The Rise and Fall of Alt-Weeklies, and Backpage.com vs The Feds

( NYPL / New York Public Library )

Katya: Hi. It's me, Katya, EP of On the Media. Over the last couple of weeks, we've been in your ears asking for help to support the show. You've heard from Brooke. You've heard from Micah. Now it's my turn. As the manager of this outfit, I am not going to dress it up for you. I'm going to tell you how it is. If every single one of you, every single one of our listeners, gave $1 to the show right now, we'd have enough to cover the budget for a couple of years, but that's just not a realistic goal. What is a realistic goal is getting the 2% of you who donate up to 3%. It's just 1% difference.

Maybe you're listening to me now, and you're thinking, "Oh, I'll get to it later, or it's just too complicated to make a donation or even someone else will do it." Well, here's what I have to say to you. Don't put it off. Do it now. It's super easy at our website. It's literally one click. Do you expect someone else to pay for your New York Times subscription or your Netflix account? No. Right? It's time to pay for On the Media. We're counting on you guys. Thanks.

News clip: The Village Voice is no more.

News clip: After more than four decades in print, the City Paper is shutting down.

News clip: A weekly connection to Twin Cities culture, now, just a 41-year chapter in its journalistic history.

Micah Loewinger: What happened to the Off the Irreverent alt-weeklies that used to populate newsstands across the country. From WNYC in New York, this is On the Media. I'm Micah Loewinger. On this week's show and Ode to The Village Voice.

Tricia Romano: The Voice was to guide delight from people who cared about what they were covering with such intensity that there were fist fights and brawls inside the paper. That's gone.

Micah Loewinger: Plus, the founder of an infamous chain of alt-weeklies finds himself in hot water over his Craigslist competitor.

Mike Lacey We started in 2004 Backpage, because we knew that the classified business was going away.

News clip: Backpage.com seems to have knowingly allowed women and children to be exploited.

Micah Loewinger: It's all coming up after this.

Micah Loewinger: From WNYC, New York, this is On the Media. Brooke Gladstone is out this week. I'm Micah Loewinger. alternative weeklies. Alt-Weeklies are the type of offbeat fearless publication that once upon a time you could pick up on a street corner in a bar or cafe in cities across the country. Over the course of roughly 60 years, they transformed journalism. Today they're nearly extinct.

News clip: Well, it is the end of an era. This week is your last chance to grab this, the current issue of The Baltimore City Paper.

News clip: The Village Voice is no more. The Pulitzer Prize-winning paper was known for its coverage of politics, music, theater, and the gay community.

News clip: A weekly connection to Twin Cities culture. Now, just a 41-year chapter in its journalistic history.

News clip: Tomorrow's edition of the San Francisco Bay Guardian is going to be the last.

Micah Loewinger: The Boston Phoenix, Urban Tulsa, Philadelphia City Paper, San Francisco Bay Guardian, and Knoxville Mercury have also closed shop. They aren't totally gone. The Association of Alternative News Media lists 101 members, but those that survive must contend with constant mergers, buyouts, and financial precarity. The legacy of Alt-Weeklies, however, lives on in a generation of astounding writers, including, but in no way limited to, Wayne Barrett, Joe Klein, Katherine Boo, Ta-Nehisi Coates, David Carr, Susan Orlean, Jonathan Gold, Colson Whitehead, Ann Powers, Anil Dash, and on and on.

They went after local politicians, championed weirdo artists, and challenged the status quo, including the conventions of journalism and writing. For the next hour, we'll celebrate the guts and glory of a bygone media era. Beginning with a look back at where it all began, in Greenwich Village. In 1955, Norman Mailer took the money he'd earned from his bestseller, The Naked and the Dead, and together with Dan Wolf, a psychologist and publisher, Ed Fancher founded The Village Voice.

Tricia Romano: They wanted to create a paper that reflected the Greenwich Village that they knew and loved, Beatnik culture and jazz and writers like James Baldwin.

Micah Loewinger: Tricia Romano worked at The Voice in the '90s and 2000s. She's the author of a new oral history titled The Freaks Came Out to Write the Definitive History of The Village Voice, the Radical Paper that Changed American Culture. She explains that at the outset, editor Dan Wolf had a preference for hiring amateurs. As he put it, "It was a philosophical position. We wanted to jam the gears of creeping automatism."

Tricia Romano: Journalism at that time was very much who, what, where, why, when. It's almost like constructing a puzzle piece rather than it is writing lyrically in any way. He and Norman Mailer also leaned towards writers writing, and they knew that if you loved something and you were passionate about a subject, you were going to bring that passion to The Voice in a way that an objective newspaper reporter really wasn't even allowed to.

Micah Loewinger: Give me a couple examples of people who fit in at The Village Voice helped define its style, but probably wouldn't have gotten hired at one of its competitors.

Tricia Romano: You've got Jules Feiffer, who was the Pulitzer-winning cartoonist who wrote the satirical, very adult comics about relationships between men and women called Sick, Sick Sick. He got paid nothing for many years. Then Jonas Mekas, the Lithuanian refugee, who was an avant-garde filmmaker and director and hosted loft parties and showed Andy Warhol films. He walked in one day, he says, "How come you don't have any columns on cinema?" He said, "I don't know. Why don't you do it?" He started doing that.

