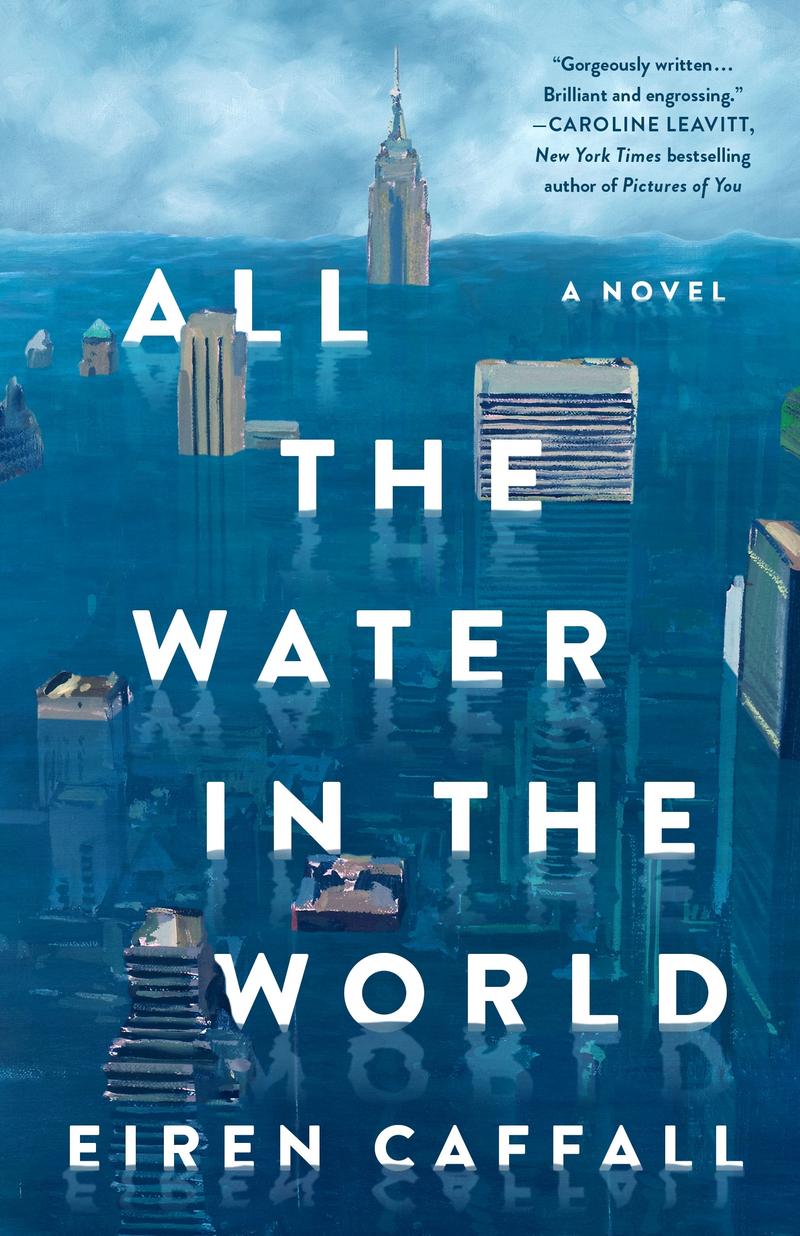

'All the Water in the World' Follows a Settlement on the Roof of the AMNH

( Courtesy of St. Martin's Press )

Alison Stewart: You're listening to All Of It on WNYC. I'm Alison Stewart. In the new novel, All the Water in the World, Lower Manhattan is underwater. Much of the city is unlivable thanks to climate change. Luckily for a girl named Nonie, she and her family have found a safe place – the roof of the American Museum of Natural History. Nonie's mother used to work there before everything collapsed. Now a group of former employees and their loved ones have formed a settlement they call Amen.

That community is dedicated to the survival of the museum. They spend their days cataloging the treasures of the collections. When a massive hurricane hits a hypercane, the museum finally floods. Nonie and her family flee in a canoe they've taken from the museum's collection and head into the unknown with the logbook in tow.

All the Water in the World is the debut from writer Eiren Caffall. She was inspired by the real-life stories of museum curators going to great lengths to protect their collections in the midst of World War II and the 2003 invasion of Iraq. Eiren is also a science journalist and a nature writer who draws on her years of experience for this novel. She joins me now. Hi, Eiren.

