A History of Horror in American Culture

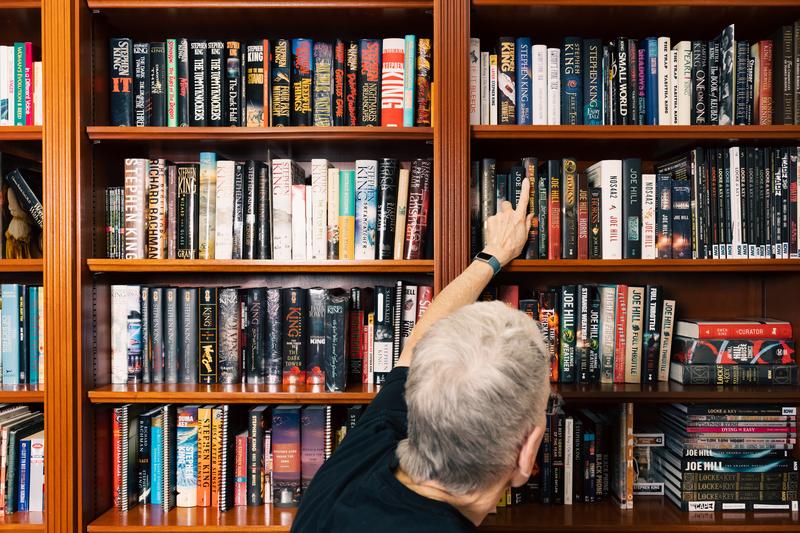

( Photo by Tristan Spinski for The Washington Post via Getty Images )

[music]

Alison Stewart: This is All Of It. I'm Alison Stewart live from the WNYC studios in Soho. Happy Halloween. Thanks for spending part of your day with us. I'm really grateful you're here. I'm especially grateful to everyone who came out to the New York Public Library for our Get Lit with All Of It book club event. We spoke to author Dinaw Mengestu, and then experienced a book club. First, we had a dance party. We danced in the isles with musician, Angélique Kidjo. It was wild, not to mention a whole lot of fun. You'll hear some of the highlights on our show soon, and go see Angélique at Carnegie hall this weekend. On today's show, director Erin Lee Carr will be here to talk about her new documentary, Fanatical: The Catfishing of Tegan and Sara. We'll speak about the legacy of the movie the Texas Chainsaw Massacre, and we'll learn about the life of the mysterious rapper MF Doom from the author of the book The Chronicles of DOOM: Unraveling Rap's Masked Iconoclast. That's the plan for today. Let's get this terrifying show started.

[laughter]

Alison Stewart: To celebrate this spooky occasion, we're talking about some of the writers, artists, and filmmakers who have terrified us for centuries. A new book traces the role that horror has played in American culture. In the book, American Scary: A History of Horror, from Salem to Stephen King and Beyond, author Jeremy Dauber writes, "Show me what scares you, and I'll show you your soul." The 418-page book examines how real fears shaped American horror stories from the Puritan preachers threats, to eternal damnation, to Jordan Peele's scientific horror films that touch on race. Author Jeremy Dauber joins us to discuss. He's a professor of Jewish Literature and American Studies at Columbia University. Hi, Jeremy.

Jeremy Dauber: Hi. It's so great to be here. Thank you for having me.

Alison Stewart: Listeners, we're talking about our culture's fascination with unsettling thoughts and things that go bump in the night. Are you a horror fanatic? What are some of your favorite scary stories or books? What do you get out of reading horror or being scared? How'd you first become interested in the genre? Do you remember the first horror novel you read? How old were you? How did you react? Our phone lines are wide open. 212-433-WNYC. 212-433-9692. Or you can reach out to us on social media @allofitwnyc. You can call in or text us at 212-433-9692, 212-433-WNYC. Jeremy, how do you define horror as a genre for the purposes of this book?

Jeremy Dauber: Well, that's a great question. I started out just by asking the question, what has scared Americans? Just what scared them from the very beginnings to the present day. Then I took that as my guiding star and basically divided it into different kinds of categories, but really what it came up is that what we might call true horror and fictional horror, it's really much blurrier than we might think. That was the fun thing to track throughout the story.

Alison Stewart: What was the first novel or movie that you remember thinking, this is terrifying?

Jeremy Dauber: Well, it's funny. The first thing that I remember is being in the schoolyard at kindergarten, the recess yard, and reading some small children's book about a vampire with the phrase, "Something is amiss and out of place when a bat with wings can have a human face." There was this illustration of this bat with a human face. Probably now it would be silly, but that had me going for, I don't know, years.

[laughter]

Jeremy Dauber: Then subsequently, Stephen King, but first, that bat with a human face.

