A History of Ward's Island Told Through Marginalized New Yorkers Sent to Live There

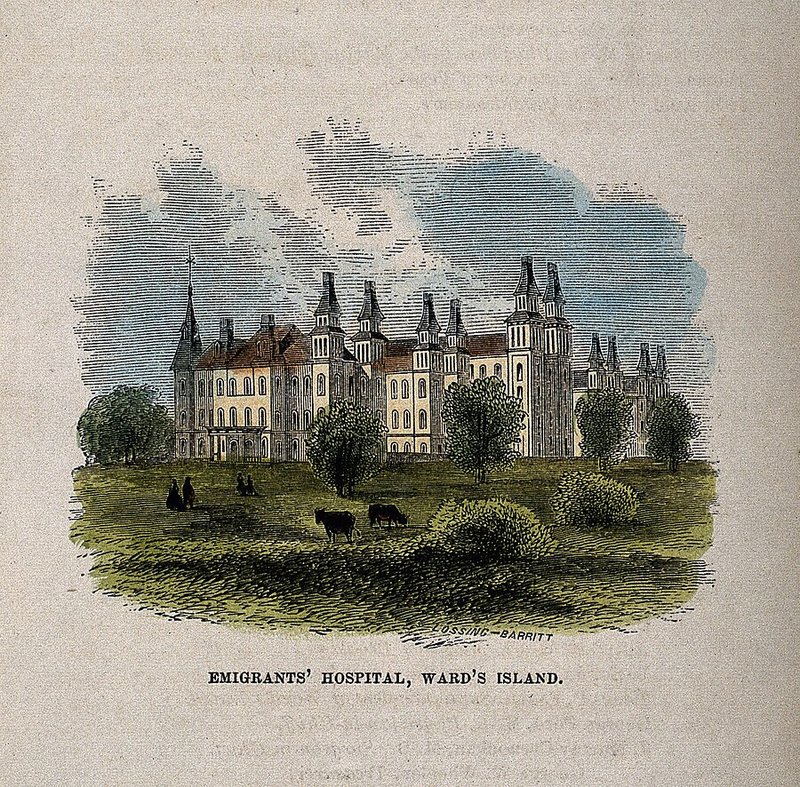

( Coloured wood engraving by Lossing-Barritt. Courtesy of Iconographic Collections (CC) )

Alison Stewart: This is All Of It on WNYC. I'm Alison Stewart. For almost 200 years, New York has used Ward's Island to house its most marginalized residents. Over 1,000 people live on the island today. Many of them are patients in psychiatric hospitals, homeless shelters, community residences, and a substance abuse program, not to mention a migrant shelter that was recently closed. Our guest says there isn't another island like it in North America, and yet many New Yorkers have never heard of Ward's Island.

Philip T. Yanos grew up on Ward's Island for 10 years because his dad was a psychiatrist for an island hospital. Philip followed in his dad's footsteps. He's a professor of psychology at the John Jay College of Criminal Justice and the CUNY Graduate Center. He's worked with patients on Ward's Island. Philip has written a new book called Exiles in New York City: Warehousing the Marginalized on Ward's Island. He writes in the book, "I believe it is time for New York City to come to terms with the way it has been using Ward's Island as a dumping ground for marginalized groups for the past 180 years and take explicit steps to make amends for its past and current injustices.

Philip Yanos is with me now in studio to discuss his research. He has a book event at the Word Up Community Bookshop at 2113 Amsterdam Avenue on Saturday, May 3rd at 3:00 PM. He joins us now in studio. It is so nice to meet you.

Philip T. Yanos: I'm very, very honored to be here. Thank you so much for having me.

Alison Stewart: Considering that in your book, you found that many New Yorkers don't know about Ward's Island, let's start simple. What is Ward's Island?

Philip T. Yanos: Ward's Island is a landmass that's in the East River between East Harlem and Astoria (Queens), roughly opposite 99th Street, 215th Street. Most people who interact with it either interact with it because they're going over it on the overpass of the Triborough RFK Bridge. If they're going from Manhattan to Queens, that's what they would go over, or they interact with it through the sports programs that operate there. There's a lot of fields that are used for sports programs. Most people kind of have this dim sense that there's institutions that might have been there at one time, but they don't know that they're still very much active.

Alison Stewart: Before we get into the history, what services still exist for people in Ward's Island? Approximately how many people are there?

