Acclaimed Pastry Chef Clarice Lam's Debut Cookbook 'Breaking Bao'

[music]

Alison Stewart: This is All Of It on WNYC. I'm Alison Stewart. Coming up on tomorrow's show, actor and comedian Jeff Hiller. You may know him as the star of the wonderful HBO series Somebody Somewhere, I was upstairs prepping the interview and watching videos, and I couldn't stop laughing, this will be a lot of fun. The Peabody Award-winning show is about to kick off its final season this weekend. He joins us to discuss.

Also, dancer and choreographer for Bill T. Jones. 30 years ago, he premiered Still/Here, his multimedia piece that told the story of people grappling with terminal illness. Now that performance is being recreated at BAM. Jones joins us along with dancer Arthur Aviles to discuss. That is coming up tomorrow.

Now let's get this hour started with a food-for-thought conversation about connecting cultures.

[music]

Clarice Lam was born in Toronto and grew up between Los Angeles and Hong Kong, two places where as a kid, she never felt like she fully belonged. Her parents would travel often, and just as often they'd return with suitcases full of candy and snacks from wherever they just visited. Food became an anchor for Clarice, especially as she traveled around the world in her 20s, trying new foods and discovering the connections between them.

She put this curiosity about food into her career when she became a pastry chef, later opening the bakery The Baking Bean in Brooklyn, and more recently working as the pastry chef at Kimika, an Italian-Japanese restaurant in Nolita.

