Asian Heritage Chefs Who Cooked for U.S. Presidents

Alison Stewart: This is All Of It on WNYC. I'm Alison Stewart. Coming up in about a half an hour, poet and author Ocean Vuong. His new novel is titled The Emperor of Gladness. It's about a young man in a small Connecticut town who becomes a caregiver for an elderly woman with dementia. The Los Angeles Times calls it, "magnificent and melancholy." Ocean Vuong will be here in studio to discuss.

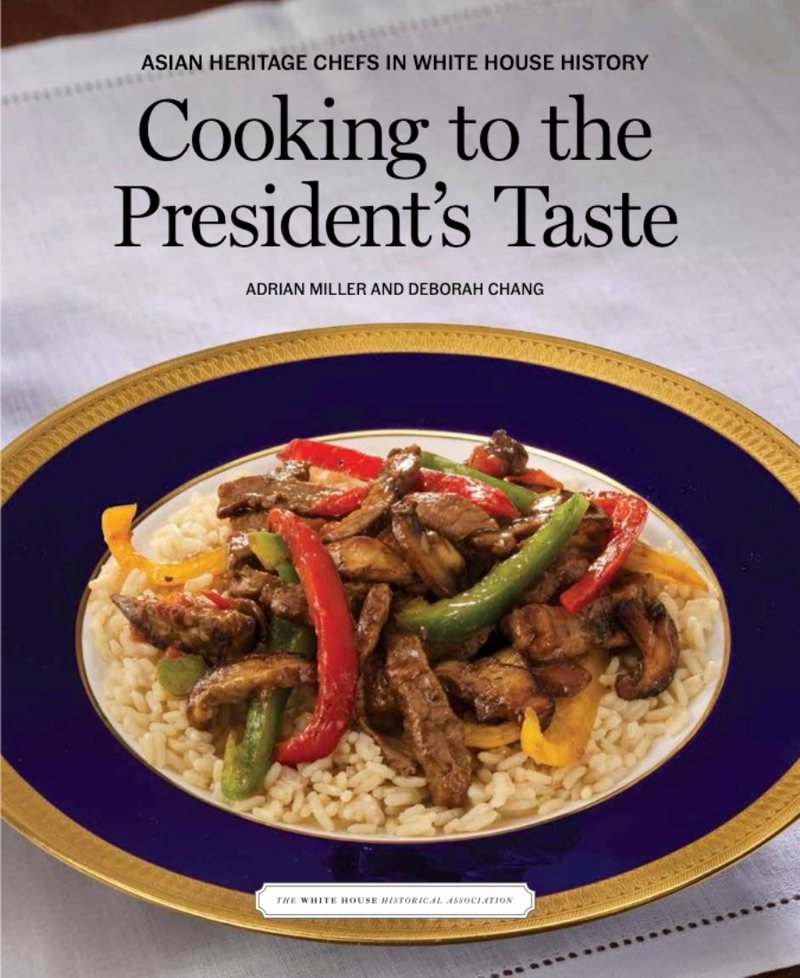

Now, let's get this hour started with Asian Heritage Chefs in White House History. In honor of Asian American and Pacific Islander Heritage Month, a brand new book spotlights Asian heritage chefs who have prepared meals for Presidents at the White House, at state dinners on Presidential yachts. Some of the names include Chinese American chefs like Lee Ping Quan, Anita Lo, Chef Ariel de Guzman from the Philippines, and Korean American chef Edward Lee. Alongside these in-depth interviews and the accounts of these chefs preparing meals on these special trips and with peace negotiations, there are recipes.

Who knew that President Coolidge had a favorite curry and rice dish? Asian Heritage Chefs in the White House History: Cooking to the President's Taste is out now. Adrian Miller is known for his books on African American culinary history. Adrian, welcome to All Of It.

Adrian Miller: Good to be with you.

Alison Stewart: Deborah Chang is a writer and a cook. Deborah, welcome as well.

Deborah Chang: Thank you.

Alison Stewart: I want to read this quote about the book. It's from the introduction and this question is for both of you. It says, "This book demonstrates that White House culinary history is not just about food." Adrian, what's the book about?

Adrian: This is a unique window on the American presidency told from the perspective of Asian heritage cooks. We've never had that before. There have been newspaper articles here and there, but it's never been put in one place. I think it provides a unique window on the American presidency that goes back more than a century, which is something I didn't even know until I started the journey on this book.

Alison Stewart: How about for you, Deborah? What is the book about?

Deborah Chang: Asian American contributions to U.S. history in a way that many people today likely didn't know about.

Alison Stewart: Adrian, you had to do research for this book. Where did you start?

Adrian Miller: I started in the University of Denver. My hometown has a special collections with a cookbook collection of thousands of volumes. I was working on a book previously about African American Presidential chefs. I just put in Presidential cooking, Presidential chef into the search engine for the catalog, and up popped this cookbook written by Lee Ping Quan, who was a Chinese immigrant. He wrote that book in 1939 and published that. Previously, we had not had really in-depth memoirs of people who had cooked for our President. It's part memoir, part cookbook.

