Videos of ICE Violence Are Plentiful. Accountability.… Not So Much.

Title: Videos of ICE Violence Are Plentiful. Accountability… Not So Much.

[music]

James O'Keefe: These people will kill you. I've never quite experienced-- I guess I would call it communism, up close.

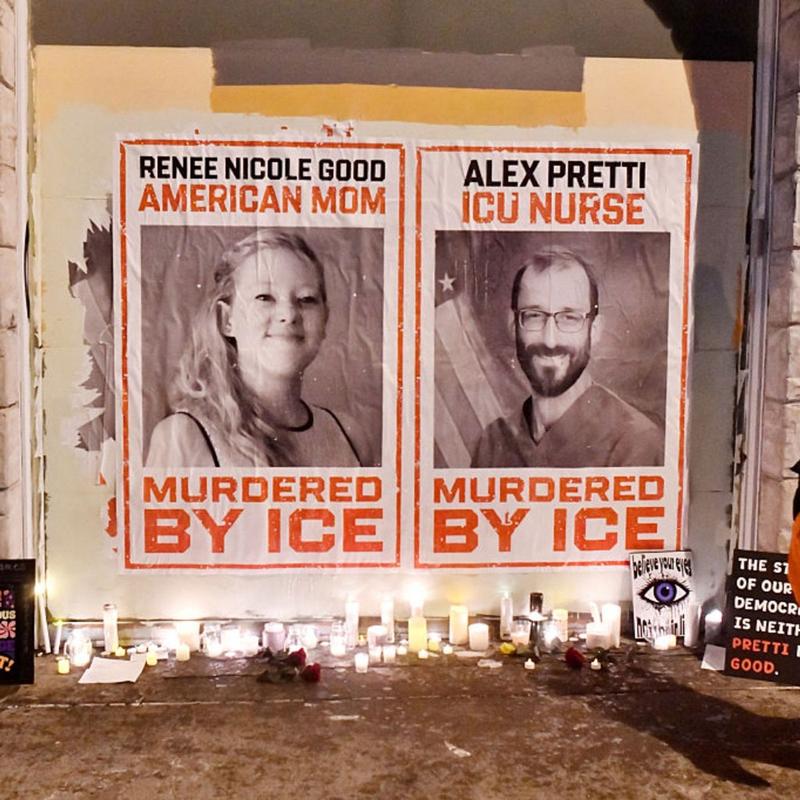

Brooke Gladstone: In Minneapolis, right-wing content creators agitate for tape to change the narrative after the murder of Alex Pretti by federal agents. From WNYC, in New York, I'm Brooke Gladstone.

Micah Loewinger: I'm Micah Loewinger. Also on this week's show, how the political right want us to ignore the inherent Americanness of the protests against ICE.

Radley Balko: I don't think it's unfair to question whether they would be calling Patrick Henry or Sam Adams domestic terrorists if they had been alive at the time.

Brooke Gladstone: Plus, in an era of lightning-fast news and information, the old ways aren't cutting it anymore.

Eliot Higgins: When institutions come along with their lies, the public have already seen for themselves the truth.

Micah Loewinger: It's all coming up after this.

[music]

Micah Loewinger: From WNYC, in New York, this is On the Media. I'm Micah Loewinger.

Brooke Gladstone: I'm Brooke Gladstone.

News clip: The second person has been shot and killed at the hands of ICE agents in Minneapolis.

News clip: The victim has been identified as 37-year-old Alex Pretti, an ICU nurse and US veteran, was shot--

News clip: We heard Stephen Miller go to social media almost immediately. He referred to Pretti as "a domestic terrorist," also "a would-be assassin."

Kristi Noem: The officers attempted to disarm this individual, but the armed suspect reacted violently.

Brooke Gladstone: Department of Homeland Security Secretary, Kristi Noem.

Kristi Noem: Fearing for his life and for the lives of his fellow officers around him, an agent fired defensive shots.

Brooke Gladstone: This time, the Fed's narrative didn't take.

News clip: Eyewitness videos of the fatal shooting of Alex Pretti don't match the Trump administration's version of events.

Micah Loewinger: The shooter was standing behind Pretti and not under direct threat, contradicting statements from Homeland Security officials that he fired defensive shots.

Brooke Gladstone: Within two days, the Trump administration slightly changed its tune, at least briefly.

News clip: Two border agents who fired their guns in the shooting that killed Alex Pretti in Minnesota are now on administrative leave.

News clip: Greg Bovino has now been demoted from his role as border patrol commander at large.

Brooke Gladstone: But you know--

President Trump: He says, "We'll do whatever we can to keep our country safe."

Reporter: You're pulling back?

President Trump: No, no, not at all.

Brooke Gladstone: No, he's not pulling back. People are still being plucked from the streets, and filling those streets is a new influx of right-wing content creators who want to wrest the narrative back, among them, Cam Higby, who's been riling protesters to make videos for his hundreds of thousands of followers. On that same day that Pretti was killed, Higby took to X with a viral post viewed 23 million times. "I have infiltrated organizational Signal groups all around Minneapolis with the sole intention of tracking down federal agents and impeding/assaulting/and obstructing them. Buckle up, all will be revealed."

Brandy Zadrozny: I think he just joined a Signal chat. It's not hard to join a Signal chat.

Brooke Gladstone: Brandy Zadrozny is a senior enterprise reporter for MS NOW.