Then you had Richard Goldstein that comes along later, and he is the first rock critic by many people's calculations. He is actually one of the few people who actually did go to journalism school, which he tried to hide. [laughs]

Micah Loewinger: Because they'd see him like a square?

Tricia Romano: Yes. Well, he was the weirdo at his journalism school. He had long hair, and he tells a joke how he messed with the instructors. He would put a sugar cube on his desk.

Micah Loewinger: Because they would think it was acid.

Tricia Romano: Yes. [laughs] He was embedded in the early rock scene and hanging out with Warhol in the Velvet Underground and all of those people. He quickly became very well known for this, because that music was just starting to explode.

Micah Loewinger: From December 1962 to March 1963, seven major daily newspapers in New York went on strike.

News Reporter: No news is bad news to eight million New Yorkers when strikes closed down their daily papers.

Micah Loewinger: The Voice didn't, and since it was available on newsstands, it stood out to New Yorkers outside of Greenwich Village for the first time leading to a spike in its circulation from about 28,000 to 35,000.

Tricia Romano: That audience discovers, "Oh, they're covering stuff that I go to or I'd like to go to and I don't read about it anywhere else." We suddenly got more advertising and a greater audience from that. It just grew from there.

Micah Loewinger: The paper was, roughly speaking, divided into the front of the book, which was the news coverage, and the back of the book, which was more arts and culture. One of the early news reporters is this amazing woman, Mary Perot Nichols, who started at the paper in 1958. Her origin story at the paper, it turns out, is not that unusual. She just walked in through the front door, right?

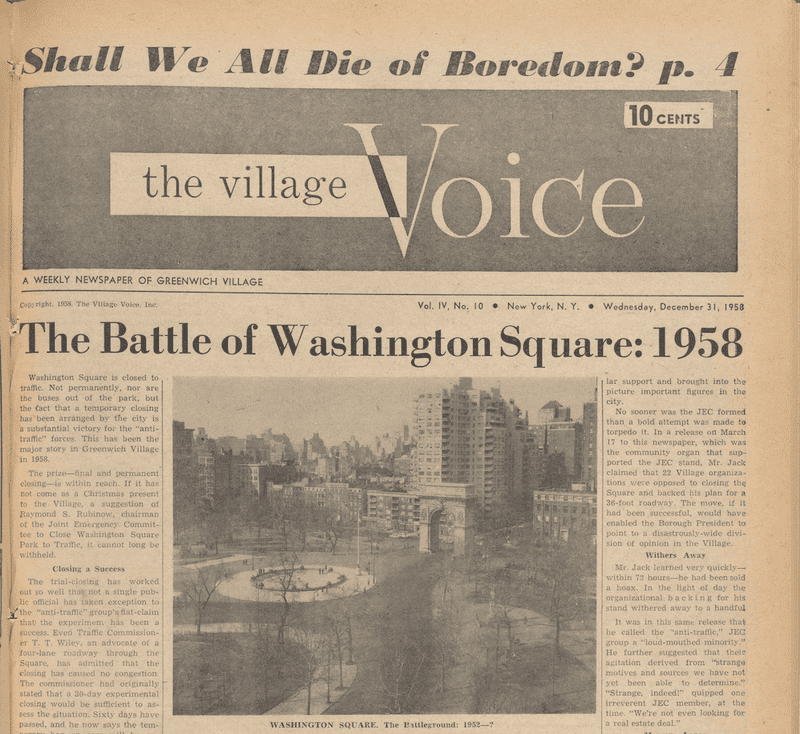

Tricia Romano: Yes. [laughs] That's what a lot of people did. They just would walk into the office, they would just come in and be like, "Hey, do you know about this thing? Or, why aren't you covering this or that?" She was a mother who lived nearby, and her and a group of other mothers would hang out in Washington Square Park, one of them being Jane Jacobs. This is a time when Robert Moses had this vision for the city that was much more car-centric and would have bulldozed the lower part of Manhattan as we know it now. She began going into The Voice of saying, "Why aren't you covering this?"

After a few tries, they said, "Why don't you do it?" She had literally no reporting skills and had never done that before, but she apparently loved the research, and she loved the hunt.

Micah Loewinger: Robert Moses, of course, was an incredibly powerful urban planner in New York City for decades. What happened to his attempt to turn the beloved Washington Square Park into just another thoroughfare?

Tricia Romano: Well, a lot of what Mary did was advocate against it every week in The Village Voice and getting the neighbors involved, especially a lot of the women who were using that Park every day with their kids to block it. Eventually, politically, she was able to convince a lot of the mafia, store owners also. She would put it to them like, "Look, you know all those people that pay tribute to you, you meaning all the people they got money from, they're not going to be there anymore. None of those stores will be there. That restaurant won't be there, so you're going to lose money.

Micah Loewinger: The offices of The Village Voice were right next to the Stonewall Inn. Voice reporters were there in 1969, and covered when the bar was raided in an event that sparked the modern-day gay rights movement. How did The Voice cover the Stonewall uprising, and why were they targeted by the gay rights movement in the so-called Zaps?

