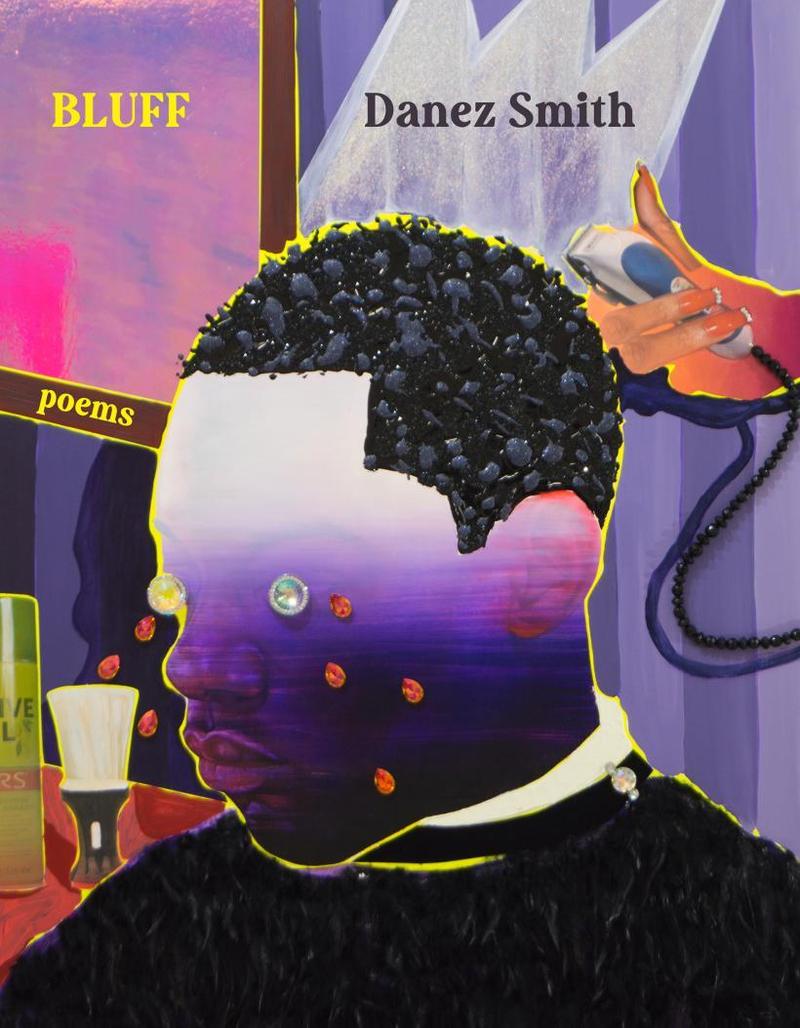

A New Poetry Collection from Danez Smith

( Courtesy of Gray Wolf Press )

Title: A New Poetry Collection from Danez Smith

Kousha Navidar: This is All Of It. I'm Kousha Navidar, in for Allison Stewart today, joining you live from the WNYC Studios in Soho. Thanks for sharing part of your day with us. I'm really grateful that you're here. On today's show, we'll start to wrap up the All Of It summer reading challenge, which asked you, listeners, to read four books in certain categories. Get lit Producer Jordan Lauf will be here to recap what we've all been reading and take your calls with your informal book reports. We'll also learn a bit about boba tea or bubble tea, a taiwanese invention from the '80s that's taken off in the States.

As a refreshing treat, Gabe Bergado, staff editor at The Infatuation, will share some of the history and some of the best local places to pick up a tapioca-filled refreshment. The new FX sitcom English Teacher, starring and created by comedian Brian Jordan Alvarez, follows the titular English Teacher as he tries to relate to kids who are developing their own sense of justice. Alvarez and his co star and writer Stephanie Koenig will tell us all about it. That's all coming up, but first, let's get things started with some poetry.

[music]

Poet and performer Danez Smith is known for their raw and evocative work that speaks directly to the experiences of Black and queer communities in America. In their latest collection of poems, they explore life in the aftermath of George Floyd's murder. The collection is titled Bluff, breaking their two-year period of artistic silence. This mixed media collection excavates deep personal and collective trauma experienced during this pivotal moment in both Minneapolis and in American history to create a narrative that's both haunting and healing.

