A New Art Exhibit Explores the Vastness of LGBTQ Life

[music]

Kousha Navidar: This is All Of It. I'm Kousha Navidar, in for Alison Stewart. The Leslie Lohman Museum of Art is a living archive of queer history. Ever since its conception in the 1960s, the museum which is in Soho has amassed an art collection of over 25,000 pieces. Each piece tells a unique story about the LGBTQ experience and no single piece of art there is the same.

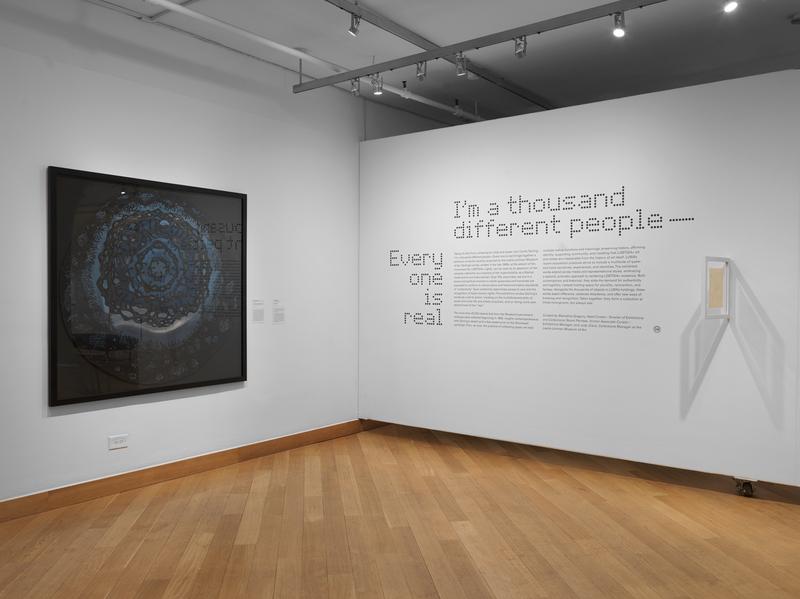

A new exhibit at the museum embraces this ethos. It's called I'm a thousand different people. Every one is real. It's a quote from the iconic trans entertainer, Candy Darling from the 1960s. She was a muse of the Velvet Underground and even starred in Andy Warhol films. Just like Candy's quote, this exhibit contains multitudes. It features a series of digital art, there's oil paintings, sculptures, photographs, just to name a few. It's a beautiful mosaic of artistic expression. With us today to talk about the exhibit is its head curator, Stamatina Gregory. Hi, Stamatina.

Stamatina Gregory: Hi.

Kousha Navidar: We've also got artists Carlos Motta and Angela Dufresne whose works are part of the exhibition. Hi, both. Welcome to All Of It.

Angela Dufresne: Hello.

Carlos Motta: Thank you for having us.

Kousha Navidar: Absolutely. It's a pleasure to have you here.

Angela Dufresne: Thank you.

Kousha Navidar: Let's dive right into the exhibit. The first thing you see when you enter the exhibit is a piece of yellow legal paper hanging on the wall. It's drawn by Candy Darling and there are sketches of women wearing dresses. On top of the page, she writes the words, "A thousand different people. Every one is real." Stamatina, when you first saw this piece of legal paper, did you know this quote would be the centerpiece of the exhibit?

Stamatina Gregory: When this piece entered our collection, which had been sometime about 18 months ago, I did not know that. The conceiving of this exhibition came a short while after the piece entered our collection and really the way in which it came together in terms of looking at that piece, thinking about the significant evolution and shifts and how we can see that and build our collections at the museums.

Thinking about how we diversify and add to, as you said, the 25,000 objects in our collection, which is very unusual for a small museum, really, this show of recent acquisitions came from a desire to communicate our collecting practice, which has really evolved over the past few years. Which really has expanded definitions of queerness, queer art, what folks are making, and how we are building communities through curating. When the show was conceived, oh, go ahead.

Kousha Navidar: No, no. Can you tell me a little bit more about who Candy Darling was?