Brandy Zadrozny: Local activists have shared it to help organize. That has been widely covered in the media, but he joined one, posted a screenshot of it to his 300,000 followers, and says, "Here is where all the planning goes on," for what he labeled "domestic terrorism." The document that you mentioned, this planning document for domestic terrorism, said, "Best practices for observation." In that document, it said very specifically, "We are witnesses, not warriors." It talked about how many bleeps to use on your whistle to alert others in the area for different scenarios.

Brooke Gladstone: How did the right-wing media respond to the post?

Brandy Zadrozny: They ate it up. It was viewed millions of times in Signalgate, it trended on X, and then on Monday, Kash Patel, director of the FBI, went on right-wing podcaster Benny Johnson's program and said--

Kash Patel: We immediately opened up that investigation because that sort of Signal chat being coordinated with individuals, not just locally in Minnesota, but maybe even around the country, if that leads to a break in the federal statute, then we are going to arrest people."

Brandy Zadrozny: Kash Patel and AG Pam Bondi are under immense pressure at this moment to get some results for this war on Antifa, the violent left, that the president started waging over the summer. On September 25, Trump issued this national security presidential memorandum called Countering Domestic Terrorism and Organized Political Violence. It just listed a ton of vague bad guys that President Trump was calling on the FBI to work with local officials to crack down on. Now it is up to Kash Patel to show some results. Benny Johnson really cornered him at that moment, and so he said he's opening an investigation.

Now, domestic terrorism is not a crime, but it does, with this memo, give the FBI license to go and investigate people who are under this domestic terrorism umbrella to try to find crimes.

Brooke Gladstone: You said Kash Patel and Pam Bondi were under a lot of pressure from the Trump administration, but you could say the Trump administration may be under some pressure, too. People saying, "You've been talking about Antifa. Where is it? You haven't arrested anybody." Kind of like, "Where's the Epstein files?"

Brandy Zadrozny: 100%. This is a monster of their own making. In September, when we had that memo come out, two weeks later they called about a dozen of these creators. A lot of these creators that we see in Minnesota right now were at the same table with Donald Trump at this round table, and they all went around basically saying, "Mr. President, finally, someone's doing something about the radical left that we've been documenting for so long. You are right, and our videos can help prove it." Then Trump, in response, said, "Wonderful. Please give all of the stuff that you've collected to Pam Bondi and to Kash Patel."

It's very clear, everybody's operating quite in the open at this point.

Brooke Gladstone: They're operating in the open, but, and maybe we ought to be used to this by now. I mean, some of the things they say are just nuts. Right-wing conspiracist and influencer, Mike Cernovich, of Pizzagate fame, took to X on Sunday calling for the whistles that anti-ICE protesters use to be considered violent weapons. He posted, "High IQ people don't respond well to shrill noises, from smoke alarms to those hearing loss-causing machines that terrorists use against ICE. These things should be considered a violent weapon. They damage hearing for life."

Brandy Zadrozny: It's very stupid. It really is. The thing is, is that this stupidity has always been popular on the far right, at least. You're right, Cernovich was one of the influencers who gave us Pizzagate.

Brooke Gladstone: Caused one person to go into a DC pizza parlor and fire his gun as he was in pursuit of a pedophile ring run by the Clintons.

Brandy Zadrozny: That's right. While all of these folks are blowing up things that aren't real, whistles are now weapons. For example, let's just talk about one of the videos Cam Higby posted, where he was in a car with another creator and people were banging on the windows.

Cam Higby: Get out of the way. Get out of the way.

Brandy Zadrozny: It looked kind of scary, I'm not going to lie, and then they had to peel away. The whole video showed one of the other creators, Nick Sortor, had gotten in a little altercation during the protests a couple of minutes before that, where he grabbed something out of her hand, he tried to pull her mask off, a fight ensued, and then they ran away. That is all very important. At the end of the day, okay, he had to run away.

At the same time we're seeing these videos and these claims being used to say, "These are terrorists," people on the streets of Minneapolis are literally being terrorized. Those videos, taken by bystanders, and mainstream media, and observers, are circulating so widely that I think it's very, very hard for the far right to find a foothold this time. It's lost a little bit of the sauce, I think.

Brooke Gladstone: Yet you still have these two warring narratives battling it out for public attention. The first one, that's all the footage taken by the protesters and the bystanders themselves.

Brandy Zadrozny: That reality is what seems clearly a city under siege. We have seen in the last few weeks, citizens and immigrants alike pulled from their cars violently, pulled from outside of schools. We've seen the videos of the federal government responding to neighbors who say, "Not in my neighborhood. Go away," with violent force, and we're getting to watch it from 10 different vantage points. That narrative is being stacked up online against a totally different one, in which, "The federal government is here to save you, and these bad terrorists are not letting them."

Brooke Gladstone: That's the narrative that's being shaped by maybe a dozen content creators who go from protest to protest and always find the same story, the violent left, and the people organizing against the ICE presence as people who don't really have skin in the game, not as neighbors helping neighbors.

Brandy Zadrozny: The folks making this claim are not from Minneapolis, almost always paid by right-wing political organizations to come to Minneapolis.

Brooke Gladstone: Talk about paid agitators.

Brandy Zadrozny: Absolutely. They come in and agitate, and then they take this video, hold it up to the world and to the federal government. In some cases, Nick Sortor and other creators say that they're in direct contact with Pam Bondi, and say, "This is the proof that you were looking for. Go do something." They're constantly calling for Trump to invoke the Insurrection Act. These are agitators, these are political operatives, but they wear the mask of journalism.