This collection also reflects on Smith's own experiences during this time, on what it means to feel at ease at home, given the threat of gentrification and navigating feelings of hope, love, and rage. A review in The Guardian states that, "Bluff's vantage point is dark and original, and foregrounds the historical significance of this time of racial reckonings. It's experiential, existential, and perhaps signifies a new era of politically conscious poetry that rejects ideas of individual empowerment in favor of enlightenment.

Danez Smith joins me to discuss now. Some of you might be familiar with their previous collections, including the acclaimed Don't Call Us Dead and Homie, which have earned them accolades, including the forward prize for best collection and the Lambda literary award. Danez, welcome to All Of It.

Danez Smith: Thank you, Kousha, it's so nice to meet you. You have an amazing voice I can listen to you talk all day.

Kousha Navidar: That is very kind of you. I appreciate that. It is reciprocal as well. Wonderful voice, wonderful writing. We're going to hear some of your reading as well before we dive into it. The title Bluff. When I read that, I thought of making a lie. I also thought of cliffs and the drop off point. What does the title Bluff mean to you? Where does it come from?

Danez Smith: For me, I was looking for a bunch of words that had something to do, because when I started to know that it was a book, the two things I could see it was about was language and place, thinking about my relationship to poetry and thinking about my relationship to here in Minneapolis, but also to America and our larger relationship to the globe, and how we are sometimes a very bad neighbor to the rest of the world. I was looking for a word. I thought about address, I thought about many things. Actually, I went to Twitter. People were like, give me words.

Kousha Navidar: You crowdsourced the title of your book [chuckles].

Danez Smith: Sometimes my thinking is so limited, and I think even the book itself is an invitation to collaborate in the future with people. Right. I even wanted to collaborate on the title. Somebody said Bluff, and I'm very grateful that they said Bluff, because, you know, both for what it means in language, what it means as the high point in land. I think I am looking for a higher point to try to see with clear vision the landscape. Also, I love Bluff because I think I'm calling out my own bluff. A lot of the book is self-referential to poems that I've written before in previous collections, and sort of thinking about my own history as a poet, my own complacency as a poet, as American, as citizen of this nation.

I really did want to think about, what does it mean to call somebody on their bluff? What does it mean to look into the self and call out the BS?

Kousha Navidar: Oh, wow. That is one of the best uses of X that I've ever heard, of Twitter. That's a wonderful way to get a book title.

Danez Smith: We still call it Twitter. X is a horrible name.

Kousha Navidar: That's right. Fair enough. Let's hear a little bit from the book. I understand that you've got a couple of readings. There's this one that really struck me. Jesus, be a durag. Would you be up for reading that?

Danez Smith: Yes, I'll read Jesus be a durag. Sure. Sure thing. This is after the incredible poet and musician Jamila Woods, who's currently on tour. You all should catch her.

Jesus, be a durag and be mighty,

Black, saddened savior stretched around my scalp.

Take me in your hand and make me like the water.

Be a way to tell my people I am their people

Sheer cape falling down my neck make me superhero

Captain save a hoe from myself

Rag to make me unragged mornings.

Let me wake up Black and alive and Black and alive

And thinking I'm cute, Lord of lords, be a fence around my fly be shield, be shield, be rock be spell, be dark and lovely magic. Sweet Jesus, if you God, be God. Let whatever reaches toward us to end us slick past.

Let America drown in our waves.

If a bullet must touch us, let it graze soft as a bristle brush

Let us spill no blood on a day we feel beautiful and we be beautiful

Let us know it, be caskets sharp and banned from early caskets

No Black person will die in this poem but

These waves might hurt somebody.

Watch yourself, swim good

Be happy we sleep with these rags on.

I heard a story once

About a boy who brushed his hair for 40 days and 40 nights

And when he finally slept, he forgot to wrap his ocean up.

Same night, mama started crawling from his hairline carrying babies.

Men climbed out his waves like they had just jumped off the boat.

A wet army necromance from naps.

See, this hair is a right kind of holy.

See, it's not hair at all.

On top of our dome, a prayer.

Harrying us home.

Kousha Navidar: Wow, that was Jesus be a durag by Danez Smith. There's so much power in the way that you've written it when I was reading it, but hearing it now, it took on a whole different level. The line, "Let us know it, be casket sharp and band from early caskets." It's so evocative and pressing. To me, it's especially interesting because Bluff comes after a two-year period of artistic silence. In your last poetry collection, Homie, was released in January 2020. What occupied your mind during that time? What did you learn about yourself as both a person and an artist?