Stamatina Gregory: Candy Darling was a Warhol muse. That's what she was best known for, but was also a celebrity in her own right. She grew up in Long Island. She moved to Greenwich Village when she was around 17. She met Warhol in 1967 and Warhol cast her in several of his films. Darling, in her time, in the mid to late '60s, the early '70s, she was an SP incarnate in a lineage of queer people, trans folks that were out in public life and was really negotiating, I think, this identity.

I, together with the other curators of the exhibition, my former associate curator Nolan Parnassus, and our current collections manager, Judy Gira, were looking at this piece and thinking, okay, we want this piece to be in the show. Really believing that at that moment in Candy's scroll on this yellow legal paper that in there, we had to-- thinking about the queer archive is always an exercise of speculation.

You will never know exactly. You have only fragments of works and thoughts from our elders in our communities, but we had to imagine that. She was thinking about negotiating this identity publicly and privately and all of the demands for authenticity and particular ways of being that are demanded currently of queer and trans people, Candy be was negotiating the also and saying, "You know what? I am many. I am a multitude. I am a thousand different people. All of us are real."

Kousha Navidar: We hear and see this in a lot of different ways in the exhibit. Listeners, if you're just joining us, we're talking about a new multimedia art exhibit at Leslie-Lohman Museum of Art in Soho. It's titled, I'm a thousand different people. Every one is real. We're here with Stamatina Gregory, the curator. Carlos Motta, and Angela Dufresne who are two of the artists. Carlos, I'd love to get into your work. You have two works exhibited, both are video installations and both feature one individual. The individual's name is Tiamat Legion Medusa. Can you tell us a bit more about how you met Tiamat?

Carlos Motta: Yes. Again, thank you for having me. I met Tiamat randomly at our gay bar in Los Angeles in 2019. Tiamat is somebody who is hard to miss when they enter the room because they have a striking physique. Tiamat has been undergoing several body transformations to become the mythological creature of the dragon. That is the person that I became friends with and started to collaborate with on these two works that are in the exhibit.

Kousha Navidar: What really compelled me about Tiamat was from the one video that explains its life. Tiamat who goes by its pronouns heavily modified its body, horns poking out of its head, tattoos of scales all over its skin. Can you talk us through this transformation? The exhibit calls it a metamorphosis.

Carlos Motta: Well, it wouldn't be better for Tiamat to do that itself, of course, but from the perspective of the story as it was told to me by Tiamat. Tiamat is interested in not dying in the body of a human being because it has faced so many challenges as human in the world. Tiamat is interested in creating a new sense of body relationship and identification that renounces the constraints and the normative categorizations of gender and others in the world. These transformations are really an attempt at practicing the ways in which it is experiencing life as we know it and creating a different relationship that draws from myths and from fantasy and from just a self-realization that will become something different. [crosstalk]

Kousha Navidar: Sorry. Please go ahead.

Carlos Motta: No. I was just going to say that work is titled, When I Leave this World and this is a quote directly from Tiamat in the work where it is saying that when I leave this world, I don't want to die in the body of a human.

Kousha Navidar: Those words that you said Tiamat say to you, I have the quote here. It's, "I did not want to die as a human because of the pain and suffering that humans have done to me in this life." When you first heard Tiamat say those words, how did that sit with you?

Carlos Motta: I think it's, of course, a painful realization to understand the ways in which Tiamat or somebody who has defined itself in a different experience of life through identification and gender expression and body expression, and so on. It just reinforces the ways in which otherness is constantly sidetracked and marginalized and discriminated in our societies. I think that this work is an attempt at centering the ways in which difference should be a possibility and not a negation.

Kousha Navidar: Walk us through the video a little bit. Tell us about what we see how that echoes the emotional and cerebral experience that you wanted viewers to have.

Carlos Motta: There are two videos that make this work. The first one is a performance-pierce video that Tiamat and I did together. It is a two-person performance with the assistance of some people who assisted with the suspensions. One of them is a suspension by hook. Tiamat is an experienced performer doing suspensions by hook. That means that it has performed pierce to suspensions in its body. One of them, the video presents Tiamat being suspended by 10 hooks all in the front of its body.