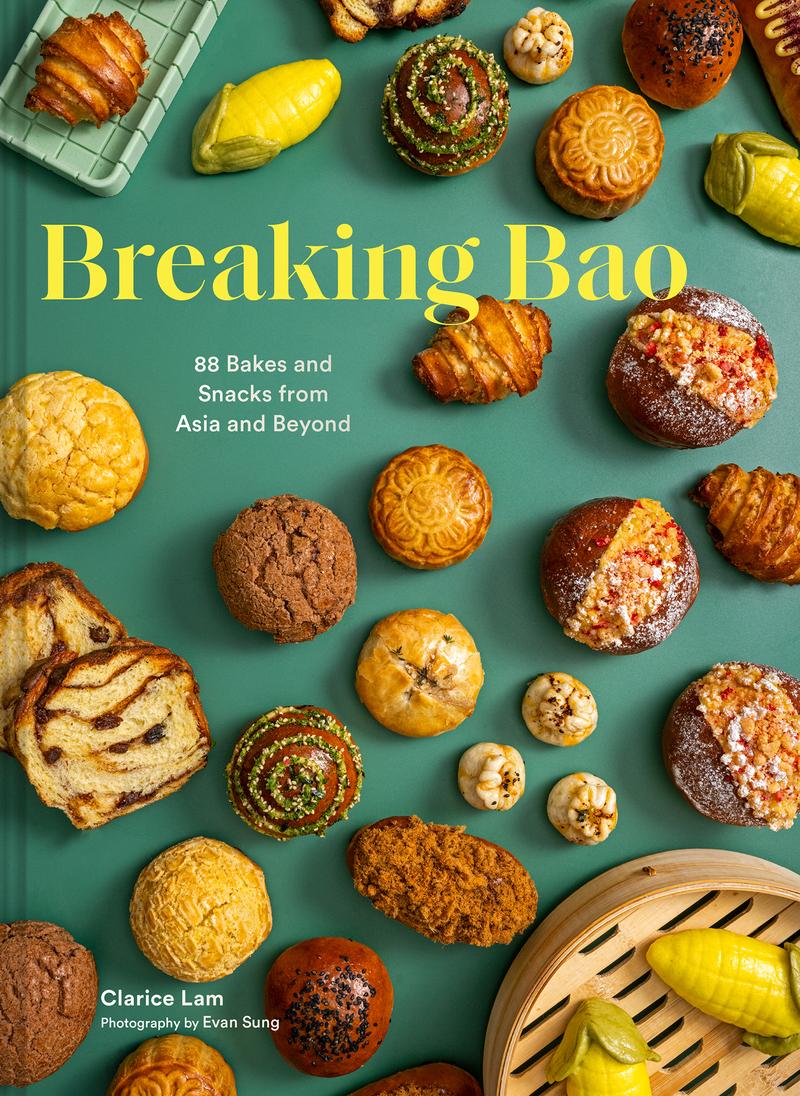

Her new cookbook is titled Breaking Bao: 88 Bakes and Snacks from Asia and Beyond. Lam combines different cuisines from her travels and career, Asian flavors made with European baking techniques, and more. Clarice Lam's book tour passes through New York this week, with events in Manhattan tomorrow and Saturday, and in Brooklyn on Sunday. Clarice, welcome.

Clarice Lam: Hi. Thanks for having me.

Alison Stewart: You write in your introduction to the book about growing up between LA and Hong Kong. You say, "While these moves were tough on me emotionally, the silver lining was always the food." What do you first remember about appreciating food as an anchor in your life?

Clarice Lam: My parents always, always told me-- like, I mean, my dad's catchphrase is literally, "You gotta eat." I was just constantly told, "You gotta eat, you gotta eat, you gotta eat." We traveled a lot, fortunately, as a family as well. They always made sure to have me try new things from different cultures, from all of the places that we've been. I always really sought comfort in all the things that we ate because they were just such special memories to me. It felt like family time, and it kind of felt like one of the only places that I truly felt at home.

Alison Stewart: Were your parents cooks?

Clarice Lam: No, they were not. In fact, my mom is a terrible cook.

[laughter]

Alison Stewart: They would just bring you suitcases full of stuff to try?

Clarice Lam: Yes. Yes, they would.

Alison Stewart: Oh, that is so funny. You write about not really fitting in anywhere you went. As a kid in LA, at an international school in Hong Kong, when you traveled the world. How did that feeling of not belonging leave you to feel maybe even less connected to your heritage?

Clarice Lam: It was very difficult. I was born in Toronto, Canada, and I grew up in LA. I think I grew up in a time-- I think times are different now, but back then, everything was really centered around, like, "Oh, what Asian are you? Can you even speak English?" Then if I'm speaking English, it's like, "Oh, wow, your English is so good." Everything just revolved around me being Asian. That kind of just became my whole identity and my only identity. I was either too Asian or not Asian enough to get modeling gigs.

Everything was like, "Oh, you're Asian, and you can't do these things because you're Asian," or, "You can do these things because you're Asian." At some point, it made me feel like being Asian was wrong. It was like, "Oh, I'm being held back in life because of something that I can't help. I was literally just born like this." I didn't want to draw any more attention to my heritage, even though it's very obvious but I really wanted to fit in.

In school. I wanted to fit in. I didn't want my food to be weird anymore. I wanted people to just leave me alone. I really tried very hard to be, "the best American that I could be."

Then, when I lived in Hong Kong, it was kind of the opposite. I was like, "Okay, I'm going go to Hong Kong, and everybody will get me, and I'll be totally fine," but that wasn't the case. I ended up going to a French school, and all my classmates were the kids of wealthy Europeans, they were all French or British. Then I was still too Asian for everybody in Hong Kong somehow. Then the locals just thought I was American. I never felt like I belonged anywhere. I never felt like I had a support system or anybody that could relate to me or that I could relate to.

Alison Stewart: Well, how did going to culinary school lead you to appreciate the foods that you'd grown up with in new ways?

Clarice Lam: I've always appreciated the foods that I grew up with. Those were my little secrets. The little treasures that I held onto from my memories and things like that. Of course, I always eat Chinese food, Korean food, any kind of Asian food. That's my go-to. I think going to culinary school allowed me to go on my path. Then when I first opened The Baking Bean, there wasn't very much Asian influence. I think I didn't really look too deep inside from my former influences until I worked at Kimika because that was an Italian-Japanese restaurant, I really had to think hard.