Danez Smith: Well, one, I learned that two years, I think, for some people, is not a very long time not to write. For me, I'm so extroverted. I was so prolific that it was shocking to wake up one day and have nothing to say, [laughs] which is fine. I think I was okay for that for a little bit. During the time, I think what preoccupied my mind was action. I saw another murder perpetrated by the cops, an avatar of white supremacy and of nationalist violence happen here. What happened was we were in the middle of the COVID, we were in the middle of lockdown, and so we were able to activate in a way that I don't think we would have been, had not COVID been happening.

While COVID was a tragedy for the whole world, it gave us a moment of pause that I don't know if the world would have ignited had we not been away from our offices, away from our schools in the same way that we had. A lot of it, I was trying to-- part of it was trying to figure out how to bake bread and how to skate. Then once that happened, it was, how can I be here for my community? What does my community need? What are we saying? What are we raging for? What are our hopes and dreams? My mind wasn't near poetry or the need for poetry. What was needed was hands and bodies and meals and safety and water.

I didn't have time to fool with poems. I was very grateful to come back to it because I think it was a long incubation period that when I came back to poems, I was really considering, like, why write these poems? What is the purpose? I think if you read Bluff, I am arguing with myself, what is the utility of this thing? How long can I scream about wanting the world to change? How long can I scream 'Black Lives Matter'? How long can I scream 'Free Palestine' while nothing happens? Yet, we must. Yes, yet we must write, yet we must scream. Yes. We must continue to press towards a future that we know we deserve until it is reached. Let us not become defeated, but also, how can I make some of that frustration useful?

Kousha Navidar: It's interesting to hear you say that you're wondering how long can you scream, but you also said earlier you felt like you woke up with nothing to say? Can you reconcile those two?

Danez Smith: Well, I think so. I think maybe nothing to say because I feel like I'd already said it. Right. My first three books, they say a lot of what I-- I think at the time they were already in my 20s, and so I think I'd said what I needed to say about desire. I think I had screamed to the world that I am alive and deserve to be so. I had yelled at the world that I love my friends and they are what keeps me anchored here to this world, that I had yelled at the world that we are freaking human and deserve to live uninterrupted, that we do not deserve the punishments simply by being-- that the shadow of slavery was long and still very much alive here in the States, and we need to do away with it.

I was like, okay, well, you said it. What else do you say now? I'm grateful to poets like Carl Phillips, who has a fantastic collection of essays called My Trade Is Mystery. He talks in an essay called Silence about the long waiting period from poem to poem, or for any artist, from one making to the next thing you make. Sometimes it's longer, and I think when I read that a couple years ago, it gave me language for what I was going through. I had satisfied what my mind and my urgency needed to say. It wasn't until those two years later, which for me was a long time, but in the long scope of things, maybe it's not, that finally I came back into something new to say, right?

I think silence isn't always horrible. I think for myself, who was such a prolific artist, it was very scary, but sometimes the most necessary thing you have to do as an artist is to live and to listen and to exist and to pay attention, and eventually the language will come.

Kousha Navidar: What was scary about it? What was scary about being silent?

Danez Smith: I'm not a silent person. If you know me in my life, there's always noise. I once tried to say that I thought silence was a great virtue. All of my friends who were in the room looked at me and said, you are out of your mind if you think that's how you are. There's always music, there's always talking, there's always laughing, there's always noise around me. I think I didn't know if I was going to have anything to say again. I didn't know if I was going to have any more poems again. I'd been so prolific, especially coming from the world of spoken word and slam, where if your poem's not hot, you better go back and write a new one for the next week.

It was the first time in my artistic career where for this extended period of time, just nothing wanted to come. I think it's because sometimes the language sits in you and is trying to figure itself out before it comes into the world.

Kousha Navidar: Yes, it can be very difficult to be still, especially when your life has been activity. You know, some people might not know this, but you are a performer and even went to college as a First Wave hip hop and urban art scholar at the University of Wisconsin Madison. It's clear that performance is a huge part of your career. Can you tell us something unique about this experience that shaped the artist you are today?

Danez Smith: Oh, about the First Wave experience?

Kousha Navidar: Yes.

Danez Smith: I love First Wave. If there are any teachers, parents, or young people listening who want to get a free tuition scholarship to go and be around other young artists and sharpen your minds and tools together, definitely give First Wave at the University of Wisconsin a lookout. First Wave was great for me because it put me in community with such great, phenomenal artists who are mentors, but also who are my peers, some of them who are still making incredible art today. Shout out to the rapper Def C.