Brooke Gladstone: This week, James O'Keefe, famous for his stings, he told Megyn Kelly on her show that he'd been chased out of a Minneapolis suburb.

James O'Keefe: These people will kill you. I've never quite experienced-- I guess I would call it communism, up close.

Brandy Zadrozny: He has been at this game a long time, and he has some real wins in terms of shaping the narrative, but he has a lot of losses too. This one was not his best work, I will say that. He released a video where he said he had gone undercover. He had also infiltrated these super-secret Signal groups, which are, again, pretty easy to enter. He had this 30-minute video.

Brooke Gladstone: 30 minutes?

Brandy Zadrozny: It's so long. He says he went undercover as a man with a girlfriend who is a special needs teacher. That was his fake story. He found in his investigation evidence of the following: some dude smoking weed, something nefarious about people saying, "Thank you, neighbor."

Brooke Gladstone: Communism.

Brandy Zadrozny: It was fine. The big event from this video was when he had gotten out at one of the neighborhoods where there was protest activity. He started walking around, and some ladies said, "Wear your press credentials." He has a new group called O'Keefe Media Group, OMG, and they said, "That's not a real thing. You're not real press. Get out of here," and he said, "No." He refused to leave. They said, "We don't want you here," and people started circling him, basically, saying, "Shame, shame, shame, shame."

Crowd: Shame, shame, shame, shame, shame, shame--

Brandy Zadrozny: Then he turned to go, and then someone threw something at him, it hit the back of his jacket. It looked like a highlighter. I couldn't really tell what it was. They get in the car and drive away, like, "Get in, get in. Let's go." Someone throws a water bottle at their car, and then he says--

James O'Keefe: They threw a frozen-

Speaker 3: Ice brick.

James O'Keefe: -ice brick at the car.

Brandy Zadrozny: It's too much. It's too much. When juxtaposed with the scenes of real violence in Minnesota, it's unbelievable that they're doing it, actually.

Brooke Gladstone: It's going to be harder and harder for these people because all the tape is out there now. That is certainly what made the Pretti as an assassin claim so short-lifed because they could see he was protecting a woman who was on the ground getting tear gassed in the face, and then pulled away, disarmed, thrown on the ground again. You saw what you saw. What about the video that came out on Wednesday?

Footage of a previous confrontation between Pretti and ICE agents, 11 days before he was shot and killed, it shows him yelling at ICE agents and kicking out the taillight of one of their cars, other agents grabbing Pretty and shoving him to the ground. It's not clear what preceded the events in that video, but how are the right-wing media interpreting it, and how should we interpret it?

Brandy Zadrozny: It seems like it was a volatile moment on the street between ICE and Pretti. I'm not a cop, but I think kicking out the taillight of a car is probably a crime. They probably could have arrested him, and taken him to jail and charged him with something for. That is more information for more of a story about Pretti to me. What that is not, and what the right-wing creators that I'm talking about seem to want to frame it as, is a change in the story of what happened on the day Pretti was killed, that that somehow justifies the other thing that happened.

Brooke Gladstone: The taillight?

Brandy Zadrozny: That the taillight video, they say, "See, he was a domestic terrorist," and therefore, if you follow it to its natural conclusions, what is it, "He deserved what he got."

Brooke Gladstone: There has been much reporting about Border Patrol Officer Gregory Bovino being removed from his post as commander at large this week. Polling from the AP shows that the approval of ICE keeps dropping. Now, 39% of Americans approve of Trump's immigration policies, down from 41% earlier this month. These content creators, they don't seem to be able to break through.

Brandy Zadrozny: I think it's two things. The story of Minneapolis first. The way that they have fought back has really got a lot of the country on their side. The second thing, and part of why that is, is power of observation. Even when I first heard about the patrols going around and observing, I think that there was a part of me that was like, "Okay. That's cool." I had no idea the power of those videos and the power that it would have over the narrative.

Brooke Gladstone: Do you think that there were lessons learned from the George Floyd tragedy?

Brandy Zadrozny: In Minneapolis, 100%. Trump made a really big mistake coming to Minneapolis. People are organized there around social justice movements. They care about their neighbors. They've been through so much already, from Black Lives Matter movements starting in Minneapolis, and then don't forget, the demonization of Minneapolis because of those protests. There's still this narrative that the whole town burned down when you have the federal government coming in and seeking to start another false narrative. I think we saw that they said, "No way."

Brooke Gladstone: The AP reported that Trump has "shifted toward a more conciliatory approach." A New York Times story on Thursday quotes "Trump's border czar Tom Homan," who took over in Minnesota, saying that they're working on a plan to draw down the number of agents there. Do you believe that this is a genuine Trump pivot, or does Trump never really pivot, he just pirouettes?

Brandy Zadrozny: I saw Tom Homan speak before the National Conservatism Conference in September, and he said, "If you like what we're doing now, just you wait." It made me curdle for the glee that he seemed to emit. I'm very skeptical that Tom Homan is going to be the person that somehow institutes a more progressive lens with regard to enforcement. I think we should be careful with that framing in our expectations, and I think that we should be focused on where they're headed next.

Brooke Gladstone: Do you have any indication, any guess?