Eiren Caffall: Hi, Alison.

Alison Stewart: You're a science journalist and a nature writer. What do you think fiction can convey about the climate crisis that nonfiction can't?

Eiren Caffall: I think that fiction can take us to places where we can access the facts and the information that's available to anyone in the science, but give us an imaginational window into it so that we can practice what we feel in a safe world that can maybe be a little bit less real and terrifying than the day-to-day statistics that we're reading. At least that's how it worked out for me as a writer working in a different genre.

Alison Stewart: It's your first novel.

Eiren Caffall: Yes.

Alison Stewart: How is your background as a science writer helpful to you?

Eiren Caffall: Oh my goodness, incredibly helpful. I was raised by scientists. I spent many years, and still do, working as a science journalist doing a lot of research and having a lot of conversations with activists and scientists, and doing just huge deep dives into papers about ocean acidification, global warming, climate collapse, and ecosystemic change. During the writing of this book, which took me 11 years, I was going back and forth between the memoir I was working on, which was very much based in the present, and also this imagination of what would happen if the worst-case scenarios that I was reading about came to pass.

My first draft of the book actually was twice as long as the book that you can get now because I was so [crosstalk].

Alison Stewart: I'm sure you had all that research, right?

Eiren Caffall: Right. It was huge. I was just deep with all this research because I really wanted to make sure that-- My mom and I used to, for fun, watch all of the movies where the scientists are the heroes, and so I really wanted to make sure that what happened to us whenever somebody got the geology wrong and my mom [laughs] couldn't concentrate on the movie would not happen to somebody reading the book. That if a scientist picked it up or a curator or somebody who wanted to go to the museum or somebody who grew up in New Jersey picked it up, they would be able to recognize a world that felt real, even if I was positing a future that is pretty horrific.

Alison Stewart: I know you did some research into what museum curators in Stalingrad and in Iraq did to help save their collections. What did you learn about the work they did, and how did that help you with this novel?

Eiren Caffall: I knew about it a little bit in the periphery from reading that I'd done before I started the research on the book, but I read Anna Reid's fantastic book Leningrad, and of course, I read Monuments Men. One of the things that I found to be so fantastic was that this idea that I had that people would stay because they felt a duty to the collections that they had been part of curating was absolutely true. In Leningrad, the curators stayed for the entirety of the siege, the full three years of starvation. They made a makeshift community in the basement of the hermitage, and they chipped the ice off of the masterpieces. They ate restorer's paste and they slept on palace furniture and buried their dead.

They did that because the people who had chosen to stay behind didn't just feel that it was a job, it was a calling, and that they were protecting something for a future that they were trying to imagine on the other side of the siege. That every story I read about that kind of dedication to scientific knowledge, to curation, to preservation of the past, to being an archivist or a librarian, every time I read a story it reminded me that the work that even someone like my mom was doing to preserve information and scientific knowledge was part of the same drive of this isn't just about that I like to go to work in the museum. This is my duty. This is my calling.

Alison Stewart: And more, they say destroy the culture first.

Eiren Caffall: Yes, exactly. We've seen that over and over again. There's ongoing work in the Ukraine right now to try to restore sites that have been bombed. Obviously, we've seen incredible devastation in Gaza. It's part of sustained attacks on information. Also the future of science. I think it's significant that preserved bird skins from 18th century, 19th century trips to collect information about bird populations worldwide were moved from London into the country during the blitz because there's this sense of if you can hold on to that information-- I'm so sorry, my cat has decided to go hunting.

Alison Stewart: That's okay.

Eiren Caffall: If you can preserve this information, that you also are preserving the possibility of restoring the culture that the conflict is trying to destroy. I think of that even-- Right now I've been following a lot of the scientists who are downloading and preserving scientific data from federal websites as they go dark because they are trying to make sure that that's there for future generations, for future scientists, future years.

Alison Stewart: Did your cat bring you a present?

Eiren Caffall: She did. She loves to hunt. It's probably a stuffed lamb. [laughs] It's not real. We have [unintelligible 00:06:31].