Shout out to Jasmine Mans. Shout out, Gethsemane Herron, Erica Dickerson, Karl Iglesias. So many wonderful, amazing artists. Ajanaé Dawkins. Oh, my God. So many folks that I got to be in community with. It was great to see other people coming into themselves, that our minds could be catalysts for each other. It made me feel like I was never alone in the art, right? I think that's why there's such a big 'we' and a big community in my art is because for me-- and also, coming from spoken word where poetry doesn't happen in spoken word in a room alone. It happens on the stage. It happens in community, in the cipher, with an audience.

First Wave, I think, further that for me, that even if I was on stage performing alone, it was the help, the critique, sometimes the literal bodies and voices of other folks that were supporting me.

Kousha Navidar: It's that community. Yes. Listeners, we're talking to Danez Smith, the poet of the collection called Bluff: Poems. It was published last Tuesday, August 20th. Danez, one thing I found very interesting and captivating about this collection is actually the formatting and the structure, because it's pretty unique. The poems take different forms. Some are in black boxes and others have specific texts that are emphasized on the page. How do you think about structuring a collection once you've decided that you have enough poems?

Danez Smith: Well, I think it first happens on the poem level. My first allegiance is always just straight to language. Right. What is it that this thing wants to say? At the word level, at the sentence level. I think that's my first allegiance. Sometimes the page is a wonderful thing because it's a canvas as well. Sometimes maybe language either demands or, because I can't really figure it out, I can bring in some of these more visual elements to help enliven the poem and give it body outside of just sound and words. There's a poem about my neighborhood of Rondo in St. Paul where I grew up, that tries to physicalize the--

Rondo was a neighborhood that was split in half. A lot of businesses and homes destroyed when Highway 94 was constructed in the 1950s. I knew I wanted to write a poem about Rondo, and I knew I wanted that freeway to be physicalized in some way. When you read the poem, there's a long black line that stretches across five or six pages that different language interacts with in different ways to represent this interruption of community, and thinking about how we still survived despite that interruption, despite that severing.

Sometimes the language won't do. I'm grateful to poets like Duriel Harris, like Douglas Kearney, like Courtney Faye Taylor, or Airea D. Matthews, so many brilliant poets who show us that there are visual possibilities in the poem, right. If books is going to be the final avenue that put people that are going to receive these poems in, we can do more than just put words in there, right? Books can hold whatever a page can hold. Of course, our poems can be visual as well. There's another brilliant new collection, Black Bell by Alison C. Rollins, which is a phenomenal book of visual poetics as well.

I've been preaching this. I think visual poetics is the next frontier for poetry. It makes sense. We have so many different tools at our hands now. I just kind of use Microsoft Word, but, you know, folks. Oh, my God, you have folks like Anthony Cody who's doing crazy things with the visual poems. Right? Poets are using all the graphic designer skills that we've amassed along the way [laughs].

Kousha Navidar: You use Microsoft Word on these to think about [crosstalk].

Danez Smith: I just use Microsoft Word. Yes, sometimes I'm scanning something. There's a collage in the book, right? I had to figure out how to scan that and do some things with it. Right? All the black boxes and stuff, I'm just in Microsoft Word fooling around. The secret of it is poets have no idea what we're doing.

Kousha Navidar: You also have a QR code in the book to more poems.

Danez Smith: I do have a QR code.

Kousha Navidar: You are multimodal there. I'm so happy that you brought up your community, because in a lot of interviews, you talk about the importance of feeling rooted in the Twin Cities, which is where you're from. You've lived outside the state for some time, but you returned. Can you talk a little bit about how your connection to Minnesota's evolved as you've grown older through the different [crosstalk]?

Danez Smith: For sure. I think I loved Minnesota. I still do. When I was younger, I got itchy, and I started feeling nomadic and had these periods of like, oh, my God, I absolutely need to leave. I need to get out of here [laughs], really for no other reason than that. It's the place it is. I think it hasn't always felt the most welcoming as a young, Black queer person. Right. It's sometimes hard to see mirrors of yourself here, though there is a beautiful queer community here and a Black queer community here. I moved to California. I went to grad school in Michigan. I toured for a long time.

Even while I was in Minneapolis, it kind of felt like I was living a little bit of everywhere. I was on tour maybe half of the year at some point. Actually, when 2020 happened, when the pandemic happened, I was so ready to move. I had applied for this fellowship, had got it, was going to move to the east coast. That was my secret way to get to New York and maybe transition there. Then we were told that we had to sit down. Then even though I had the fellowship, the first year of that was online, and so I didn't want to move to New York if I couldn't go to the club, and I just had to teach on Zoom, so I stayed in Minneapolis.