Alison Stewart: What is it about Stephen King, let's say, that keeps you reading, that keeps you seeing his movies? Why do you go back to be scared?

Jeremy Dauber: Well, I think those are two really important questions, and King really combines them both. The first, I think, is that what King did, and if you look at the history of American horror, this was not as usual as we'd think now, because we're in a world that Stephen King made, is that you have really ordinary people like you and me who are put into confrontation with these kind of classic horror stories. Dracula is- he's a count and he handles in England. Frankenstein is in a big castle somewhere, right?

But Stephen King's people are like ordinary people who consume the same things that we do. They're consumers like us, they have jobs like us, and then they meet up with vampires. It's that conjunction that makes him feel so very much American, as well as some of his very traditional American values. He's a firm rib rock Methodist growing up, and those kind of virtues in some ways stand his characters in good stead. Except, of course, when they don't.

Alison Stewart: In the book, you separate horror into two categories. The fear of something supernatural, and the other is the monster next door. What falls under the fear of supernatural, and why does the supernatural scare us?

Jeremy Dauber: Yes. I think that the supernatural is a stand in for this big bucket of fear that we have, as you say, one of these. The things that are out there that are much larger and grander than we can possibly control, and that we're sort of helpless in their destiny. Then a lot of times throughout history, and in American history as well, that could be God, right? Certainly at the beginning. But it doesn't have to be. It can also be the idea, and this was very common in the post war period up to now, that you look up and all of a sudden the atomic missiles are flying and there's nothing that you can do about it, or climate change. These big, grand things. Fictional horror helps us work through our fears about that sometimes in ways that are much more controllable. That you can, close the book or finish watching the movie and have some catharsis at least.

Alison Stewart: The same for monster next door?

Jeremy Dauber: Well, the monster next door is a different loss of control, where we really do think we know what's going on. We think that we understand our loved ones or we understand our neighbors, and we know what's happening, but all of a sudden we discover that it's not what- these people are not what we thought at all. Sometimes, maybe that's real, but a lot of times that's a fear that we have that can be preyed on in order to create monstrous outcomes sometimes.

Alison Stewart: We're talking with Jeremy Dauber. The name of his book is American Scary: A History of Horror, from Salem to Stephen King and Beyond. Let's take some calls. Let's talk to Patrice from Manhattan. Hi, Patrice.

Patrice: Hi. Hello?

Alison Stewart: Hi. Yeah, you're on the air.

Patrice: Hi. I first read Stephen King in my early 20s, and I read almost every one of his books, but the scariest thing I ever read or experienced in my life was reading I Am Legend. Specifically, some people don't know that that's a series of stories in that book. I highly recommend it because it's got the highest freaky factor of anything, and that's what scares me when. When it's something I've never wrapped my head around and it's presented to me. There's a story in there about this freaky little idol guy with this woman, and it's just spine-tingling. That's what I like about Stephen King as well. When I first read It, I never have seen that movie. I'm talking about the book. But when I conjured that floating clown head, just kept my spine tingling for minutes and minutes and minutes because I had never wrapped my head around such an idea. That's what scares me. I call it the freaky factor.

Alison Stewart: I love that. Freaky little idol. You got me, Patrice. Let's talk to, Jesse. Hi, Jesse. Thanks for calling All Of It.

Jesse: Hi. Thanks for having me. I told the screener that when I was really little, I grew up in the '80s, and my parents forbade me from watching the slasher- Nightmare on Elm Street, in particular. But I went. I was about like eight or so, maybe a little older. I saw it at a friend's house and it gave me nightmares for days. My parents were upset. But now, as I'm an adult, I love watching horror movies for their uniqueness and their interesting takes. I'm a photographer, so like different camera angles or crazy ideas. In particular, Troma movies. I love those. It is very interesting how I went from being scared to being- laughing and really engaging with them.

Alison Stewart: Jesse, thank you so much for calling. That's an interesting point, Jeremy, when people go from being scared to being fascinated by horror.

Jeremy Dauber: Yes, I know. I think absolutely, and I think what we were just talking about really is important in two different ways. The first is that, these are works that show a certain technique. That technique in part is how to scare us. But as we et more detached, when you asked eight-year-old Jeremy what was the most frightening thing in the world, it's like that kid who was at the top of the show, Vampires. These are terrifying, right? But as you get older, you say, these are works of art that I can also think about how they work and really admire them for that as well. That adds both a quality of appreciation, but also of detachment.