[laughter]

Alison Stewart: Okay. I'm speaking to Eiren Caffall, author of the new novel All the Water in the World. It's about a group's attempt to save the American Museum of Natural History amidst a climate disaster. I'm going to ask you to read a little bit from the book. This passage tells us how things in the city begin to deteriorate just before the flood sent the family to the museum. Could you read those two pages for us?

Eiren Caffall: Yes, absolutely. This is Chapter 7: The world as it was. "Storms always came. They took things. They took things before I was born. Mother and Father told me that. Bits of the coastline, glaciers, reefs, whole islands, cities. San Juan, Miami, the Azores, Shenzhen, Mumbai, the Philippines, Bangkok, Abidjan, Nagoya, New Zealand. They took water from the inland and gave it to the sea. Crops failed. Forests caught fire. Tall mountain ranges burned with the trees along their ridgelines.

People moved to places where the food was. Countries filled and emptied until the people themselves were the floods and the droughts. Mother and Father watched it happen on their laptops, reading articles, looking at pictures of loss side by side on the couch on 10th Street, the electric off and on. Mother told me it was slow at first, the way the world changed. You could forget about it. People talked like you could fix it. A storm would pass and they'd put things back together, or one day there was no gas, and you learned to live without your car.

You learned to live without bananas, without airplanes. That's how Mother said it. She said it like losing taught you lessons you needed until you were happy to have a day with fresh water in your apartment and a bath. It was slow enough you might have babies like Mother and Father, them wondering if that was smart. Bix first, born in a hospital with power and lights before martial law. Me three years later, born at home in the dark. Things fell in slow motion. Rolling blackouts. Waves of refugees heading north and west. Army everywhere. Gas rationed, food scarce. The president in a huge ship offshore.

In the old city, they built floodgates that kept the sea outside. Blocked the ocean getting up the river. Made the city an island. We lived inside. A bowl that flooded up from the sewers when the storms came. In the old city, weather was a gamble. It was hot nearly all year, dry when you needed water, flooding so it couldn't be managed. Cold snaps would come and plunge you into ice, then melt and flood again. All the time, everyone hoping it might turn around until they knew it wouldn't. Until the world warmed up so fast you couldn't catch your breath.

Every year the storms were bigger, moving the ocean up into the streets. But there was electric sometimes. There were people in the city. None of us ever imagined Amen. There were jobs and grocery stores. We had a ration card. We drove places, and you could just take a car out on the road like that. Like it was nothing."

Alison Stewart: That's Eiren Caffall reading from her new book All the Water in the World. The family finds refuge at the American Museum of Natural History. Why did you pick that particular museum?

Eiren Caffall: Oh, because I was obsessed with it as a child. [chuckles] Completely obsessed. I was born in New York City, but my parents went "back to the land" although both of them were from the city. My mom was from the Upper West Side and my dad was from Jersey City, so they really didn't have an experience of being on the land. I grew up in this very rural place with family in the city, and so we went back a couple of times a year to visit. It was just the biggest, most important palace in my life as a child. Like many people, I was obsessed with the idea of what would happen if I could be here after everyone else was gone.

Then as a young mother, while I was writing this book while I was a single parent and I had a really little kid, we lived a bus ride away from the Field Museum of Natural History here in Chicago. We were there a couple of times a week until kindergarten started. We knew the place inside and out in the way that I had when I was younger and was obsessed with the museum.

I think for me, especially as the daughter of a scientist, as the granddaughter of a scientist, as a person who's always been interested in writing about nature even though I was an English major through and through from the first, the idea of these places as palaces to understanding, as evolving collections, as the home of really deep science research, really, it matters to me. It's a place that even yet when I go to the Field Museum member night and get to go behind the scenes, we call it Nerd Christmas. It's my favorite thing in the world to be able to go and see how people work.

I couldn't avoid writing about it if I wanted to, because when I think about what happens to my home in the worst-case scenario, I think about all the people, but I also think about what happens to these incredible institutions that represent so much of what the riches of our culture are.

Alison Stewart: The settlement at the museum, they call themselves Amen.

Eiren Caffall: Yes.

Alison Stewart: How did you arrive on that name?

Eiren Caffall: It just came to me when I started writing this character. She sort of showed up, which I always find to be a really pretentious thing that writers say.