Tricia Romano: Back in the day, gay bars were not allowed. Also, I should say, most of the gay bars, if not all of them, were owned by the mafia. It was this game that the police and the mafia would play, which was, they'd go raid the gay bar, and the mafia would pay off the police, and then the bar would reopen. In this case, they were raided and the patrons were fed up, and they started getting roughly handled by the police outside. Howard Smith went inside. He was a nightlife reporter on the scene in the '60s and '70s. He was inside with the police and Lucian Truscott [unintelligible 00:11:02] from the outside.

They were both straight white men. The way they covered it was both with more seriousness and length than you would see in any other publication. There were two probably 1,200 word something articles inside the paper, whereas any other paper, I think, maybe ran a little squib, and no one was there. They used words that we would find offensive today.

Micah Loewinger: The headline was Forces of, and then the F slur, that's offensive today, but it was offensive then too, and gay readers of the news coverage were not happy with it.

Tricia Romano: They were not happy with that, and they were also not happy with the fact that The Voice wouldn't take ads that said the word gay, so they were zapped. Zapped meaning protested. The Voice's offices were pretty transparent. The windows, I think, were showing to the street. They just disrupted the meetings and such long enough that Dan Wolf, the editor-in-chief, was like, "Okay, I guess we got to deal with this." That was a learning lesson for The Voice, and it happened much sooner than it did for other media.

Micah Loewinger: One of the internal agitators at The Voice, who was quite critical of the homophobic language that was used in its coverage of Stonewall, was Richard Goldstein, who you've already mentioned. He was arguably the paper and America's first real rock critic. He was a gay man, who helped shape the music writing of the paper.

In addition to Goldstein, there was Robert Christgau, who joined in the late 1960s as a rock critic and columnist. He went on to be the paper's longtime music editor. He jokingly referred to himself as the, "Dean of American Rock Critics," which would be this nickname that would follow him around for the rest of his career. These guys hung out around The Village, including the iconic bar and venue, CBGB, where they hung out with Lou Reed and Patti Smith, and saw early shows of Blondie and the Ramones.

Tricia Romano: CBGB was not very far away from The Voice's Office. It was where you went to see local bands' great new music. Those bands just happened to be legendary, or they would become legendary, in part, because The Voice was shining a light on them. They weren't the only one, but they were certainly the local outlet to do that.

Micah Loewinger: Robert Christgau would later become known for his consumer guides, where he gave new albums a letter grade, like A, B, or C, or whatever. As one of the men you quote in the book describes that Christgau was hated by bands. There's a famous live performance of Walk on the Wild Side by Lou Reed from 1978. He's vamping while playing the song. He says this about Robert Christgau.

Lou Reed: Imagine working for a year on an album and you got a B+ from the a**hole on The Village Voice. You don't got to say …

Tricia Romano: I've never heard the whole thing. That's amazing. The thing about Bob, which is different than a lot of music writers, is that he did not want to be friends or friendly with the bands, because his graph exterior belies a very soft interior. If he liked somebody as a person and then hated the record or had to be critical of it, he felt bad. He found it easier to be just completely apart from the band.

[music]

Micah Loewinger: Coming up, multiple ownership changes herald the beginning of the end for The Village Voice. This is On the Media.

[music]

This is On the Media. I'm Michael Loewinger. We left off our story about the history of The Village Voice at the end of its early heyday of the '50s and '60s. In 1977, after passing through several different owners, The Voice was acquired, to the great chagrin of its writers, by media mogul, Rupert Murdoch. The staff ended up unionizing and scoring some surprisingly progressive wins. Here's Tricia Romano.

Tricia Romano: The Voice was part of a package. It was New York Magazine and The Village Voice. Rupert Murdoch didn't really want The Village Voice. He wanted New York Magazine, but come to find out New York Magazine is actually not the moneymaker, The Voice is. When he took over, the New York Magazine staff was fired, and The Voice staff freaked out and formed this union. After a few years, they're talking about health care at a union meeting, we had a thing where if you had a live-in partner, they could be on your health care.

Micah Loewinger: Somebody that you're dating, but who you're not married to?

Tricia Romano: Yes. That was a big thing in their negotiations to get spousal benefits for unmarried couples and extend that to gay couples, and they got it. Murdoch was like, "You may not trumpet this." The lawyer was like, "Oh, no, but they are going to trumpet this. They're going to trumpet it specifically."

Micah Loewinger: You mentioned that Rupert Murdoch saw that The Village Voice was more of a moneymaker than New York Magazine. How did the paper make real money?

Tricia Romano: The classified ads in the back of the paper were basically a form of printing money. That was a source of income for decades for The Voice. For a long time, people would line up at Astor Place on Tuesday night, waiting in line to get the first edition of the paper so they could get a jump on apartment ads.

Micah Loewinger: There was this quote from Jackie Rudin in your book, who worked in advertising who said--

Jackie Rudin: People found their lives through The Village Voice, whether it was a partner, or a job, or an apartment, or whatever.

Micah Loewinger: Blondie and Bruce Springsteen and the E Street Band found their drummers through classified ads in The Village Voice.