Philip T. Yanos: It's about 1,300 people. There's two hospitals, Manhattan Psychiatric Center and Kirby Forensic Psychiatric Center. There's two homeless shelters, the Keener Shelter and the Clark Thomas Shelter. There's two community residences and there's the Odyssey House Residential Substance Use Treatment Program.

Alison Stewart: You write in your book, "More than 100,000 cars drive over Ward's Island every day on the Triborough Bridge overpass," yet a lot of people haven't ever heard of it. Why do you think that is?

Philip T. Yanos: Well, another part of it is that there's been a rebranding effort in the last, let's say 10, 15 years where Ward's Island's identity has been subsumed by Randall's Island, which is a neighboring island that it got connected to by landfill. Largely, people are only thinking about the Randall's Island aspect, which is recreational and not about the fact that there are people who are still warehoused there and are very much cut off from life in New York City.

Alison Stewart: Also, I want to get into your story. You spent time there as a child. What do you remember?

Philip T. Yanos: Well, the memories are mostly very good. It was not very-- not a lot of people went there outside of the people who worked in the hospital in those days, even though it already been converted to parkland, but it was very underused. I have a lot of very nice memories from my childhood. In the book, I talk about seeing a sky full of stars when the '77 blackout happened. That was quite memorable. Never forget seeing stars in New York City like that.

I also remember the filming of the movie, Godspell. If anybody remembers the movie, but came out in 1973, it's sort of a Jesus Christ-superstar-type movie. The culminating scene where the Jesus character is crucified on a fence that was filmed on Ward's Island. We went and watched that happening. Then just a lot of days playing baseball drills with my brother and our friend, Hiram. We were pretty much the only ones there to play together and we couldn't play a full baseball game, so we did all these different drills to just amuse ourselves. Things like that.

Alison Stewart: When did you start to realize Ward Island's history within New York City? During your graduate time or when you were in school?

Philip T. Yanos: Honestly, I really hadn't looked into it much until I really started to dig in for this book. I didn't know when the New York City Asylum for the Insane had opened or the immigrant refuge that existed before. I didn't know about that until I started researching for this book. What I knew was that it was something that was off people's radar, and I felt that that was unjust because the people who live there deserve to be paid attention to.

Alison Stewart: My guest is Philip Yanos, professor of psychology at the John Jay College of Criminal Justice and CUNY Graduate Center. We're speaking about his book, Exiles in New York City: Warehousing the Marginalized on Ward's Island. If you'd like to join this conversation, our number is 212-433-9692. Are you like Philip and spent time on Ward's Island, maybe as an employee, or a patient, or a resident of one of its shelters? What was it like for you? 212-433-9692. 212-433-WNYC. You tell us a fully recorded history of Ward's Island from the early 1600s to the present. When did Ward's Island first become a space for the city's most marginalized New Yorkers?

Philip T. Yanos: Right. The pivotal event was in 1847 when there was going to be this immigrant refuge built in Astoria, which was not part of New York City yet, but the city had some jurisdiction over, and the residents of the community found out about it, and they went and they destroyed the building. At least this is the story that I've read. The city hastily had to come up with another location where there wouldn't be this kind of community opposition to immigrants. They purchased land on Ward's Island, and by 1848, they built this immigrant refuge and hospital. It was a lot of the services that ended up being located on Ellis Island, but it was there until the 1890s, so it lasted for quite some time.

Alison Stewart: Ward's Island has had the state immigrant refugees, asylums, psychiatric hospitals. What does Ward's Island-- what does it represent about how historically New Yorker has treated its most marginalized residents?

Philip T. Yanos: Well, I think what I found and what we see from this history is that the NIMBY phenomenon that--

Alison Stewart: Not in my backyard.

Philip T. Yanos: Yes. That we've started to talk about in the last 50 years or so, really goes back 200 years. Part of it is that New York is a densely populated place, and people have reacted to groups that they don't want to have near them, whether they be immigrants from Ireland and Germany in those days or from South America now. They are looking for a place to send people so they can not have community opposition. Blackwell's Island, which became Roosevelt Island, was another place where that happened, but it no longer has any such institutions. Ward's Island still does, very much so.

Alison Stewart: Let's take a few calls. This is Herbert, who is calling in from the Bronx. Herbert, thank you for taking the time to call All Of It today. You are on the air.