Alison Stewart: They all say it. crosstalk]. characters just show up.

Eiren Caffall: They do. I had gotten off the phone with my godfather, who lives in Crown Heights, and he was just coming back from trying to pump seawater out of his daughter's house in Red Hook after Super Storm Sandy. He was telling me these really specific details about the way that the water had combined with sewage and oil and created this glass-like surface on the sidewalks and he nearly fell. I was really not able to sleep because the other thing that my mother would do would be to send me articles about how everything was falling apart.

I have this tiny child. I'm a single parent. I have an incurable genetic disease. I'm thinking, "God, we're so vulnerable." I couldn't sleep, and she showed up. When she showed up, she showed up with the full-- like, this is where we live. This is what we call it. It made sense to me because obviously, we call it AMNH or-- People shorten their workplaces all the time. I thought if you lived there for long enough it would slur into something.

Part of what I wanted to investigate is what do we hold onto in terms of our feeling about the future, and that really is a question, in some ways of faith. Not necessarily of Christianity, but of what kind of anchor points do we find for the future when we think about it? How do we form those communities of practice around that?

My father was also a cabinet maker for my entire life, and he made Shaker furniture. He was completely obsessed with utopian communities. I grew up with a huge library about them and going to them every weekend. I took my first steps in a Shaker museum in Western Massachusetts. That idea of how do we form communities in the face of things that feel overwhelming? What do we do? He always famously said utopias fail, so I certainly wasn't trying to find a version of this that was permanent.

I wanted to talk about how we cling to each other and create spaces for each other that are safe when things are overwhelming, and what happens when we have to evolve them and change.

Alison Stewart: Well, about 70 pages into the book, this hypercane hits and Manhattan is flooded.

Eiren Caffall: Yes.

Alison Stewart: What decision did you make about what it would look like if Manhattan flooded?

Eiren Caffall: This is a very nerdy answer, but I had a great website that I was using throughout the writing of the book, where you could flood the entire planet to whatever degree of sea level rise you wanted to play with. It sounds really morbid, but as a science writer, I loved it. I had that tab open on my computer alongside maps of New York. I had a great canoeing map of the entire Hudson that I had laid out on my desk while I was writing. Whenever I would go to put my characters in a part of the world that had been overwhelmed by sea level rise, I would compare and contrast both of those resources to try and create a picture of, well, how much of the trees would be standing up?

When they have to go past the George Washington Bridge, are they going to have to go under? Are they going to have to portage? Is it going to be underwater? Will they have to duck? My godfather, the same one I mentioned before, is a city planning professor, now retired, at St. John's. I would call him up and say, "Okay. How exactly high is the undercarriage of the George Washington Bridge? Can you help me figure it out?"

It was very detailed, and then it was this imaginative investigation into-- I write about water all the time. It's very much a muse of all of the creative work that I've done up to this point. Trying to picture what it would look like looking down into a space. Then I also read some really great writers on what happens in huge floods. There's a fantastic book called Isaac's Storm by Erik Larson, who wrote Devil in the White City about the Galveston Hurricane of 1900. I think he's just brilliant in terms of evoking what it looks like when a low-lying city is overwhelmed by an incredible tidal surge. It was a blend of all of those things.

Alison Stewart: This family sets out in a canoe after Manhattan is flooded. Do they feel hope for the future?

Eiren Caffall: Yes. I think they do, but I think they feel hope for the future because they feel hope in each other, and also because they have this discipline of imagining a world to come that they may never see. That that's part of the discipline of the work that they do in the museum. Part of their calling is we may not get to it. We may not know what it looks like. Maybe not all of us will make it there, but we are going to behave in such a way that we reinforce the possibilities of what will come.

When I'm asked about this often, what I think about is the fact that I do have an incurable genetic disease. I'm 150 years deep into that story in my family. I can't separate that sense of the baton passing of generation-to-generation hope for what might come from my own story. It was very much how I was raised. You never know what thing will arrive to change the trajectory or the fate of your own life. If you begin to believe that it's all settled and set and over and that there's no hope, you make your decisions so differently.

Alison Stewart: You have to believe in hope. The name of the book is All the Water in the World. It is by Eiren Caffall. Eiren, thank you so much for being with us.

Eiren Caffall: Thank you so much for having me. It was a total joy.