I said, okay, I'm working on Black chefs, but I'm gonna just hold onto this and then come back to it, and I did revisit it. It was really looking at that book, also historical newspapers and then Presidential memoirs. Then I had to go to the National Archives and just dig into the records of the Presidential yacht. The captains had to list everybody who served on the ship, their positions and where they were from, and that was a goldmine.

Alison Stewart: Oh, I imagine. Deborah, how did you collaborate on the book with Adrian?

Deborah Chang: I was brought into the project because-- Adrian and I know each other from college, and we've known each other for a very long time. It came to fruition because he needed someone to bring these recipes to life. I've had many versions of my career, one of which was I went to culinary school and was a professional chef for a while, and so it was the crossing of many things and the right time. That's how I got involved in the book.

Alison Stewart: Adrian, you came across Lee Ping Quan

's memoir. What struck you about his story and then what struck you about his career?

Adrian Miller: One thing that struck me about his story is that this memoir was pretty good about talking about his early life. This guy was trained as a chef at a very young age. He arrives at to the U.S. Navy already having a lot of game when it came to cooking. I was really impressed by his skill level, coming to that, and then his willingness to talk about his experiences cooking for Presidents, what they loved. He was willing to dish on Presidents, and that's what people are curious about, that kind of stuff.

The skill level that he brought, his ambition, even after serving with the Presidents, he opened up restaurants in New York City and in Maine and other places, leveraging his fame as a Presidential cook. I just like this guy's moxie.

Alison Stewart: All right, tell me some of the dish.

Adrian Miller: We talked about the favorite dishes of President and First Lady Coolidge, Calvin Coolidge and Grace Coolidge. They loved the curry dishes, but she really loved his chop suey, and he actually taught her how to make the chop suey. Then one other funny story is Herbert Hoover wasn't feeling having a Presidential yacht, so he was going to decommission the U.S.S Mayflower, which is the yacht that Lee Ping Quan

was on. It was time for Hoover's birthday, and Quang was known for making these cakes, but he was mad at Hoover for decommissioning the Mayflower. When a journalist asked him about the cake he was gonna make for the President for his birthday, he just said, "No Mayflower, no cake." As I write in the book, his flavor profile towards President Hoover was salty.

Alison Stewart: Deborah, A lot of Lee Ping Quan's recipes are featured in the book. What's notable about them? What's notable about the way he cooked?

Deborah Chang: Many things. The first was, I was struck by the order of the recipes in the original cookbook, which he put the Chinese recipes first. He didn't put state dinner recipes or fancy entrees first, or appetizers first, like we see today. He put Chinese, and I thought that was really interesting and a big hook for me to get involved. That was a big surprise to me, that this was a hundred years ago.

Then with the rest of his recipes, his scope of ability and talent was amazing. Not only was he very skilled at Chinese cooking, he could do everything. Particularly, he could produce big state dinners with really elegant meats of the time, like filet mignon and fancy meats. Meats for the time, like lamb, I imagine, but he also had to cook for the kids. He had to cook breakfast, all the scope of those kinds of recipes. Then he seemed to have a really talented pastry ability as well. This is what Adrian talked about, a lot of cookies, a lot of dessert, a lot of cakes were included in the original book as well.

Alison Stewart: Adrian, what does one need to do to become a chef at the White House? What Deborah just listed was huge, a huge amount of responsibility.

Adrian Miller: Yes. For a lot of these Asian heritage chefs, the military was the primary route towards Presidential cooking. They often enlisted in the Navy because they viewed it as a path to U.S. citizenship. As they rose in the ranks in the Navy, then ultimately they were referred to to serve on the Presidential yacht, which we no longer have because President Carter sold it off in the 1970s. That's one route.

Also, typically in the 19th century, people just happen to be the family cook of the person who became President, so it was someone who already knew the President. These days, a lot of it is based on your professional reputation and also who you know. When the White House chef opening is announced, it is a Civil service position, so there is a formal announcement, but people get recruited, recommended, and then you have to try out by basically cooking all kinds of food to make sure that you can please the first family.

Alison Stewart: We are talking about Asian heritage chefs in White House history: Cooking to the President's Taste. It's a new book that spotlights Asian heritage chefs in White House history. Co authors Adrian Miller and Deborah Chang join us to discuss. Deborah, you had the task of selecting recipes that can be made in a modern kitchen. How did these chefs introduce dishes to the President that weren't necessarily popular within their respective cultures?

Deborah Chang: I'm sorry, can you repeat the question?

Alison Stewart: How did these chefs introduce dishes to a President that has maybe never heard of it before? They've never heard of a certain dish before?