Herbert: Good afternoon. Oh, yes, good afternoon, ma'am. [chuckles] I was a patient at one time in Ward's Island in the Kirby Building and then in MCTC, they called it. Manhattan Children Treatment Center. I was there from about 1970 to about 1975.

Alison Stewart: What was your experience like? What was your experience like?

Herbert: Oh. What I can remember, you got to remember I was a child at that time. I basically grew up over there. It was good. The people that worked, they treated us good. They tried to do the best. A lot of us would just throw away. Kind of hard, but it was a good place. I can't say they beat me. A lot of people was on medication there, so everybody walk around the days somewhat. Then again, this was in the '70s, though, not today. I don't know what's going on over here today. I know they got shelters over there or something else, some drug programs, but I'm talking about early '70s.

Alison Stewart: Herbert, thank you so much for calling in. We really appreciate you sharing your experience. Let's talk to Kathy, who is calling in from Manhattan. Hi, Kathy, you're on the air.

Kathy: Hi. I just wondered, I was a social work intern at Hunter College in 1970, and I worked under a social work supervisor and I witnessed a lobotomy there-- lobotomy hearing is what I'm trying to say. My point is that at that time, all it was ever known for was a state mental institution and once you were committed there, you couldn't get out. It wasn't anything more than that. When did it change that all these other facilities started showing up on--

Alison Stewart: When these people started showing up, Philip?

Philip T. Yanos: Yes. I can speak to that. Some of the expansion happened in the early '70s. The previous caller mentioned Manhattan Children's Psychiatric Center, that was a new building that was built in the early '70s. Then what really changed the character of it was the opening of the first homeless shelter in the Keener Building in 1980. That really was part of the story of New York City's response to increases in homelessness that were being observed in the Bowery, where the traditional men's shelter had been.

The Keener Building was named in the Callahan consent decree that came out of the lawsuit from the Coalition of the Homeless, what became the Coalition of the Homeless of the City and the State. It was named as one of three places that people could live.

Alison Stewart: Was it the right for men to have a place to stay?

Philip T. Yanos: Yes. It was a right to shelter that we still have to this day in New York City. Then the opening of the Keener Building was the beginning of that expansion. Where the Clark Thomas Shelter is now is the same structure that used to house Manhattan Children's Psychiatric Center, which was closed in the '90s under Gov. Pataki.

Alison Stewart: Here's a question for you. This is one I had to. Isn't Randall's Island and Ward island one island? What's the difference? When and why did they divide them?

Philip T. Yanos: Well, they were two separate islands. They were separated by what's called the Little Hell Gate Passage. Robert Moses built a bridge between them after he created the overpass for the Triborough Bridge. Then they were joined by landfill sometime in the early '70s. The landfill conjoined aspect was there when I was living there, but they were never referred to as a single island then.

The whole thing of referring to them as a single island really started in the 2000s. I believe that that was connected to this rebranding initiative from the Randall's Island Park Alliance, which has funds to support the upgrading of the park facilities on the island.

Alison Stewart: You brought up Robert Moses. Everything goes back to Robert Moses at some point. When he took an interest in Ward's Island, I think it was in the 1920s, what was his original vision for Ward's Island?

Philip T. Yanos: His vision was that all institutions would be gone, that the buildings would be raised, that 100% of the island would become parkland. That was his vision. At the time, the hospital was not far from its high point of census of about 8,000. There had to be a dramatic reduction of the number of people and removal of people to other institutions. His idea was that they would go to Suffolk County, to other places far away from New York City, that they didn't need to be close to where they came from.

Alison Stewart: Let's take another call. This is Theresa calling from Midtown. Hi, Theresa, thank you so much for calling All Of It. You're on the air.

Theresa: Hi. Thank you. I have some positive things to say about Ward's Island. First of all, I actually had to google it because I had not heard of it. I know it as Randall's Island. You learn something new every day. I live in Astoria and I'm an avid biker, and I often bike over the Triborough Bridge and I pass through the entire island, and there's beautiful waterfront parks there, and it's really pretty. Then I get what I know now is the Ward's Island Bridge that goes to East 105th street in Manhattan and continue my ride. I always knew it as Randall's Island, and there's the stadium now, Icahn Stadium. I was unaware of all the other aspects of it that I'm hearing now. Thank you for that.

Alison Stewart: It's interesting. Thank you so much for calling. It's what you call the dual identity. Tell us a little bit more about that.