Brandy Zadrozny: If I had to put money on it, Springfield, Ohio. Large Haitian community who has lost protected refugee status as of early February, maybe the 4th. Springfield is not Minneapolis. Whether the lessons from Minneapolis will move over to Springfield or a place like Springfield, TBD.

Brooke Gladstone: Brandy, thank you so much.

Brandy Zadrozny: I appreciate it.

Brooke Gladstone: Brandy Zadrozny is a senior enterprise reporter for MS NOW, focusing on far-right extremism, online misinformation, and conspiracy theories.

[music]

Micah Loewinger: Coming up, an American city occupied by outside troops, civilians shot dead in the streets. Sound familiar?

Brooke Gladstone: This is On the Media.

[music]

Brooke Gladstone: This is On the Media, I'm Brooke Gladstone.

Micah Loewinger: I'm Micah Loewinger. You'd be forgiven for thinking that the killing of two American citizens by federal immigration officers might force the administration to slow its roll, but the siege of the Twin Cities continues. Just after Renée Good was shot, New York Times columnist, Jamelle Bouie, observed that "not since the British occupation of Boston, on the eve of the Revolutionary War, has an American city experienced anything like the blockade of Minneapolis and its surrounding areas by the federal government."

He's referring, of course, to the Boston Massacre, the evening of March 5th, 1770, when British troops shot and killed five colonists. Pieces in The Boston Globe and other outlets have since drawn the same analogy.

Ken Burns: For 17 months, Boston was an occupied city. The rattle of drums awakened residents every morning. Passersby were routinely stopped and searched.

Micah Loewinger: Director Ken Burns chronicled the now familiar conditions that preceded the massacre in his 2025 documentary series titled The American Revolution.

Ken Burns: From London, Benjamin Franklin was concerned.

Benjamin Franklin: Some indiscretion on the part of Boston's warmer people, or of the soldiery, may occasion a tumult. If blood is once drawn, there is no foreseeing how far the mischief may spread."

Micah Loewinger: Radley Balko is author of Rise of the Warrior Cop: The Militarization of America's Police Forces. This week, writing in his Substack, The Watch, he dove into the striking similarities in recent reports from Minneapolis and the dispatches from an anti-monarchy newspaper covering Colonial Boston.

Radley Balko: I found this archive called A Journal of the Times, a bunch of old copies of this newspaper from the 1760s and 1770s. When you read through these accounts of these daily interactions, squabbles, confrontations between soldiers and colonists, it reads like an old-timey social media feed. It's a little bit gossipy, it's written in a one-sided manner, but it was also consistent with contemporaneous accounts of what was happening in the city at the time.

Micah Loewinger: It was a pro-patriot, anti-monarchy paper.

Radley Balko: Yes, absolutely. It was definitely sympathetic to the colonists and hostile to the British troops. Over the course of history, we see the same types of abuses of power repeat themselves, and we see the same types of reaction to those abuses from the people on the receiving end of them.

Micah Loewinger: Do you mind just reading through some of the ones that stuck out to you?

Radley Balko: Here's an account that's particularly straight and to the point. Gentlemen and ladies coming into town in their carriages were threatened by the guards to have their brains blown out unless they stopped. It immediately reminded me of, after the killing of Renée Good--

Immigration Officer 1: Get out of the car. Get out of the [beep] car. Get out of the car.

Radley Balko: We saw these videos and witness accounts of immigration officers trying to intimidate other ICE watchers to back off.

Immigration Officer 2: You're not going to like the outcome.

ICE Watcher: Go home to your children. It's Sunday.Let people go to church.

Immigration Officer 2: You did not learn from what just happened?

Radley Balko: Here's one about how the people responsible for these policies know how unpopular they are, and protect themselves accordingly. From the old paper, it says, "This night, the sheriff procured guards of soldiers to be placed at his house for his protection, a measure that must render him still the more ridiculous in the eyes of the people." That reminded me of the fact that Stephen Miller along with Kristi Noem and I guess Marco Rubio, have all moved out of their homes and are now living on military bases. They've deliberately put themselves away from the people, I would argue, knowing how unpopular their policies are.

Micah Loewinger: You also observed similarities between great shows of force, like a kind of military exhibitionism that was on display both in Boston and now in Minneapolis.

Radley Balko: Yes, that was the next one, actually, I was going to read. It says, "There was a general appearance of the troops in the Common, who went through their firings, evolutions, in a manner pleasing to the general. The glitter of the arms and bayonets, and this hostile appearance of troops in a time of profound peace, made most of the spectators very serious, and reminded me of what a late traveler related in his own account from Turkey."

Here, the author in the 1760s is talking about what he heard about somebody who had visited Turkey. He says, "There was present a day when the Grand Signior was passing from his palace to the mosque, and observing the Janissaries stood without arms, with their hands across, and only bowed as the Sultan passed. He was led thereby to ask a captain of those guards why they had no arms, and he said, 'Thou infidel, arms are for our enemies. We govern our subjects with the law.'"

That's one of the regular themes we see in these accounts from Boston is these shows of force just to intimidate and put the fear into people. Gregory Bovino in his intimidating attire that some have said evokes Nazi Germany. In Minneapolis, he would show up with his caravan surrounded by armed bodyguards, and just walk through neighborhoods and yell at people.

Speaker 4: The forces of Greg Bovino are out. A veteran of the war in Afghanistan walked by me and said, "He's driving around town like an Afghan warlord." He's never seen anything like it.