Deborah Chang: I think that spoke a lot. I mean, it spoke a lot to the trust that the Presidents had in the people that cooked for them. Maybe not so much today in modern times, I mean, we have recipes from contemporary chefs, and I think Asian cooking and Asian ingredients are pretty prevalent in America today. Particularly Chef Quan

It was eye-opening that President Harding, President Coolidge, they were open to tasting, to eating chicken chow mein and having ingredients like water chestnuts and bamboo shoots. I don't know if that was my implicit assumption that they wouldn't be open minded, but it was really cool to see that they were open minded to different.

I've always thought food was a connector, and you hear that a lot in food discussions, but this is where you really see two different cultures coming together and a way of learning about a certain culture through food. It's always interesting to see that being brought to life.

Alison Stewart: Deborah, in the book, there's a recipe for chicken chow mein, which is listed as one of Mrs. Coolidge's favorite meals. What's interesting about the original recipe?

Deborah Chang: Besides the fact that it existed 100 years ago, which I thought was interesting, and it exists in a version today, I thought was like, "Oh, well, Chef Quan must have been like an early influencer, an early influencer of Chinese food." I thought that was pretty fun to think about. Then the original recipe with his--

One of the overarching issues that I had with translating the historical recipes to modern times, was how many changes should I make, because I wanted to be historically accurate, yet it has to fit with modern tastes and be able to cook in a modern kitchen by a regular person. With that particular recipe, how I adapted it was we have different sets of vegetables and available today. I made suggestions as to different kinds of vegetables that we could use. I suggested fresh bamboo shoots, fresh water chestnuts, instead of the canned that we have today.

That was likely what Chef Quan was using. He wasn't using canned, whatever brand in the supermarket aisle, he had fresh.

I had to make judgments a lot. I think that recipe had-- there is just stuff I just don't know what he meant. Leeke, he said, I think he said beans, like 1 pound Chinese beans. It could be green beans, it could be bean sprouts, it could be fava beans, and so I think if he meant bean sprouts, he would have said bean sprouts. I think if he said green beans, he would have said green beans, but honestly, I don't know. If he were alive, that is the question that I would ask him, is what he meant.

The general concept of noodles, plus stir fry, plus sauce, that concept was there, and it's just a matter of altering the vegetable, altering the noodle, and altering the sauce. To the extent that I could explain it, I did.

Alison Stewart: Adrian, what did you learn about how U.S. foreign policy played out in these Presidential kitchens and with these menus?

Adrian Miller: It's really interesting. We have a number of examples of where these chefs were tasked with hospitality for dignitaries. One interesting story, I'm not going to give it away, because I want people to read the book, is there was a guy named Irineo Esperancilla who was a Presidential yacht steward for Hoover, Roosevelt, Truman, and Eisenhower. He was actually serving a meal where President Roosevelt was meeting with Joseph Stalin. Stalin, not familiar with Filipinos, thought he was Japanese. Esperancilla definitely showed grace under pressure coming up with that meal.

Now contemporary menus, and we include two state dinners in our book, you want to give a flavor profile to the visiting dignitary, but also celebrate American ingredients. It's a delicate collaboration between the State Department, the White House cooks, the Presidential chef, and also the first family. Just figuring out how to put America's best foot forward, but also make that dignitary feel welcome. Just navigating dislikes, tastes, food considerations, taboos, all of that stuff is pretty fascinating.

Alison Stewart: Deborah, what do you hope people take away from the book?

Deborah Chang: I really like being involved in projects where Asian Americans contributions are brought to the forefront and where Asians are in an important leadership role. This is one way that I had never thought about. Today, executive chefs are elevated in status. They write books, they're in the media a lot, and I like how we're bringing Asian American chefs and their leadership and contributions to the forefront.

Then I think cooking the recipes and including the recipes allows people to have a connection to history in a different way, instead of just flipping through an old book and saying, "Oh, that's interesting. This recipe looks interesting," to actually cook it. I've learned a lot about each chef through the cooking, even the contemporary chefs, particularly the Filipino recipes.

We have recipe for pancit in the cookbook. Learn something new and have a connection to White House history, American history, that I wouldn't have had if not for this book.

Alison Stewart: Adrian, what did you learn working on this book?

Adrian Miller: I learned that this book is really an appetizer for further exploration of Asian American contributions to the American Presidency, because I just did not know that this legacy in terms of the culinary went back so far and how that people of Asian heritage were actually preferred by U.S. Navy personnel after the Spanish American War, ultimately displacing the African Americans who had dominated these positions on ships. Just to see that transition, and then also to see how these racist attitudes that were often visited upon African Americans got transferred to Asian Americans and thinking of them as a servile race and born cooks and all of that kind of stuff.

To see that play out was really, really fascinating. But I think the positive is that this is a window on the American Presidency that went both ways. I think our first families learned a little bit about what it was like to be an Asian American in our country. Those that delved a little deeper, I think our country is better for it.

Alison Stewart: I've been speaking with Adrian Miller and Deborah Chang, the co authors of the new book titled Asian Heritage Chefs in the White House History: Cooking to the President's Taste. It is out now. Thanks for your time today.

Adrian Miller: Thank you.

Deborah Chang: Thank you.