Tricia Romano: Max Weinberg was like, "The Village Voice changed my life."

Micah Loewinger: Who was auditioning to be Bruce Springsteen's drummer.

Tricia Romano: That's where you would post. There was no Craigslist. There was no Facebook Marketplace, no Twitter. There was nothing like that, where you would post your help wanted ads. Musicians did the same thing as some office looking for a secretary.

Micah Loewinger: Your book outlines this rift at the paper between the mostly white male reporters, who covered the news for the front of the book, the so-called white boys, as they were known, and the feminist and gay writers, who mostly covered arts and culture in the back of the book. You wrote about this really interesting episode in 1986, when Robert Friedman, the editor of the paper, made the call to put performance artist, Karen Finley, on the cover of the paper.

Tricia Romano: The article was written by Cynthia Carr, who went by C. Carr. She had had a column about performance art for several years. She came to Richard Goldstein and her editor, Karen Durbin, and said, "There's this performance artist I really want to cover. She's pretty controversial. I think you should come see her." The thing that she was known for was using food. She would often be naked, or partially naked, or wear little prom dresses, and she would crush canned yams on her body while she had this incantation possessing the male voice.

Cynthia Carr writes this story, and they decide to put it on the cover. She was just posing with her dog. It's a very pretty cover shot, but you have to realize back then, papers are finite, and space is finite, and so what gets on the cover is a big thing. It's a big deal. At the time, Pete Hamill, who's one of the famous columnists in New York journalism, worked at Daily News, he was a star. He led this charge against this piece, because he saw it as unworthy of being on the cover because it wasn't real journalism in his eyes. It diminished the hard news that all the guys in the front of the book did.

He never even saw the work, but he wrote a full page denouncing the story, and the work, and the idea of the artt that she was doing.

Michael Loewinger: Obscenity seemed deliberate in this performance. Do you want to describe what she was doing with the yams?

Tricia Romano: It was sexually explicit and meant to be provocative. It was a commentary on the male gaze and objectification of women, et cetera. It's just the kind of thing that those guys, it just is going to go over their heads. They led this charge. It was him, Nat Hentoff, Barrett, Newfield.

Michael Loewinger: These are some of the heavy hitter investigative reporters.

Tricia Romano: All these guys were like titans at the paper by this time. They go marching in and say, "How can you put this filth on the front?" Not really understanding that their city was very different from the city that Cynthia Carr was in. The Voice was a reflection of the moment that New York was in. The front of the book left graffiti in the office, in the bathroom. They left cans of yams everywhere on desks and around the cubicles. It was childish. The more upset the back of the book got, the more the front of the book would push it and vice versa.

It's interesting to note that the front of the book wasn't as big, literally space-wise as the back of the book. The back of the book was all the listings and the film reviews and the music and the theater and art and dance, all of it. It just didn't make the cover as often. Cynthia Carr was like, "If it hadn't made the cover, I don't even know if they would have realized it was in the paper." Because it was on the cover, they were furious.

Michael Loewinger: You're describing this tension at the paper, and reading the book, it felt to me like there was this constant hum of struggle. Where on one hand, you have The Village Voice as this very radical, very progressive paper, and yet we keep seeing moments where it's failing to live up to its own values. On one hand, the paper is celebrating great Black music, and on the other hand, there were very few people of color writing for the paper in its first couple decades.

The paper was among the first to write about abortion. It had this great stable of feminist writers like Ellen Willis, Laurie Stone, Karen Durbin, and M. Mark. Yet, internally, they face derision from their own colleagues. The paper had these pioneering gay writers, even as The Village Voice is publishing homophobic slurs in its coverage of the Stonewall Uprising.

Tricia Romano: It was a constant learning process, I think, for the people on the paper and the people reading it, right? The fact that they didn't really have any Black writers until Stanley Crouch shows up, is crazy. I think it was 1976 or something.

Michael Loewinger: Basically 20 years in.

Tricia Romano: Yes. They wrote about Black causes. Wayne Barrett, the reporter that covered Trump and Giuliani, and Jack Newfield, who wrote about worst landlords and the worst judges, and Nat Hentoff, who got his start writing about jazz, they were all very much about civil rights and were a big part of that movement. They were blind to the fact that there were really no Black people at the paper, and no one seemed to figure that out. Schneiderman, David Schneiderman, who was an op-ed editor at The New York Times in the '70s, comes on board, and he's the editor-in-chief, and he says, "What? This is the progressive village voice, and there are no Black people on staff?"

Then they also got investigated by a government agency for this, so they had to take action. Right around that time is when hip-hop is born. Hip-hop helped usher in a whole bunch of Black writers into the paper. Carole Cooper, Barry Michael Cooper, not related, they're covering hip-hop. Later, Barry Michael Cooper becomes more of an investigative reporter and covers the crack epidemic and does the story that is New Jack City that becomes the movie. Hilton Alves joins the paper. He is a Pulitzer Prize-winning critic now at The New Yorker. For decades, there was nothing, and it still was a very, "white paper," even towards its end.