Micah Loewinger: You mentioned Stephen Miller. Writing in The New York Times, Jamelle Bouie drew a connection between the language that Miller used after the recent killing of Pretti and British occupying leaders in the colonial era. Bowie wrote, "Stephen Miller has called protesters violent agitators, and accused Minnesota state officials of fomenting an insurgency against the federal government. In the same way, the British general who oversaw the British occupation, Thomas Gage, described Bostonians as mutinous desperados who were guilty of "sedition."

Radley Balko: I think this really lays bare the disconnect between supporters of President Trump claiming to be the inheritors of the traditions and ideas of the founders, and supporting the occupations of these cities, which bear such a striking resemblance to what happened in Boston. I don't think it's unfair to question whether they would be calling Patrick Henry or Sam Adams domestic terrorists, if they had been alive at the time, and not the patriots that they seem to think they were today.

Micah Loewinger: Let's talk about the actual night of the massacre. Here's a clip from the Ken Burns' Revolutionary War series.

Narrator 1: On the evening of March 5th, 1770, there were tussles between Bostonians and British soldiers all across the city. At the Royal Customs House, a crowd of young men surrounded a lone sentry and pelted him with snowballs and chunks of ice. Convinced a citywide uprising was underway, Captain Thomas Preston raced several armed grenadiers to the scene. More snowballs, and rocks, and oyster shells greeted them. They fixed bayonets.

Narrator 2: Somebody starts ringing the church bells, which in Boston is a sign for fire. Some people are bringing buckets to be part of a bucket brigade. Some people are drawn by the noise. It's very hard, in fact, impossible to know what happened, which is that somebody yells, "Fire."

[gun shots]

Micah Loewinger: Immediately after that night, there was a war of narratives. The British called it the Incident on King Street, and claimed that the soldiers had acted in self-defense. We call it a massacre in large part because of an engraving, a piece of propaganda that Paul Revere printed and sold. I think everyone who's listening has probably seen it in their textbooks growing up. It depicted a clear line of soldiers who appear to have been ordered to shoot into the crowd, which is not historically accurate, but was nevertheless very effective in helping shape our memory of the night then and now.

Radley Balko: At this point, historians largely think that the shooting by the soldiers was probably justified, probably genuinely thought that their lives were in danger, but the anger that was being directed at them was also righteous. It was the product of people who were tired of being occupied, who were tired of seeing soldiers march through the streets, who were tired of having their doors kicked in with these general warrants. It was this confrontation that had been slowly building up for years.

That is exactly what we would expect to happen when you put soldiers in the middle of a city. I think if we had not had the video from the killing of Renée Good and Alex Pretti, there would still be competing narratives about what happened.

Micah Loewinger: After the Boston Massacre, there was a legal reckoning. John Adams, who would, of course, go on to become our second president, actually stepped up to defend the British soldiers in court.

Radley Balko: Adams was a fervent patriot, as was Josiah Quincy, the other person who represented the soldiers, and they both saw it as a duty to do so. Now, there may have been some propagandistic value to that, to say, "Here, in Boston, we're going to make sure everyone has due process, even though the Crown doesn't do the same for us," and it was a way of winning people over, but the trials were about as fair as you could expect at the time. I believe of the six soldiers who were tried, all but two were acquitted. The two, they were supposed to get the death penalty, instead they were branded on their thumbs.

That is an important moment because it showed that even in the face of what were perceived to be these infringements on personal liberty and this daily abuse that was happening during this occupation, they were willing to give these soldiers fair trials. Contrast that to what's happening in Minneapolis, where you have an administration that, from day one after these shootings, has declared that these shootings were justified, even righteous.

You had Todd Blanche, the number two person at DOJ, saying that there would be no investigation of Renée Good, and whatever evidence the FBI had already collected at that time would not be shared with state and local officials. As we talk now, it looks like, at least in the case of Alex Pretti, that there's going to be some kind of investigation.

Micah Loewinger: Increasingly, we see Trump depict himself as a monarch. We see a federal government that behaves more broadly as our former oppressors once did to us. I wonder if you think that this is yet another piece of evidence that the behavior of this administration is in some way inherently un-American.

Radley Balko: I think it's important to distinguish between the myths we have about what America is and isn't, and what it actually is or isn't. We call ourselves a country of immigrants, and I think there's a lot of truth to that in the sense that immigrants have built this country and become an important part of our cultural fabric, but we also tend to forget that every single wave of immigration was accompanied by really virulent anti-immigrant fervor and sometimes violence, as we're seeing now.

I do think, as we saw with the popularity of the No Kings protests, where you had people who'd never protested in their lives came out, it bothers us when you have an administration that isn't even trying to live up to those values. When after one of these shootings, when the administration is just openly, and exaggeratedly, and ridiculously lying to you in a really performative way, that's spitting in the face of these ideas that we cherish.

Micah Loewinger: Do you find the historical resonances reassuring or disheartening?

Radley Balko: Both. Reassuring in the sense that there's always some comfort in the idea that we've been here before and we got through it, but if we're going to be comparing this to Boston, there was a lot of bloodshed before things resolved. I've been inspired in this last year after watching all of these institutions buckle, in some cases really embarrass themselves in their effort to appease an administration that is really exerting its power in alarming ways, that the resistance and the stand that we've seen have just come from regular people.