The other thing that he's saying, which I think is absolutely right as well, is that horror and comedy have really a lot in common. I've written about both of them in different books, but they both elicit involuntary reactions from you. Laugh, scream, sometimes they're all combined. A lot of great work has been done that really blends both of those effects very well. Like the Troma movies that this gentleman just mentioned. Movies like the Toxic Avenger. They have some scares, but they also have laughs as well.

Alison Stewart: Let's talk about the fear of the other. It's built into the foundation of this country, the Puritans. How did their fears and their sensibilities shape our fears and sensibilities?

Jeremy Dauber: Oh, that's a wonderful way of putting it. I think that when you talk about a certain founding of this nation, and it's a certain kind of founding, not the only kind. The Puritans who come are these religious refugees, and they're very, very shaped by a worldview in which the world is a very narrow passage between salvation and damnation. Everything about them is seen through that lens. When you take other kinds of fears of marginalized others, of people next door, people like women who are always a card in the deck of a patriarchal society's fear, people of color, Native Americans, that can be translated into, well, if they are scary to us, they're also scary in a way that involves making a deal with the devil. You have those fears put together, and you get witchcraft and you get the hysteria that leads to Salem.

Alison Stewart: Yes, let's talk about Salem. Countless books have been written about Salem. If you've been to Salem, they fully embrace it currently, the town. How is our fascination with the story surrounding the witch trials of Salem transformed over the years?

Jeremy Dauber: I think that Salem- and as you say, this has been a preoccupation, the Salem story. Not just now, but all through American history. People come back to it and come back to it and come back to it. I think because not only is it a story about a particular set of fears, but the way that fear can get out of control, and it can explode, and it can turn into a hysteria that overcomes. That's why people as various as Arthur Miller and Nathaniel Hawthorne can both go back and look at this and say, you know what? This capacity to do that is very much part of our American past and our American present and can lead to all sorts of very unsavory outcomes indeed.

Alison Stewart: What makes the Salem witch trials terrifying today?

Jeremy Dauber: Well, I think that there are two different things that come to mind right away. The first of them is that those witchcraft trials, in certain ways, were also an indictment about women's authority, power, and agency. To say that in the world that we live in now, the question of women's ability, and women's power, women's agency, women's autonomy, bodily and otherwise, isn't very much something that people are thinking about would be, obviously, to a misreading of the current situation. There's absolutely that thing that's still very, very continuous.

The other, I think, is the way in which you can say, what is the way in which a community governs the way that people should think and should live? In the Salem case, that was a theocratic government that really God wants a certain kind of way, but there are all sorts of other ways to say, we're going to be in charge. The fear of that, and the fear of that getting out of control, I think is also very present.

Alison Stewart: Let's talk to Annie, who's calling in from Pleasantville. Hi, Annie. Thank you for calling All Of It on Halloween.

Annie: Thank you guys so much for having the spooky conversation. I love it. First of all, I am terrified. I'm guessing I'm going to be terrified for the next 16 days regardless of Halloween or not. But just wanted to thank you for the conversation and also to say the first thing that really scared me, I read- I'm a huge Stephen King fan. Read everything he's ever written. The first thing that actually really scared me, I think I was in third grade when I read The Shining. Please don't judge my parents. We had an open- you can read and watch whatever you want. The thing that really got to me is when your own perception of reality or if you're reading it, through the narrator or- is in conflict with the reality around them. That's what really scared me in The Shining, that schism between what was being perceived by the narrator whose eyes we're reading through versus what's actually happening. That's how I feel like things are right now.

Alison Stewart: We appreciate you, Annie. Thank you so much for calling in. Hang tight. We are talking about things that are scary. The book is called American Scary: A History of Horror, from Salem to Stephen King and Beyond. It's by Jeremy Dauber. Listeners, we want to talk about our culture's fascination with unsettling thoughts and things that go bump in the night. What are some of your favorite scary stories or books? How did you become interested in the genre? Do you remember the first horror novel that you read? Our number is 212-433-9692. 212-433-WYNC. We'll have more of your calls and more with Jeremy Dauber after a quick break. This is All Of It.

[music]

Alison Stewart: This is All Of It on WNYC. I'm Alison Stewart. My guest is Jeremy Dauber. He is a professor of Jewish Literature and American Studies at Columbia University. He's written a book called American Scary: A History of Horror, from Salem to Stephen King and Beyond. Let's talk about Edgar Allan Poe. We know that Poe is big in horror, but he decided to turn to long form after starting his career as a writer of short stories. Why is that?

Jeremy Dauber: Well, I think that Poe was someone who really tried himself out in all of these different kinds of venues, different kinds of forms. Right after his death, he was as best known as a poet. He wrote that nevermore, he wrote The Raven. He tried this novel form, but I think he found that it really didn't work for him ultimately, as this one novel, like you said. For Poe, horror really was about crafting a work that would lead to a single sensation, a really powerful punch, and the novel form really wasn't sort of great to do that. You can't kind of build everything to one individual sensation.