Michael Loewinger: I'm going to jump way ahead to the 2000s [laughs] when we're starting to see cracks in the village voice, its business model. Anil Dash, now a famous technologist and writer, joined the village voice in 2001. This is when Craigslist, the classified ads website, was first becoming a thing. Then 9/11 happens. How did the internet and 9/11 converge to ruin The Village Voice's whole business model?

Tricia Romano: Anil gets to the voice in the summer of 2001. It happens to be the summer that Craigslist is about to hard launch in New York. He came from San Francisco, and he knew what was coming. He's telling them, "You guys, we're about to get disrupted in a major way." People ignored this.

Anil Dash: The second workday, my third day there, Craigslist launched in New York. I'm just talking to somebody. I'm like, "Hey, what are we doing about Craigslist?" It was like, "Who's Craig? What are you talking about?" I couldn't articulate why it mattered so much. I couldn't tell people, a whole world is about to change. I felt like Chicken Little. You know what I mean? I kept running around being like, the internet is coming. It was just because it sounds crazy, right? You sound like a crazy person.

Tricia Romano: Then 9/11 happens. Google News wasn't a thing yet, but people wanted immediate information at that point. That's when people started pushing out news a lot faster online. The combination of those two things starts to render print not necessarily useless, but slow. When 9/11 happens, there's a little bit of a recession, and the apartment ads stopped being placed with the same level and the same numbers that they were before. Then you have Craigslist saying, "Hey, you don't need to mail in or call anyone or fax your listing to some number. You can just post it directly online, and it's free." A lot of people just shifted to that, and the apartment ads never recovered after that.

Michael Loewinger: In 2005, Village Voice Media, which at this point was owned by a financial management group along with six other alt-weeklies, merged with the New Times, a newspaper chain. They became the biggest company of alt-weeklies with 17 papers. The New Times had long coveted the Village Voice but once it bought Village Voice Media, it started picking it apart limb by limb.

Tricia Romano: It was like they just wanted the logo and the name, but that logo and name only has value because of what was there when you bought it, this collection of voices that made it the Village Voice. Those voices changed. Some people came and went, but there's a core sensibility that they just didn't get.

Michael Loewinger: In 2017, the print paper for The Voice was shut down. A year later, it seemed like the digital version was dead, too, until 2020 when it was revived by a new crop of ownership. I think we can confidently say that The Village Voice of old is gone. What's the latest iteration like?

Tricia Romano: It's a zombie. The Voice, to my knowledge, only has one employee, and that's R.C. Baker, who is essentially the editor, and they run some freelance pieces. It's just sort of there, [laughs] It's not present in the city the way it should be. The Voice was a guide to a specific life in New York City at specific times. That collection of knowledge from people who cared about what they were covering with such intensity that there were fistfights and brawls inside the paper, that's gone.

Michael Loewinger: Tricia Romano is the author of the new book, The Freaks Came Out to Write. Tricia, thank you very much.

Tricia Romano: Thank you for having me.

Michael Loewinger: Coming up, the story of one foul-mouthed editor and his empire of muck-raking dirtbags. This is On The Media. This is On The Media. I'm Michael Loewinger. As we just heard, The Village Voice was bought by a national chain of alt-weeklies called The New Times, owned by a man named Michael Lacey. Over four decades, Lacey and his business partner, James Larkin, built the largest, most influential company in alternative media. When Craigslist came along, Lacey and Larkin launched their own classified website to head off the same disaster that was taking down newspapers left and right.

Backpage, as it was called, soon became synonymous with sex and scandal. The Justice Department was paying attention, and in 2018--

News clip: The government cracked down on sex trafficking. Federal agents this afternoon seized the classified ad website Backpage.com and closed it down.

News clip: Seven people were arrested including the site's founders. Tonight they are facing federal charges including prostitution and money laundering.

Micah Loewinger: Lacey, now 75 years old, has already been tried twice. The first was declared a mistrial, and the second last fall found him guilty of one count of money laundering. The other 84 accounts were dropped. He now faces a third trial this summer. A new podcast series from Audible called Hold Fast documents how Mike Lacey in his own telling became the Larry Flynt of the internet age. The hosts three former New Times journalists conducted a series of interviews with their former boss to tell the story of the rise and fall of backpage.com. What follows is an excerpted version of episode one. Sam Eifling kicks it off, then you'll hear from Trevor Aaronson, followed by Michael Mooney.

[music]

Sam Eifling: Lacey is in his mid-70s, light blue eyes, a nose that looks like it's caught more than a few punches. He wears designer black thick-rimmed glasses, and sports tattoos on his hands. He looks like a magazine editor sharing a body with a barroom brawler, and actually, that's what he is. If he ever charms you into forgetting his brawling half, just read his knuckles. Tattooed across the business part of his fists in faded blue ink are the letters H-O-L-D F-A-S-T, Hold fast. It's a traditional seafarer's tattoo. Hold fast tells other sailors that you can grip a rope through any storm. It tells them, they can put their life in your hands, that you'll never let go.

Trevor Aaronson: Lacey's newspaper career began on the campus of Arizona State University, where he and other students founded an anti-Vietnam War paper in 1970. They called this new paper, Phoenix New Times. For the first edition of the paper, Lacey covered a Vietnam War protest. A number of construction workers had showed up as counter-protesters.