I wrote quite a bit about the surge into Chicago by federal immigration forces. I have friends who have never been political in their life who were organizing teams to go to local schools to escort immigrant kids home so that they wouldn't have to worry about getting stopped and arrested. Chicago is really where we saw the whistle brigades start. I think that character, and it's certainly not uniquely American, of sticking up for your neighbors, looking out for the people around you, that was dominant in Boston.

You see that in these first-hand accounts from the time. It's definitely what we've seen in Chicago, and Los Angeles, and Portland, and Minneapolis. Wherever they go next, I'm confident and hopeful that we'll see it there, too.

Micah Loewinger: Radley, thank you very much.

Radley Balko: Yes, my pleasure. Thanks for having me.

Micah Loewinger: Radley Balko writes a newsletter on Substack called The Watch. He's also the author of Rise of the Warrior Cop: The Militarization of America's Police Forces.

Brooke Gladstone: Coming up, a cure for our collapsing democracy. Not quick or easy, but not impossible either.

Micah Loewinger: This is On the Media.

[music]

Micah Loewinger: This is On the Media, I'm Micah Loewinger.

Brooke Gladstone: I'm Brooke Gladstone. Top government officials thought they could spin a story based on lies about the deaths of Renée Good and Alex Pretti, despite the abundance of evidence to the contrary. This time they haven't, though the Trump team is still trying, still trying. The fact that they think they can points to something we've long observed in Russia, China, and Europe, certainly here, that the obliteration of shared realities leads many to believe that actual truth is inaccessible or irrelevant, and that's when democracies begin to rot.

Eliot Higgins: Disinformation is the catalyst, is the symptom, but it is not the fundamental cause of the problems that we're facing today. They're far deeper.

Brooke Gladstone: Eliot Higgins is the founder of Bellingcat, a global collective of researchers, investigators, and citizen journalists who use open-source information both to break and authenticate news stories in real time. He co-authored a paper in October that lays out why things went so bad and how to reverse the rot. It's called Verification, Deliberation, Accountability: A New Framework for Tackling Epistemic Collapse and Renewing Democracy.

Eliot Higgins: You would have this thing come up saying that, "Oh, people have lost trust in institutions," but what is that trust even based on? That's like going to the doctor and saying the doctor says you're ill because you lack wellness. What I wanted to do is, okay, let's unpick what that trust is really based on. Looking back through various academic work, sociology, philosophy, psychology, particularly in the post-World War I and post-World War II era, where there were real challenges to democracy in the face of authoritarianism, three core functions of democracy became apparent to me.

Brooke Gladstone: You identify these three components as foundational functions of democracy: verification, deliberation, and accountability, hence the VDA framework. Just start with verification.

Eliot Higgins: Verification is the idea that we can come to a shared understanding of what's really happening in the world around us. Traditionally, that's been done by institutions primarily, like the media, the government. They have the resources to be able to do that. In the 20th century, we had this top-down model of information. You would have newspapers deciding who got access to be written about. The guy on the corner holding a sign saying the Earth is flat didn't get put on CNN. That was an environment that had the scarcity of information and an excess of public attention for it.

The problem is now that's been flipped on its head because we've got lots and lots of information and not enough attention as a public to respond to that in that old way. This is where we're starting to have problems, I think, in democracies because, first of all, institutions are still clinging on to the old way of holding power, that they're the ones who have the authority over these processes. In reality, people have lost faith in those institutions for legitimate reasons in many cases, and they seek alternatives in these online spaces, which aren't designed around careful deliberation, and verification, and accountability, they're designed around engagement.

Brooke Gladstone: Right. You say that verification can collapse into hollowness when it becomes more of a performance. Is that when RFK Jr cites made-up studies when Kristi Noem says a protester murdered in Minneapolis was hell-bent on mayhem?

Eliot Higgins: This is the thing, they claim authority, they say we have this information, and it turns out to be untrue. Often, what you see in online communities who support these movements is they'll manufacture evidence, which is a simulation of verification. It's about selecting sources that will already reinforce what you and your group want to believe. If you're not loyal to your in-group, say MAGA, for an example, you will be punished and you will be exiled for that. You can look at people like Marjorie Taylor Greene, for example, because this isn't about having a debate about the facts, it's about the facts being pre-selected to reinforce the conclusions of the group that's currently in power.

Brooke Gladstone: As you said, we used to be in an information-scarce, attention-rich environment, now it's flipped, and that we're trying to figure out the world on a stream of stuff that you say is being delivered to us algorithmically.

Eliot Higgins: Yes. We are now constantly engaged with information that's being served to us by an algorithm that rewards whatever gets attention because platforms want to keep people online. The problem is, certain approaches to information from more populist, conspiratorial, and authoritarian movements where they provide certainty, and a sense of belonging, and a group identity outperform slower forms. That becomes really, really dangerous because it means the very underlying information substrate we exist in, that society works in, leans towards those populist, conspiratorial, and authoritarian outcomes rather than functional democratic outcomes.

Brooke Gladstone: When you talk about the D, deliberation, you say that has also become performative in the countless numbers of government commissions and committees that produce nothing.

Eliot Higgins: When institutions fail to deliver real deliberation, they do this performance of it. You can find online spaces where you can be involved with conversations. You can be an influencer within that. You can be recognized as someone whose opinions matter, but if those become spaces that are pre-selecting the information that's allowed into the community, then that just really becomes about reinforcing the group identity rather than actually challenging information and analyzing it in any real way.