It is a documentation of the action but with a poetic and musical twist. It allows you to imagine the ways in which transcending gravity or transcendent being in the world would feel like for Tiamat. At the point in which Tiamat is already suspended in the air, I join in the suspension by bondage, which is something I have done performatively as well.

That video results in both of us being suspended in the air, in different ways. The other piece is a more documentary-style video portrait where Tiamat tells its story from childhood to the present, and also reflecting upon its work as a performer, its relationship to its family, and ultimately, also, its relationship to the form of suspension as a way of thinking about pain and the transcendence of pain, both in a allegorical way, but also in a literal way. Both pieces together make a double portrait of the artist.

Kousha Navidar: Stamatina, when you experienced these videos and Tiamat's experience, what was your thought? Why were you drawn to it to include in this exhibit?

Stamatina Gregory: I have been familiar with Carlos's work for many years. I think, Carlos, how long have we known one another? Maybe 18 years?

Carlos Motta: Probably, yes.

Stamatina Gregory: We have worked together in the past, and Carlos had told me over lunch one day about this meeting Tiamat and the extraordinary being that Tiamat is. I had really been looking forward to experiencing this piece. When I did, and I saw it together with my director here at the museum, Alyssa Nitchun, after seeing it and being incredibly moved, we mutually agreed this is a work that needs to be in our collection, in part because it really stretches this notion of queerness and queer liberation and bodily autonomy precisely beyond the ways in which we often articulate it in terms of human rights, in terms of the human, in terms that evolve around particular conceptions of the politics of bodies.

For us, this was queerness stretched and expanded beyond the human in a way that is incredibly interesting and thought-provoking, aside from the fact that it is a beautifully made video and incredibly moving. Folks that have visited the exhibition, this is one of the most talked about works in the exhibition, and so many people have come to us, have come to our visitor experience, people talking about how moved they were by the piece. Of course, when we put the exhibition together, we had to include it.

Kousha Navidar: Can you tell me more about what moves visitors to the exhibit about the piece? I myself watched it, and I was moved, so I can tell you that idea of what you were talking about, Stamatina, about seeing not just pain, but the body shaped beyond ways in which we originally think about it every day with just music and watching this almost acrobatic dance was very moving, for me, at least. What was it that you're hearing from other folks, especially in relation to the exhibit as a whole? What emotions do you find it brings up for people?

Stamatina Gregory: I think for some folks, people have talked about how rarely the art moves them to tears in a contemporary art space. Tiamat talking about its life, of course, the way in which it tells its story, you really feel like you were there experiencing this level of pain and also experiencing forms of joy. There is also something to practices of bondage, suspension, piercing and needle play, all of which are very intently on display in this work. You are very close to their bodies that are undergoing this kind of pain and also a pleasure and joy and to even watch it, I think, elicit the somatic experience in people.

Kousha Navidar: Listeners, if you're just joining us, we're talking about a new multimedia art exhibit at Leslie-Lohman Museum of Art in Soho. It's titled I'm a Thousand Different People. Everyone is Real. We're here with the Curator Stamatina Gregory. Carlos Motta and Angela Dufresne. Angela, thank you so much for being patient while we talk about some of the work here, but I would love to get to your work as well, because right across from Carlos's work is Angela's. It's a pretty large oil painting on a horizontal canvas.

It's mostly a pale light green color, and you see two figures. One is sitting in front of a TV as he is holding a remote control, and the other is a woman standing further away, ironing clothes and looking at him. Angela, can you share the title of your work? It's long. It has a full name to it.

Angela Dufresne: Thanks for having me. I could listen to these two talk all day, so there's no patience involved. It's actually a very early version of an iPhone. It's an iPhone one or something like that. It's not actually a remote control. It's basically me and my gay husband. I'm going to insert in there that I'm not a big fan of gay marriage. [unintelligible 00:16:32], in-- Actually, I'm not going to verbatim remember the title of this painting, but it's in The Man Who Fell to Earth.