Philip T. Yanos: This caller speaks to the fact that it is this beautiful place, and that's something that I emphasize in the book as well, and that this place that New Yorkers can come to ride a bike and to play sports is a wonderful thing. Something that I speak about in the book is that the people who live there should also be able to use those facilities, and they have a right to it as much as any other New Yorkers. There's an unjust situation where they're fenced in. The one thing that they have there that could be theirs because they have nothing else there is something they're kept from, and I think that that's unjust.

Alison Stewart: My guest is Philip Yanos, professor of psychology at John Jay College of Criminal Justice and CUNY Graduate Center. We're speaking about his book, Exiles in New York City: Warehousing the Marginalized on Ward's Island. Let's take a call from Susanna from the East Village, who I think has a question for you, Philip. Hi, Susanna, what's your question?

Susanna: Hi, Alison. Thank you for taking my call. My grandmother was interned at or was institutionalized at Ward's Island for a good 20 years of her life, which pretty much took away her life. That's what they did in the '60s and '70s, they just put people away. Exactly what you're saying. They would never see the light of day again. I visited her as a child. I was probably about the same age as you. I'm wondering, how can we access her record?

Alison Stewart: Do you know if that's possible?

Philip T. Yanos: I do not. I can say that the archives of New York State that are held in Albany do have a system by which you can request records of patients. That was an option that I considered when I was reviewing records in various places. It is possible that a family member could do that. I was told that the process is quite lengthy and involved, but those records do exist and could potentially be requested by a family member. I would look online under the New York State Archives, and those are held in Albany, not far from the Capitol.

Alison Stewart: Good luck to you, Susanna. Let's talk to Diana from the Upper West Side. Thank you so much for taking the time to call All Of It.

Diana: Oh, thank you, Alison. Thanks, Professor. I'm really interested in reading your book. Looking forward to it. I wanted to mention that I was an intern on Ward's Island. We called it Manhattan State in the mid-'90s. The comment I want to make is that I learned so much from the people that I saw there. Had a chance to get to know quite well in one-on-one connections through testing, observation, assessments, et cetera, as well as groups and others. What I gleaned, what I learned, it just feels like it-- I just want to honor the people that I had the privilege of working with out there but meeting the patients.

When I left the internship, there was a keen awareness on my part that the folks that I saw there that had been there for such a long while and would continue to be, that this really is the word you use, "A warehouse" for them, that there really was. This was the last stop. We live in Manhattan, as was mentioned, and when I drive by to go out to the island, to go to the airport, I always point out and mention to my kids that this is what this is, let's not forget. Let's just not forget. Thanks, Alison. Thanks, Professor. I appreciate it.

Alison Stewart: Appreciate you, Diana. You closed the book with seven proposals for a better future for Ward's Island, including public transportation access, consolidating hospital buildings, constructing housing. Which of these proposals do you think are the most urgent or could be the most immediately effective?

Philip T. Yanos: Well, they're all kind of connected. Largely what I'm saying is that we have this area where the campus of Manhattan Psychiatric Center is, where it's actually zoned residential and we could build housing there. The hospital itself is underused. There's only about 400 people between the three buildings, including Kirby and PC, and they could all be in one building. We could demolish two of them and build affordable housing that could be a place where people who live in the shelters currently could live. There could also be affordable housing for other low-income New Yorkers.

We could also create amenities, because currently there are none. There's no grocery store, there's no pharmacy, there's no place to eat. Those things could be included as part of the plan. If we increase the frequency of the M35 bus, which is the only way on and off the island currently, and had routes that went to Queens and the Bronx, which are possible because of the Triborough Bridge, then that would increase access to it and it would be good for everyone who's visiting it too. They would be able to get there more easily from other places, and they would also be able to take advantage of these amenities and interact with people who live there, and see that these are human beings.

Alison Stewart: We've been speaking about the book, Exiles in New York City: Warehousing the Marginalized on Ward's Island. It is by Philip Yanos. Philip has a book event at the Word Up Community Bookshop at 2113 Amsterdam Avenue on Saturday, May 3rd at 3:00 PM. Thank you so much for joining us on WNYC.

Philip T. Yanos: Once again, thanks so much for having me. Great honor.

[music]

Alison Stewart: Coming up, we'll take a hands-on approach to history. Max Miller runs the YouTube channel Tasting History. It's now a cookbook of the same name, and he joins us to talk about his passion for history. That's coming up after the news.