That said, he really felt that the novel that he wrote, The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym, was going to be in tune with these modernizing times. It's a novel of naval exploration, and in the 1830s, this is the hot idea of what America can be. Going out, exploring, expanding. Poe thinking quite reasonably for a horror writer, well, who knows what you're going to find when you go out there.

Alison Stewart: Someone wrote Edgar Allan Poe's The Cask of Amontillado, which I read as a kid in seventh grade, scared me to death. As for movies, my favorite one was Them. Yikes. Hitchcock's The Birds. Fear it might really happen. Big shout out to Kolchack: The Night Stalker. Let us talk to Michael. Hi, Michael. Thanks for calling All Of It.

Michael: Hey, good afternoon. Thank you for the segment. Love it. I just want to say The Ring is a movie that really terrified me as a kid. Something about a person or a thing coming out of a TV really stuck with me for a long time. Additionally, I have to agree with the other caller about The Shining, but particularly the music that is used in The Shining makes it 10 times more disturbing in my opinion.

Alison Stewart: Michael, thanks for the call. Let's talk to Don. Hi, Don. Thanks for calling All Of It.

Don: Hey. Hey, how are you doing?

Alison Stewart: Doing okay.

Don: All right. I was very impressed by one thing your guest just said a little earlier, which was that we're now living in a world that Stephen King created, which is a really fascinating way and I think probably very apt way of putting it. I appreciate that. I first read Stephen King when I was 12, when Carrie came out 50 years ago. I'm actually attending an event at Symphony Space week after next to celebrate his 50 years. The funny thing for me was I loved the book, I think the movie is just Class A, horror pop film, one of the best ever made, but the book didn't really scare me and neither did the film. The film that really scared me [unintelligible 00:18:50] The Exorcist terrified me. I saw that also when I was a kid. The book was even more frightening. Then, of course, Rosemary's Baby is the other one that I think is just the most classic film in the horror genre.

Alison Stewart: That one got me too. I am with you on both of those things. Thanks for the call. Let's get Evan in one more time. Hey, Evan, real quick, what scares you?

Evan: I saw Alien when I was very young, like 6 or 7. It has ruined all horror for me in literature, in film. It, to me, is still the scariest film ever made.

Alison Stewart: Thanks a lot, Evan. Jeremy, it's so interesting. People are really, really into this horror conversation.

Jeremy Dauber: They love it. I think that it's great to see how many different experiences people have, how many different movies and how many different books have these impacts on people. They're lifelong and great. I love it.

Alison Stewart: You write about HP Lovecraft. He actually has an entire subgenre named after him, Lovecraftian Horror. What happens in Lovecraftian horror?

Jeremy Dauber: Lovecraft really comes out of this moment near the beginning of the 20th century that says, we're moving away from a classical, religious society, but we still need that kind of cosmic sense. What Lovecraft sort posits, following in a couple of people's footsteps but really making it his own, is what if there are these beings that are infinitely more powerful than us? But they at best are deeply, deeply indifferent to us, and at worst, actively hostile. We are like nothing to them. In fact, so much are we nothing to them, that even a glimpse of the worlds in which they live in will drive us totally mad.

Now, that all seems very promising and great, except for the fact that Lovecraft himself was a vicious racist, and anti-Semite, and misogynist, which is not so great. One of the things that really has been interesting is how do you deal with this incalculably influential figure in the history of horror and work with this incredibly toxic and tainted legacy in his life and work? That's been a very interesting conversation in the horror writing community for many decades now.

Alison Stewart: In the book you write, "By the late 1950s, Shirley Jackson had all been praised as one of the great writers of psychological horror of her generation, most notably for her 1948 New Yorker short story, The Lottery." What was specific about her writing?

Jeremy Dauber: Well, it's a great way of putting it because one of the things that's interesting about The Lottery particularly is how nonspecific it is. You have this story which feels like almost a timeless American folk tale about a lottery. I'm not gonna spoil this 70-year-old story, 80-year-old story for people, but it isn't such a good outcome if you win the lottery, let's just put it that way. Critics interpret this in all sorts of different ways because Jackson's mastery is to make it in a way that it could really be about anything and everything at once.

She's also well known for, perhaps, I think the greatest haunted house novel in American literature. I think even King, who loves Jackson, would consider his The Shining, maybe in the number two slot on this, The Haunting of Hill House. If you haven't read this, listeners, I envy you your first reading of this book. It is really just a masterful novel which is both supernatural and also very, very psychological. Just wonderfully poised between those two polls.