Mike Lacey: I'm sitting up there with the construction workers.

Michael Mooney: This is Michael Lacey.

Mike Lacey: This guy, I'm interviewing him and he says, "Excuse me, I'll be right back."

Trevor Aaronson: The guy walked down the field and up to a man who'd organized the demonstration.

Mike Lacey: He hauls off, sucker punches him, knocks all his teeth out, and drops him like a sack of potatoes unconscious. Then the guy walks back up to finish the interview with me. I'm thinking, "Well, that's more je ne sais quoi than I've ever seen in my entire life. My God." That was our first story in the first issue of it was the New Times. That was the beginning.

Trevor Aaronson: Jim Larkin joined the paper two years later, and ran the business side, as New Times built a reputation for aggressive renegade journalism. From that one newspaper in Phoenix, Lacey, and Larkin bought up papers until they had the largest chain in the history of alternative journalism, spanning The Nation, from LA Weekly in Los Angeles to the Village Voice of New York, from Seattle Weekly to Miami New Times. At its height, Lacey's newspaper chain generated close to $200 million in annual revenue.

Alternative weekly papers or alt-weeklies, as they're often called, were usually free and distributed at bars, restaurants, and on street corners.

They varied in style, but there was a general template. Provocative cover, news coverage up front, a long narrative feature, food and arts coverage in the middle, a robust music section, and finally, in the back pages, loads and loads of classified ads. Some of these classified ads in the back of all weeklies were written in coded language, though it wasn't hard to decipher. They advertised sex work, some of it legal, some of it not. The editorial tone of these newspapers was skeptical, impolite, anti-establishment. The paper was created in Lacey's own image.

Mike Lacey: Right [unintelligible 00:34:09] I'll kill you. Then you just can't do 5000 words off the top of your head. You got to put some sweat equity into this goddamn thing. No one's saying it's easy. Get off your ass and do it.

Sam Eifling: We realized something about Lacey watching it first from afar, and then up close as we interviewed him over the past three years. He's a larger-than-life presence, hounded by the government, who made fortunes as a public outlaw. Lacey is just the character we would have killed to cover when we were working at New Times.

Michael Mooney: Trevor, Sam, and I worked at the alt-weekly in Fort Lauderdale, Florida, north of Miami. Our jobs at New Times were amazing. We lived in this beach town full of crazy people doing crazy things. Sometimes we'd report our stories, type up our drafts, then maybe go to the beach, share a joint, and read each other's work. New Times had a corporate culture that wasn't very corporate, at least not in the ways any of us were accustomed to before then. It wasn't exactly sex, drugs, and rock and roll, but it wasn't that far off either. Somehow this culture at New Times papers fostered some of the most interesting and important investigative reporting in America.

New Times writers nationwide held local officials and agencies accountable and covered marginalized communities otherwise ignored by traditional media. Powerful people lived in fear that one day they'd get a call or a knock on the door from a New Times reporter. That was all part of the corporate culture too. Inside New Times offices around the country, reporters would talk about powerful people as if they were big game. Who head could you mount on the wall?

Trevor Aaronson: I left New Times in 2006, 18 years ago now, a journalistic lifetime. For years, I didn't give New Times and its founder much thought, but then something strange happened. In September 2016, a decade after I left the company, I received an email from a lawyer in Arizona asking for my mailing address. The email claimed Lacey was building a database of former employees, so I replied with my mailing address figuring, "What the hell? Maybe I'll get a holiday card."

Then, a couple of weeks later, I got a check in the mail for $5,000. It was a gift from Lacey. Turns out Lacey, facing the possibility of serious federal charges and asset seizures, threw up a middle finger at the Justice Department. He became millions less rich, by sending $5,000 checks to many of the journalists he'd once employed. Word quickly circulated among Lacey's former reporters.

Michael Mooney: "Did you get a check? What's Lacey up to? Did you hear who didn't get a check?"

Sam Eifling: The checks were so mysterious, no details, and lots of former employees didn't get one, like me. It was classic Lacey, showing real appreciation for his writers, while also drawing them into something that might be less than legal. Okay, let's go back in time, to the age of the daily paper. Maybe you remember those bundles of dead trees thrown at your front door by a kid on a bicycle. For years, your hometown daily paper enjoyed a near monopoly on both news and advertising. Even a mediocre daily could turn 20%, 30% annual profits, so big corporations bought up American dailies and domesticated their newsrooms.

The resulting papers were often bland by design like the suburbs. If you reported for a daily and tested the limits of its inoffensive voice, an editor would remind you that this was a family paper. There were no drugs in the daily except when cops arrested people. There was no swearing in the daily, not even in a quote. The daily's outlook was and is more white or heterosexual, more moneyed, and more little see conservative than America at large.

Michael Mooney: To borrow a phrase from tech, the dailies were ripe for disruption. Alternative weekly newspapers arrived on the scene as that disruption. Alt-weekly newsrooms attracted a particular cast of journalists, culture writers, who found dailies too state, aspiring novelists and screenwriters who wanted to write non-fiction with bravado, hard news junkies, who crawled the city like a tapeworm.