It's a film that as a Queer person, I was struck by because-- It's David Bowie is an alien that comes to Earth, and is trying to accomplish a mission that's very much an ecological mission and fails miserably because he gets sucked into the vortex of mediated personality construction in the mid-'70s television era. He gets lost, he loses the memo. I was really interested in that as someone who, growing up in the midwest, inherited a very tedious version of heteronormativity. Seeing Bowie, who was an absolute icon of mine, jumping on my brother's bed, listening to Changes One over and over and over again as a teenager was, like many, a lifesaver.

Witnessing this film felt more than just that fan girl experience. It felt witnessing somebody who was unable, in a way, to eject themselves from the cycle of the normative construction psychologically of the mediated apparatus. I made a painting about it. There's something else more, but I made many paintings about it during this series, I guess you could say I'm still making paintings about it, which encapsulates the kind of studio and the domestic space, and it conflates the two into a generative space where different kinds of familiar structures can be embodied, in particular, queer expanded notions of family. I did a series of multiple paintings about non-normative family structures.

Kousha Navidar: Angela, let me pause you right there. We're going to take a quick break, but I want to dive more into it. We're talking about the new multimedia art exhibit at Leslie-Lohman Museum of Art in Soho. It's I'm a thousand different people. Everyone is real. We have the curator, we have artists on here. When we come back, I want to dive more into this piece and look at it as a whole at the exhibit. This is All Of It. We'll be back. Stay with us.

[music]

Kousha Navidar: This is All Of It from WNYC. I'm Kousha Navidar. We got a lot of people that we got to talk to today.

Angela Dufresne: You're a million people, the only one.

Kousha Navidar: We all contain multitudes, folks. This is wonderful. We're talking about a new multimedia art exhibit at Leslie-Lohman Museum of Art in Soho. It's I'm a thousand different people. Everyone is real. Maybe I'm channeling that right now. We're here with guest, Stamatina Gregory, who's the curator. Carlos Motta, who's one of the artists, as well as Angela Dufresne, who's also one of the artists. Angela, before the break, you mentioned that idea of heteronormative conformity that you experienced in the Midwest.

It's interesting because in the opening blurb of the exhibit, there's a line that I want your reaction to. It's saying, "We are in a socio-political moment in which queerness and transness are expected to conform to cis-normative and heteronormative standards of authenticity." Can you talk a little bit about your artwork, how it recreates but also transmutes a domestic suburban theme with relation to what that quote is?

Angela Dufresne: I don't know if it transmits that suburban theme. Maybe this one does. I think to a certain extent, it has to do with the fact that queer emancipation becomes more and more about a indoctrination or an assimilation into normal social structures. There have been much meaningful advocacy for a more flexible, generative, and expansive way of living and carrying and supporting for each other that aren't necessarily the conventional notions of marriage and property ownership and nation state and things like that, that as access becomes more readily available to queer folk, has been the accepting notion of success and prospering.

The archive was mentioned before, and many of the citations in that painting are from archives that are artists that not only would have never embraced those kinds of normative modalities, but that to a certain extent are being forgotten that I want to look at as ways of living that are different than the normative attitude that is imposed on all of us that is so limiting and extra-active.

Kousha Navidar: Samatina, is there any other artwork in the exhibit that you'd like to shout out that you think fits into these themes particularly well?

Stamatina Gregory: There are so many. First of all, I just want to say I'm so thrilled, [unintelligible 00:22:23], to have your work in the show and to have your work in our collection after you've been part of the fabric of the museum for so long. This piece is really extraordinary. It's very hard to come up with a theme for a show of recent acquisitions, which, by its nature, has a biennial format in which you have something that holds a theme that is very expansive.

This, Candy's quote and this theme really encapsulates this struggle that queer and trans communities are in at the moment. The more you think about it, the more you can read it into so many of these works. For example, Tommy Kha, an incredible artist who works primarily in photography, who works between Brooklyn and his hometown of Memphis. We have two works from a series of works that he made in collaboration with--

Stamatina Gregory: Samatina, I'm going to have to pause it there. I'm so sorry, but I hope that folks can go check that out. It's a new multimedia art exhibit at Leslie-Lohman Museum of Art in Soho. It's called I'm a thousand different people. Every one is real.

Copyright © 2024 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.