What happened in the pandemic, in the uprisings after George Floyd's murder, in that year that I had to sit down and really confront and be there with my city, I fell back in love in a way that I think it'd be really hard to pull me away from. There is such a rich tapestry of hope and of possibility here that, oh, my God, if our mayor would just get out the way [laughs], we could have-- I think there's a rich future here. I feel the seeds here, and it's a place maybe because I know it so intimately. It's a place that I feel like I know how to influence and change. I feel such deep and electrifying love when I think about the Twin Cities, and I also critique it. It's not perfect.

I hate our cops and the things they do and the ways they're protected. I think there is a quaint kind of white supremacy that lies under the surface here in Minnesota, that they would like to call Minnesota nice, but sometimes it gets very Minnesota ugly, but I know how to confront it. I think when we talk about changing the world, it can feel so huge to think about changing the entire globe or about how to affect change in a country that we've maybe never been to. All change starts from the micro and that for me is the local. My love for here is also because I feel the tangibility of this place because I know it and it knows me.

Kousha Navidar: It's so interesting to hear how that love that you saw blossom correlates with a period in your life where you feel like you were still for the first time. I just want to point that out. I think that's very interesting. We got a text from a listener that I think you'd enjoy as well. It says, "Rreally enjoying hearing your poet and their potent rhythmic stylings, whether speaking in verse or prose, makes for a fine refuge in this day," so shout out to you, Danez. That's a little bit of love from our listeners. You're talking about confronting things as well. I'm looking at the clock. Before we run out of too much time, I would love to hear what I think was one of the most potent pieces that you've written. It's right in the beginning. It's Anti-Poetica. If you'd be willing to share that with our readers as well, I think they'd love it.

Danez Smith: Oh, Yes. Okay. There's an invisible ending to this that I edited out just because I think the rest of the book says it. I'm about to tell you a lot of things that poems won't do. I'll just tell you the ending right now that isn't there anymore. All change will happen with our own hands, with our own fire and our own love. As I'm telling you what poems can't do, remember that I'm also reminding us that the power is in our own hands.

Anti-poetica. There is no poem greater than feeding someone.

There is no poem wiser than kindness.

There is no poem more important than being good to children.

There is no poem outside love's violent potential for cruelty.

There is no poem that ends grief but nurses it towards light.

There is no poem that isn't jealous of song or murals or wings.

There is no poem free from money's ruin.

No poem in the capitol nor the court.

Most policy rewords a double script.

There is no poem in the law

There is no poem in the West.

There is no poem in the North.

Poems only live south of something,

Meaning beneath and darkened and hot.

There is no poem in winter nor in whiteness.

There are no poems in the landlord's name.

No poem to admonish the state.

No poem with a key to the locks.

No poem to free you.

Kousha Navidar: That was Anti-Poetica from Danez Smith. I didn't even know about that invisible ending that you mentioned about all changes [crosstalk].

Danez Smith: Oh Yes, nobody does.

[laughter]

Kousha Navidar: [crosstalk] [unintelligible 00:23:59] with your own hands. I think that's really important to bring up as well, because you're talking about what poems maybe can't do, but you're saying here as well, there is still change. I think change-- you're talking about how it comes through local action. Your action is writing poems and so many other things. I'm wondering for you, in the minute or so that we have left here, how do you want readers to engage with these poems? What ideas do you want them to linger with as they navigate their lives?

Danez Smith: I want particularly American readers, readers in Europe or any place of privilege to think about what have been the conditions for our comfort. Who has suffered for our complacency, for our comfort. What is an action that you can take in your daily life to make the world better for somebody else? What are the questions maybe that we're avoiding asking that would rupture our lives but create more possibility everywhere? Can we question the structures that were told are finite? Can we shake our foundation and dream something bigger and newer and freer for everyone?

Kousha Navidar: Poet, author and performer Danez Smith's latest poetry collection. It's titled Bluff. It is out now. Danez, thank you so much for coming on. Thank you for those readings and most of all thank you for this work. We really appreciate it.

Danez Smith: Thank you so much for the time. This has been great. My eternal blessings-- or blessings? Blessings. I don't have blessings to give.

Kousha Navidar: [laughs] We feel the love. Thanks. Danez.

Copyright © 2024 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.