More broadly, the alts got writers who, for one reason or another, chafed inside institutions. The fact is, without an institution backing you, you can't get much done in journalism or life. The alts built robust papers around calling bull [bleep] wherever they saw it. Along the way, they tried to enthrall or delight or enrage everyone in town.

Trevor Aaronson: If this sounds like a dream job to you, and if you could tolerate making less money than anyone else in your college graduating class, then congratulations, you might have had the makings of an alt-weekly journalist.

Sam Eifling: As a subspecies of alt-weekly, Lacey's New Times papers were also smart, and weird, and contrarian, but the papers we worked for, also had certain other traits. For one, they were not as reliably left-leaning. For another, they were fiercely investigative, even when covering, say, musicians or athletes, they went digging for dirt. They also had in hindsight, a cigar-chomping, testosterone-fueled bravado about them, like a divorced uncle who insists you punch him in the gut as he flexes his abs and then buys you a shot.

Michael Mooney: 15 or 20 years ago, what made this dirtbag dream possible, was the business side, how the operation made money. Now, as a reporter, usually you don't really even want to know how the business works. You might even try to avoid seeing the ads that run next to your stories because part of being as fair as possible means you want to treat everyone and every business equally. You don't want to know who's actually paying your salary, but at an alt-weekly, it was really obvious. The paper was free, so it made money from advertising.

Advertisers were restaurants, bars, national beer distributors, that type of thing, but like the dailies, a lot of the advertising revenue came from the classifieds. Classified ads charged by the word, and you could fit a lot of words on a page of newsprint. A single page in the 80's or 90's might rake in more than $20,000 at a big weekly, and they could print page after page after page with those tiny ads, 10-point font. They were a huge moneymaker.

You'd find classified ads in every kind of newspaper all over America for decades. People selling boats or hiring bartenders or renting apartments. Sometimes they were even personal ads, like a primitive form of dating apps. One person places an ad explaining what they're looking for. Single man seeks a lady who wants to travel the world. Married woman, seeking a friend to visit art museums. New Times ran those too in the back pages of every issue. Boats for sale, apartments for rent, personals, all that, but alt-weeklies ran some slightly more adult versions too.

Trevor Aaronson: They had an entire section of the personals for escorts. They didn't explicitly advertise anything illegal, but everyone understood what they were selling. The company called it adult advertising.

Jim Larkin: I'm not quite sure how you define adult advertising.

Trevor Aaronson: That's Jim Larkin, Mike Lacey's business partner. Larkin ran the business out of the newspapers and later backpage.com. He was arrested by the FBI the same day Lacey was.

Jim Larkin: I guess, gosh, advertising to meet people, meeting other people, massage, strippers, those kinds of ads.

Trevor Aaronson: An ad in the back of a New Times paper might say something like M for M or M for W to indicate that a man is looking for a man, or a man is looking for a woman, innocuous enough.

Michael Mooney: Or an ad might feature an MWC seeking an SBF for an NSAONS. That would be a married white couple looking for a single Black female for a no strings attached, one night stand.

Sam Eifling: If you saw a woman advertising a GFE, that's girlfriend experience, or any number of enticing massages at her place or at yours, well that might be a consenting adult seeking another to exchange physical pleasure for US dollars. Adult ads like these have always existed at the edge of First Amendment protection. Because the language used was often ambiguous, and the specific services offered for money a bit unclear, publishers had a level of deniability that meant these ads were protected by free speech rights. The government couldn't prove these publishers knew the ads were advertising illegal services, so the ads were legal, protected by the First Amendment.

Federal judges have ruled that if the government banned ambiguous ads, it would deprive rights from the people who aren't selling sex. In a gray zone, everyone gets to speak, so it was in the newspaper's interest to keep things hazy, but it was no secret that sex workers advertised in the back pages of alt-weeklies. We all just accepted this, including police and prosecutors. If the world's oldest profession advertised in the back pages of papers that you could find at bars and clubs, well then whatever.

Michael Mooney: That blind-eye approach started to shift in the mid 90's when Craig Newmark created a website that allowed people to post classified ads for free. He called it Craigslist. He charged car and furniture dealers and for help wanted in real estate ads. Everything else, whether you were selling your couch or renting out your bicycle or leasing access to your body, that was all free. Craigslist, a homely no frills website sucked the marrow out of American journalism.

In 1995, newspaper classified ad revenue in the United States totaled about $12.5 billion. Craigslist cut a gaping hole in that money bag. Mike Lacey and Jim Larkin started their own website to compete with Craigslist so they could maintain the classified ad business and keep part of that money.

Jim Larkin: We started, in 2004, Backpage, because we knew that the classified business was going away in newspapers. That's what we did.

Sam Eifling: Backpage.com, the new site looked a lot like Craigslist. It had the same categories, the same types of ads, cars for sale, apartments for rent, job ads. It wasn't as big as Craigslist, not even close really, but it was growing.

Jim Larkin: We were off to the races.