Brooke Gladstone: When they're doing the research, what does that mean?

Eliot Higgins: When people say they're doing research, what they're really doing is seeking stuff that reinforces what they already believe. Anything that contradicts that information can be framed as corrupt in some way. That's a very, very powerful dynamic.

Brooke Gladstone: Now, let's go to accountability. CNN is reporting now that the investigators charged with running the internal customs and border protection probe into the murder of Alex Pretti are getting only limited access to the evidence held by the Department of Homeland Security and the FBI. This seems to be setting the stage for a kabuki accountability, doesn't it?

Eliot Higgins: It's really part of what you often see in more authoritarian systems because by the point they've actually had to be forced into the performance of accountability, shall we say, it's really about punishing people who don't really matter, that can be easily replaced. There's a performance to the public, "Oh, we've done something about this," but the underlying conditions still exist. They're just moving the pieces around the board.

The people who are loyal members of the in-group but have embarrassed the in-group in some way through their failures are punished and replaced, but the people who really hold power within that group, they're protected from any real accountability. I really see this happening a lot in the US at the moment.

Brooke Gladstone: Oh, yes. The public's frustrated. Epstein files, so redacted that they're worthless, not much accountability there. As for political corruption, the fact is a lot of big-time executive office staffers went to prison after Watergate, but look at Trump's crew. Look at January 6th perpetrators. Just look at Trump himself. Accountability is your crucial third pillar. That's when people really get to see that it is so often only performative, and that they have no real voice and no real power, that their role in the democracy is no role at all.

Eliot Higgins: Again, we have alternative solutions when we feel disempowered in that way. We have communities we can find in online spaces that make us feel empowered. Again, many times that's an illusion, it's not real power. It's just being able to find another community on the internet to shout at and abuse.

Brooke Gladstone: Talk to me about the four pillars of disordered doubt.

Eliot Higgins: The first one is doubt the evidence. That's saying, "Oh, that image, that video is unreliable." Something you see a lot now is AI-generated videos being all over the place, according to some people, but only when it contradicts what they're believing. In fact, I've even seen one today. There was a piece of footage that was being shared with Alex Pretti kicking a vehicle.

Brooke Gladstone: A taillight. Yes, that one's real.

Eliot Higgins: Yes, but people are saying immediately, reflexively, "Oh, that's AI-generated," because it made them feel uncomfortable. It happens constantly. We have doubt the source. It's saying that the messenger who's showing it, be they journalists, experts, or institutions, aren't trustworthy in some way. It's like when Trump calls something fake news, that's doubting the source immediately. You then have doubt the process, the actual methods being used to verify information. That's something that can be deployed constantly because it's not really falsifiable.

If you're saying, "Oh, they're a corrupt organization, you can't trust them, and their processes are wrong," then your group is willing to accept that without actually looking at the processes itself. Then, finally, is doubt the claim. It endlessly raises the bar of proof, shifting the goalposts. No matter what evidence you produce, no matter how good the source is, no matter how good the process is, they're saying, oh, you're not 100% sure, or, "What about this bit of information? Have you considered this? If you're not sure about that, then how can you be sure about anything else whatsoever?"

This is used to often not even refute the truth, it's just evaporating it away because it's constantly attacked.

Brooke Gladstone: It's all to Trump's benefit if people believe the truth can't be found.

Eliot Higgins: Exactly. What you also see happening at the moment, for example, is that once it becomes too overwhelming, they say, "We can't comment on it because there's an ongoing investigation," but either the investigation is going to be fixed, or they're going to claim it's been fixed. They're setting themselves up so they can never lose, or rather the other side can never win because they make the truth impossible to actually establish. It's a self-sustaining system of doubt.

Brooke Gladstone: In your paper, you talk about counter-publics, what we'd call protest movements, and how assessing those can give you an angle on the state of a democracy. Counter-publics, like democracies, can also be functional or disordered.

Eliot Higgins: Now, when we're looking at the 20th century counter-publics around voting rights, around civil rights, they affect institutional change that is substantial to a point. That is not to say that all these problems are cured perfectly, but it does shift those institutions in the direction. It makes the public recognize those injustices. When you have a situation where you now have these online spaces where you have the formation of these disordered communities, which are based around conspiracy theories, they feel equally justified in their beliefs as the civil rights movement did.

They feel this is a real issue that needs to be changed. Now, normally they don't have access to institutions or power, but what we've seen, really, over the last 10 years, I would say in particular, is the rise of, first of all, populism. That's very compatible with conspiracy theories. They both distrust institutions. The conspiracy theorists can say, "We're trying to find the truth," and populists are saying, "This is a community that can be part of my coalition."

I think this is how you end up in the US with a MAGA coalition of populists in terms of Trump, but also conspiracy theorists like RFK Jr, Tulsi Gabbard, Kash Patel getting these positions of power because they're bringing a community to that coalition, who will vote for Trump because they believe they can have access to the truth now. As we've seen with the Epstein files, for example, that doesn't always work, and then there becomes these fractures that start forming in those coalitions.

Then, these populist conspiratorial movements start moving towards authoritarianism because you have to start excluding people for being disloyal.

Brooke Gladstone: Let's talk about speed. You suggested that a big reason institutions have failed to sustain democracy is that the mechanisms they once used, like investigative journalism, parliamentary debate, judicial review, protests even, and civic activism, they no longer suffice because bad information outruns the good.