Alison Stewart: Yes, this is a good place to talk to John. Hi, John. Thanks for calling All Of It.

John: Hey. Wow, thank you. What a great conversation. I haven't talked about horror movies in I don't know how many years. I used to be such a big fan, but you mentioned so many great shows, so many things that I've loved over the years, but one of the best horror movies I've ever seen is a Dutch movie called The Vanishing, which nobody really talks about that much because it was remade in America with Jeff Bridges as the bad guy, and it was far too violent for the subject matter. The essence of the story was the quietness of it and the fact that the real evil was just a regular guy in his home who killed people. It was so, so intense and terrifying toward the end when you realize what was going on.

Alison Stewart: Thank you for calling in. Yes, I actually we have a text, Jeremy. It said, "I had a phase in 2020 where I obsessed over the movie Halloween and its sequels. I was quarantining from COVID in idyllic suburban setting, so something about the idea of an unstoppable and unknowable force like Michael Myers arriving to terrorize young people in suburbia really resonated with me." That's really interesting.

Jeremy Dauber: It is really interesting. I think first, that notion of moving horror from the cities into the suburbs, which is really happened in the late '60s and especially in the '70s, which is when the Halloween movie, the first one comes out, really is an interesting shift in how it's reflecting what's going on in America. The other is that, as the texter is saying, that notion of unstoppability. This is not a human like the last caller is talking about, some of these other wonderful horror movies. They called this guy in the movie the Boogeyman. The filmmakers called Michael Myers, the shape. He's something really more than human. That's also really quite terrifying in the way that John Carpenter's movie makes that happen. It's a great, great movie.

Alison Stewart: Let's talk to Colin. Hi, Colin. Thanks for calling All Of It.

Colin: Hey, thanks for having me. I got to tell you, not a big fan of the horror genre, but I would say that the scariest movie I've ever seen I saw when I was a child growing up in the '80s, hiding under my desk from nuclear wars and all that was- well, there was a one-two punch. There was The Day After with Steve Gutenberg, which is a very realistic film about what will happen if there's a nuclear war. Terrified me as a child, probably to this day. Then Threads, which was similar, a British version. I don't think of the same story, but post-nuclear kind of realities. I think that kind of anxiety for me as a young person really defined a lot of my early childhood. Maybe I shouldn't have watched it, but I remember.

Alison Stewart: Thank you for calling. Let's talk to Marina, and then we're going to wrap up shortly. Hi, Marina.

Marina: Hi. Yes, thanks for having me on air. I wanted to share something that was really spooky for me. In my eighth grade English class with Mrs. Kopas in Parsippany, New Jersey, we were reading The Telltale Heart by Edgar Allan Poe. Throughout the reading, we just started hearing a beating heart that got louder and louder and louder as the poem went on, and everyone started like looking at each other and feeling really spooked out. I remember being like, oh my God, is this really happening? Is this in my head? Ms. Kopas was playing a trick on us. She was playing a recording of a beating heart, which I thought was so phenomenal. That was a spooky story.

Alison Stewart: That's an incredible story.

Jeremy Dauber: That's fantastic. That's amazing.

Alison Stewart: As we start to wrap up this segment, I did want to ask you a little bit about film. We have Jordan Peele making great movies. We have classic movies like Nightmare on Elm Street. How do you think the, the horror theme, the horror genre is going to evolve? Everything is scary these days.

Jeremy Dauber: Well, I think that's right. I think two things. First, we're in an entertainment landscape, a platform-based landscape where you have so many different kinds of venues for horror, for visual horror than you ever did before. When you were making movies, you said, well, okay, they're going to have to be in a movie screen. If you're in television, it has to be networking. Now you can have movies that really appeal to so many different kinds of horror fans. You can really let a thousand flowers- a thousand poison flowers perhaps, bloom. It's really just wonderful in that respect.

The other thing though is that it is, as we're saying, going to reflect certain kind of conditions. One of the callers talked about how we don't know whether things are real or not sometimes in some of the movies. It does seem to me that that sense of we live our lives online, online is becoming increasingly hard with AI and virtual stuff to tell what's real, what's not. I think that's going to be a very fertile ground for horror and fear. That perceptual play that horror's so good at in the months and years ahead.

Alison Stewart: Thanks to all of our callers for calling. The name of the book is American Scary: A History of Horror, from Salem to Stephen King and Beyond. Jeremy Dauber, thank you so much for joining us.

Jeremy Dauber: Thank you so much for having me. What a wonderful conversation. Thank you so much.

[00:28:05] [END OF AUDIO]