Sam Eifling: Just like the ads in the back pages of the papers, Backpage ran ads for escorts and for other sex workers. The ads even used many of the same thinly veiled codes as the classifieds in the back pages of the alt-weeklies.

Jim Larkin: Our strength was adult. That's the way Backpage started.

Michael Mooney: Within a few years, Backpage was in every city in America, just like Craigslist, and wouldn't you know Backpage was minting money while we were reporting at New Times papers. We may not have worked for Backpage, but as writers for Lacey and Larkin's newspapers, it helped to cover our paychecks.

Trevor Aaronson: Ultimately, Backpage became a problem, a legal problem for Mike Lacey and Jim Larkin. For decades, police and politicians and moral crusaders tolerated the ads in the back of all weeklies. Small protests popped up here and there. Police ran stings targeting sex workers and Johns now and again, but nobody clamored to shut down all these alternative newspapers nationwide. Backpage was different. As it grew to 30 million ads a year worldwide, the site started getting the attention of some very powerful people.

Kamala Harris: Backpage.com needs to shut itself down.

Trevor Aaronson: Before she was the Vice President of the United States, before she was a US Senator, Kamala Harris was the Attorney General of California, and back then, she took direct aim at Backpage.

Kamala Harris: When it has created as its business model, the profiting off the selling of human beings and the purchase of human beings.

Trevor Aaronson: After Kamala Harris became a US Senator, she and other senators pushed an extraordinary bipartisan effort to pressure the Justice Department to go after Backpage. Lacey and Larkin were called to Capitol Hill to testify. The Justice Department came down on them with allegations that they were profiting from sex trafficking.

Mike Lacey: They don't scare me. They just don't [bleep] scare me. They've been after me for [bleep] ever. We were told this was legal, told repeatedly it was legal. We've had judges, federal judges rule that it was legal, and now they still want to put us away. Well, take your best shot.

Michael Mooney: When Lacey was thrown in jail after that FBI raid, they told him he couldn't be in the general population for his own safety, so they took him to a solitary cell. In that cell he found a book. The book was The Guns of August by Barbara Tuchman, published in 1962. It's a celebrated Pulitzer Prize winning history of the start of World War I. Turns out it's a book that Lacey knows well. It's a book he used to hand out to his writers.

Mike Lacey: I'm sure the writers said, "What the [bleep] is he talking about? He flew all the way down here to tell us this kind of horse [bleep]? Okay, what does this have to do with getting the story?"

Michael Mooney: The Guns of August explains that Germany and France knew a war was inevitable. Both sides prepared to beat the other for decades, and both sides convinced themselves that they'd win. Germany had a massive army and the biggest guns the world had ever seen. France, meanwhile, was certain it could thwart a German invasion through its sheer Frenchness. France's plan was basically, "Come at me, bro."

Trevor Aaronson: Lacey randomly finding The Guns of August at his darkest moment sounded like a setup for a New Times story, a lucky detail that gestures toward this bigger truth.

Michael Mooney: We nudged Lacey to pick up the metaphor. Are you France or Germany?

Mike Lacey: I'm Belgium.

Michael Mooney: Okay. [laughs]

Trevor Aaronson: Germany told neutral Belgium to lay down arms and let German forces pass through to France or else-- Instead the Belgians swallowed hard and fought back. The Germans marched through anyway pulverizing Belgium, an atrocity that galvanized other countries, including the US to join the fight. That's what really got World War I going, Belgium's valiant stand against an unstoppable machine.

In Lacey's read, he isn't France. We are France, you, me and billions of people online, everyone that uses Facebook, Instagram, TikTok, Reddit. Politicians want more say over who can do what on the internet. They've proposed laws that would restrict what platforms and users can post, but clearly the US government isn't throwing the book at say Mark Zuckerberg and Meta. That would mean confronting an army of lobbyists and lawyers and a user base that includes a majority of Americans.

Michael Mooney: In Lacey's read, the government is hitting him instead. The smaller target, the would-be pushover.

Sam Eifling: To Lacey, the Backpage case isn't really about Backpage or prostitution or sex trafficking or the gray areas of advertising sex work. To him, the prosecution of Backpage is really about free speech online. The US government is aiming its unstoppable machine at the larger internet. You know who's standing in the way? Mike Lacey. Whether or not you agree that Mike Lacey is a martyr, he is right about two things. He is absolutely outmatched. Yet, by fighting back anyway, he has the whole world watching.

?Michael Mooney: Belgium, it didn't work out super well for Belgium.

Mike Lacey: It hasn't worked out super well for me. [laughs]

[music]

Micah Loewinger: Sam Eifling, Trevor Aaronson, and Michael Mooney are the hosts of Hold Fast, a brand new nine-part series from Audible. Listen wherever you get your podcasts.

[music]

That's it for this week's show. On The Media is produced by Eloise Blondiau, Molly Rosen, Rebecca Clark-Callender, and Candice Wang, with help from Shaan Merchant. Our technical director is Jennifer Munson. Our engineers this week were Andrew Nerviano and Brendan Dalton. Katya Rogers is our executive producer. On The Media is a production of WNYC Studios. Brooke Gladstone will be back next week. I'm Michah Loewinger.

Copyright © 2024 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.