Eliot Higgins: Yes, absolutely. I think the recent shootings in Minnesota are a really good example of why that's important. Immediately within hours of these shootings happening, you're seeing the official institutional response that is saying these people are domestic terrorists, that guns were brandished, that events happened that didn't really happen on the ground, but because we're able to gather all this information, quickly process and verify it, and then get it out.

Brooke Gladstone: Bellingcat was very much in the forefront of that.

Eliot Higgins: What we have at Bellingcat, it's not just our 40 staff members. We have a trained volunteer community of about 100 people constantly collecting videos from these ICE raids. We've got a whole data set of lots and lots of images, photographs that we've verified, we've geolocated them, added metadata to. Above that, we've also got a Discord community of about 35,000 members, who really believe that the truth matters, gathering this information. We're drawing that down, reviewing that very quickly, verifying it, and then getting that out to the public through our social media channels.

That starts informing the discourse that's forming in those public spaces. When institutions come along with their lies, the public have already seen for themselves the truth. That's really, really important. You can't wait a day, two days a week, or however long it is, to get that information out to the public, because the narratives are forming in real time. We need to think about this not as, "At the end of this, what do we do about it?" "Oh, we better get some fact checks out. That'll fix things." No, that doesn't work.

Brooke Gladstone: Because public judgment has already cohered.

Eliot Higgins: Yes, because we also need to think that we are distributors of information. We create information as the public now that competes for attention in the same space as the information institutions are creating. That can be a problem, but I think the work of Bellingcat shows that actually that can be a good thing as well. You need to build the structures for that. You need to get out there training people. Like we're doing a lot of work at the moment with creating university hubs where students can do open-source investigations, and we want to connect those to local communities. I could imagine in the US at the moment, that's something that could be very beneficial in the short, medium, and long term.

Brooke Gladstone: What are the serious interventions we can employ to address the mess we're in?

Eliot Higgins: We need to think to ourselves how we create functional verification, deliberation, and accountability in this moment of democratic crisis. That can involve institutions, but it shouldn't just involve the institutions. We are all interacting in the same environment. The work of Bellingcat over the years has shown-- I was an ordinary member of the public. I was not a journalist, or working for a think tank.

Brooke Gladstone: What were you doing? I want you to tell me that you were a hairdresser or you sold shoes.

Eliot Higgins: I used to actually work for a company that sold ladies lingerie.

Brooke Gladstone: I love you.

Eliot Higgins: I taught myself these techniques. I've taught other people how to do that. Any American and any community can do it. We'd really love to be engaging more in training local news organizations, for example, to do this kind of work because once you start doing that, you are empowering people. I started off, like I said, working for a company that sold lingerie. I am now cited in international court cases against major governments.

Brooke Gladstone: Bellingcat, by being among the first to verify the videos documenting the murder of Alex Pretti, to figuring out who poisoned Alexei Navalny, and so many investigations in between, has the standing to teach verification, but what can you do about deliberation or accountability?

Eliot Higgins: Let's talk about deliberation. Deliberation cannot happen if there's not functional verification in the first place. We teach people the skills to do that verifying, so that then they can become part of the discourse around deliberation. Again our work on Minnesota allowed us to get people talking about that, that it pressured institutions, the government, into reacting into a way that they probably wouldn't have otherwise. That brings about accountability.

Now, sometimes accountability is forcing an authoritarian government to change course in some way. Sometimes it's about getting into courtrooms and finding accountability there. Without that functional layer of verification to begin with, the rest of it doesn't happen.

Brooke Gladstone: Are you asking for populations to become super computer-savvy? If it requires people to have the actual skills to find the truth, I fear we're dead in the water.

Eliot Higgins: I'm not saying every single person has to become an open-source investigator, but education is part of this. We can't just say we're going to have the same primary, secondary, and university education that we've had in the 20th century because that's based around whole ideas of democracy and information systems that are becoming defunct.

Brooke Gladstone: You think it's going to take a generation then? That's a dangerously long period of time.

Eliot Higgins: This is the thing, there's no quick fix to this. There are actions that we can take now to mitigate some of this damage, but we really need to think about how democracies function beyond the 20th century models because we aren't going back there. If we ban all the social media platforms tomorrow, it wouldn't fix the underlying problems. Trust in institutions has to be re-earned, but also we need to recognize that the public can be empowered.

That empowerment shouldn't be something that's scary for institutions, they should see that as an opportunity to almost renegotiate the terms that our democracies have been built on. That might sound like a big, big idea, but another big idea is authoritarianism is camps full of immigrants. That's exactly what's happening now. Maybe we need a big idea to counteract that. Otherwise, we'll see a lot more of it.

[music]

Brooke Gladstone: Eliot Higgins is the founder of Bellingcat. Eliot, thank you very much.

Eliot Higgins: Thank you.

[music]

Micah Loewinger: That's it for this week's show. On the Media is produced by Molly Rosen, Rebecca Clark-Callender, and Candice Wang. Travis Mannon is our video producer.

Brooke Gladstone: Our technical director is Jennifer Munson, with engineering from Jared Paul. Eloise Blondiau is our senior producer, and our executive producer is Katya Rogers. On the Media is produced by WNYC. I'm Brooke Gladstone.

Micah Loewinger: I'm Micah Loewinger.

[music]

Copyright © 2026 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.