Then I realized that I was getting a lot of accolades for the things that I was making over there. Then that really encouraged me. I was like, "Oh, now is a good time. People get it now. People are interested in all kinds of Asian foods and different foods, and I'm not going to be weird anymore. They're enjoying it." It was kind of like, "Okay, now I can step back into myself and really share with everybody."

Alison Stewart: My guest is Clarice Lam. The name of her book is Breaking Bao: 88 Bakes and Snacks from Asia and Beyond. First thing I learned, you don't say bao buns, right?

Clarice Lam: I know. That's one of my biggest pet peeves. I really exaggerate my hatred for that just because I think it's funny. You don't say bao buns. Bao in Chinese already means bread so you're basically saying "bread-bread" twice. Like, you're not going to go to a bakery and ask for a baguette bread, it's just redundant. It's like saying chai tea or, you know, espresso coffee or a spaghetti pasta. It's just redundant.

Alison Stewart: Now everybody knows.

Clarice Lam: Now everyone knows.

Alison Stewart: The book contains 88 recipes. 88 is a significant number in Chinese culture. Was there a particular reason you wanted 88? Did you have to stretch to get it to 88? What was the idea?

Clarice Lam: The number eight in Chinese and a lot of other Asian cultures, it stands for good luck. In Chinese, you say fa means good luck, and the way to say the number eight is bā, so it sounds the same. Therefore, eight is a really lucky number. You can only have up to a maximum of three eights, for some reason. Any kind of combination of eights, sixes, ones, and threes, those are all great numbers. My dad was really superstitious about the number eight, so I kind of turned it into a joke in my head where I must have-- I'm not going to do only eight recipes, and I'm not going to do 888 recipes so it's 88. That's it.

Alison Stewart: What's a recipe in the book that reminds you the most of Hong Kong and what's one that reminds you the most of LA?

Clarice Lam: I think the one that reminds me the most of LA is my mom's. My mom is a terrible cook, but she did do one thing very, very well, and that was the coconut baos, or in Cantonese, we call them Gai Mei Baos, which means a chicken butt bun. It doesn't have chicken and there's no butts. It is a milk bread bun that is usually just filled with a rich, delicious, buttery coconut filling. Sometimes you can find it as a spiral.

This is something that on weekends, maybe once a month, my mom, my sister, and I would gather around the table and we would make a whole batch of them and then save them in the freezer and then eat them for breakfast. In my book, I call them Mama Lam's Coconut Croissants. It is her recipe, but I just changed the form of it. Instead of just being a regular bun shape, I used the coconut buttery filling as the butter block. Then I laminated that within the layers of milk bread and then shaped it like a croissant. That for me is LA.

Then Hong Kong is a bolo bao, like my Char Siu Bolo Bao or any bolo bao, which is called a pineapple bun, also doesn't have pineapple. It's the classic yellow bun that you'll see in Chinese bakeries with the yellow kind of crumbly top. It's meant to look like a pineapple rind, so that's why it's called a pineapple bun. That was my favorite thing to get at bakeries when I lived in Hong Kong.

Alison Stewart: One of the things that's really interesting about the book is there's pictures of you making the food. There could be up to 16 pictures of you with the bread, learning how to make the scallion pancakes. Why was it important to put in those detailed pictures?

Clarice Lam: For me, I'm a visual learner. I literally can't learn anything until I see it. I will forget everyone's name until I see it written out or spelled out. I need the visuals in order to understand something. I also don't like cookbooks that don't have at least one photo per recipe because I want to look at it and then decide if I want to make it. You eat with your eyes first. For me, the only way that I would understand how to make something is if I see it in photos. I thought that that would be a good way to explain to people the method.

Alison Stewart: The book includes a recipe, and please correct me if I'm wrong, White Rabbit Sachima.

Clarice Lam: Yes.

Alison Stewart: All right, this is something like a Rice Krispies treat, and it involves this Chinese candy. You write about how the kids made fun of you. They call it now yucking someone's yum. They didn't like your candy initially. First of all, tell me what's in the White Rabbit Sachima, and then why is that candy important to you?

