Sleep is obviously difficult because you are experiencing 16 days and 16 nights in a 24-hour period. You're going around the Earth in 90 minutes. Your circadian rhythms are completely shot. I think there's a lot that is done to try to compensate for those things.

The vast amounts of exercise they have to do to prevent muscle atrophy because the body isn't working against gravity all the time. One thing I found fascinating when I was researching this was to see that they are not only scientists who are doing science on the ISS, but they are also lab rats. A lot of science is being done to them. They are being continually monitored. They are part of the experimentation that's happening up there, partly to see how humans can endure long-

Alison Stewart: -trips in the space.

Samantha Harvey: Long trips in space. Exactly.

Alison Stewart: The name of the book is Orbital. It just won the 2024 Booker Prize. My guest has been Samantha Harvey. Thank you for spending time with us, Samantha.

Samantha Harvey: It's my pleasure. Thank you.

Alison Stewart: That is All Of It. I'm Alison Stewart. I appreciate you listening and I appreciate you. I will meet you back here next time.

[music]