Clarice Lam: Sachima is almost a Chinese version of a Rice Krispies treat. It looks like a Rice Krispies treat, but it is thin sheets of dough that you cut up into strips that look very much like noodles and then you deep fry them. Then they puff up really big. Then you toss them in a very delicious honey-type syrup. Then you pack it into a pan, and then you cut them up into squares so it looks like a Rice Krispies treat.

In my version, I've added the white rabbit candies, which, yes, those are my favorite, most nostalgic Hong Kong candies that I talk about in my introduction, how I brought them to Show and Tell Say in 7th Grade when we had to share our cultures because that's my favorite candy from Hong Kong. I brought it and nobody liked it. They didn't get it. They thought it was weird. Nobody ate my candy, and I was so upset about it.

Alison Stewart: So sad. So sad. Now they'll know. It's interesting in the book that you spend a lot of time explaining flowers, but I don't know if people understand that they can be different. Just basically, what would you describe as the difference that the flours come down to?

Clarice Lam: There's a lot of different flours. Wheat flour is the most common type that you'll find in any supermarket in America. It's cake flour, all-purpose flour, or bread flour. It really has to do with the protein content and the ability to hold the gluten structure. Bread flour, as it says in its name, has the highest protein content and is best for making things like bread. You want that structure, you want it to hold up.

A cake flour has the lowest protein content, and that's good for making things that you want to be tender, like cakes. Then all-purpose flour is what most people buy for everything. Like the name, it's all-purpose. You'll use it for cookies. Sometimes you can use it for some lighter breads, but that's the middle range in the protein content.

Alison Stewart: All right, the easiest recipe in the book, you say, "It's probably the easiest recipe in the book," and dare I say, the yummiest, Thai Tea Gelati. What makes it easy and what makes it yummy?

Clarice Lam: It is definitely the easiest recipe in the book because it's one of those that you-- The ice cream is no churn. It's condensed milk ice cream. You whip it up, it literally takes 10 minutes to make the ice cream. Put it in a quart container, put it in the freezer, and then forget about it. Wait till it freezes, and then you're done.

The same with the Thai tea icy part. It's like a granita. You just basically make a Thai tea with some extra sugar, some citrus, and then you freeze it. Then if you have the time, you can scrape it down every couple of hours with a fork, like a granita, or if you don't have the time, which I've forgotten before, and I've just left the whole thing in the freezer, it forms into a solid block, but because of its sugar content, you're still able to scrape it. Both of these things you can be done within 10 to 15 minutes. Put it in the freezer, forget it, and then when it's frozen, you're ready to serve.

Alison Stewart: The hardest recipe in the book, Dragon's Beard Candy. What's the history behind this recipe and what makes it so hard?

Clarice Lam: Dragon's Beard Candy is a pretty typical or traditional Chinese street food that my sister and I used to love finding on the streets of Hong Kong. I think it's pretty rare now that you can find them. It involves making these blocks, circular donuts of sugar that you heat up to a specific temperature so it's not too hard and it's still pliable. Then you have to coat it in cornstarch, and you just keep pulling and doubling over it and pulling and doubling over. You do this 14 times until you get a million sugar strands and it looks like a dragon's beard.

The traditional way, the filling is with desiccated coconut, black sesame, some peanuts, sugar, and it just kind of gets wrapped around the filling like a little cocoon. The texture is so amazing, it's kind of like cotton candy. You take a bite into it, it melts in your mouth and then you get the nice crunch from the peanuts and the sugar and the sesame. In my book, I made a modern version. I made it with crushed cornflakes, freeze-dried bananas, and coconut.

Alison Stewart: Clarice Lam will be appearing at Pecking House on October 25th, Union Square Market on October 26, and A&C Super in Brooklyn on October 27th. Her new book Breaking Bao: 88 Bakes and Snacks from Asia and Beyond. It's available now. Clarice, thank you so much for joining us.

Clarice Lam: Thank you so much.