Empire State of Mind

BROOKE GLADSTONE: From WNYC in New York, this is On The Media. Bob Garfield is off just one more week, I'm Brooke Gladstone. Last week, dear listeners we set off together on a journey to chart some key differences between America's founding notions of itself–and reality. Last week the subject was the frontier, the official idea of frontier as the birthplace of American individualism, versus the revisionist view of it as a safety, valve facilitated by the state to divert the poor from waging war on the rich.

GREG GRANDIN: Ceaseless expansion. That there is no problem caused by expansion that can't be solved by more expansion.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Greg Grandin, author of The End of The Myth, laid out in vivid detail how the nation's psyche and politics were forged in the shadow of that ever advancing continental frontier–that is, until we hit the ocean. Now we pick up the story with another American conceit, that we are a republic, a union–if an imperfect one. Turns out, that was almost never so. This week we moved deeper into that history with Northwestern University history professor Daniel Immerwahr, author of How to Hide an Empire: A History of the Greater United States. He was launched on the back by a trip he took some years back to the Philippines. He was stunned by what he found–streets with American names, people speaking American English. As an historian, he knew that the Philippines were once annexed by the United States but realized, until that moment, truly understood what that meant.

DANIEL IMMERWAHR: I realized that the United States that I was teaching a history of, was a truncated version. It was the contiguous United States. What people and territory sometimes called the mainland. But that's not the whole country and it's never been the whole country.

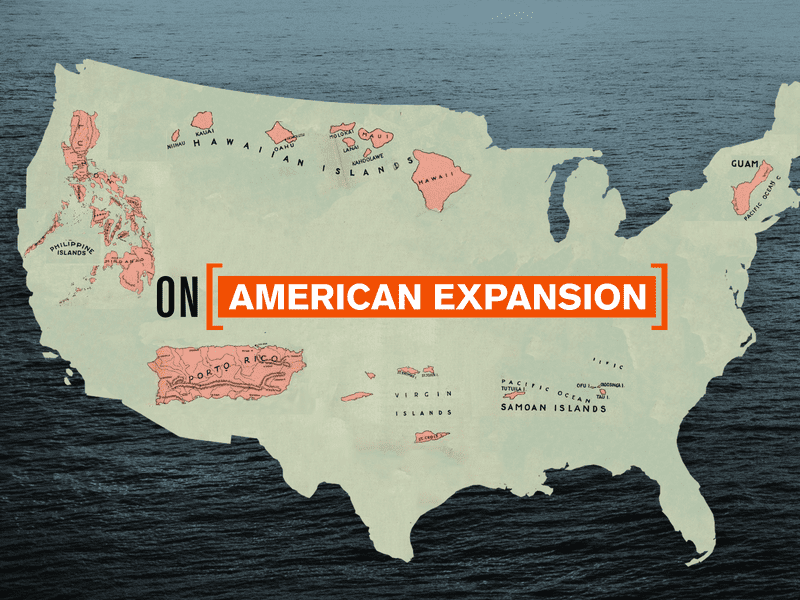

BROOKE GLADSTONE: That whole country is represented by what Immerwahr calls the logo map. You know, the lower 48 spanning from coast to coast, jutting out in the southeast with a protrusion for Florida and a smaller one for Texas.

DANIEL IMMERWAHR: So that map, the contiguous blob with oceans on either side and Canada and the north and Mexico on the south, that's only been the borders of the United States for three years of its history.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: To illustrate how some of us never got past the truncated version of history we're all taught in our formative years and the implications of that, we need look no further back than the past week.

[CLIP]

MALE CORRESPONDENT: The White House spokesperson calls Puerto Rico that country, while defending the presidents treatment of the U.S. territory. We're back in a moment. [END CLIP]

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Puerto Rico's status says belonging to the United States seems to be thoroughly misunderstood by vast swaths of our nation. To see how we arrived at this point, we must journey back to the 19th century when the population boom and our soil was dangerously depleted. Turns out nitrogen is the best remedy for pooped posture and the best source happens to be poop of the avian variety.

DANIEL IMMERWAHR: In the 19th century, that bird poop, guano, was called white gold because it was seen as so valuable as fertilizer for farms that, once they've converted to industrial farming, we're losing a lot of their fertility. An acre of farmland that might formerly have grown 20 bushels of wheat was, by the mid and late 19th century, growing down to 10 bushels an acre. This is a serious crisis.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: You need lots of usable nitrogen and there are whole islands basically made of this white gold.

DANIEL IMMERWAHR: Islands in the Pacific in the Caribbean that don't get a lot of rain but they do get a lot of visits from birds. And then they poop on the Islands year after year after year. And it piles higher and higher, bakes in the sun so that over centuries, you're looking at an island that is basically made out of fecal matter. I asked some historian friends what do you think is the worst job in the 19th century to have and I think I can now say with confidence guano mining is the worst.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Wow.

DANIEL IMMERWAHR: Because it's like coal mining with all the pulmonary damage that you might suffer except you essentially have to be marooned on a rainless island where there's only the food the ships can bring with them, very little water supply. Where people are suffering from all kinds of intestinal illnesses as a result. Guano entrepreneurs sell African-American men in Baltimore. A story about the tropical lives that they'll be able to live consorting with beautiful women picking fruit, occasionally shoveling a little guano. But once the men step on that ship, their reality changes. Where else are you going to go? Right? That ship takes to the guano islands, deposits you there. You're under the supervision of a white overseer. You just have to work and to have to pay for their passage. So the second they arrive, they are in debt to their employers and they have to shovel enough guano or blast it free from the islands in order to pay for their return passage.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: These workers were abused terribly. Left tied up in the sun if they violated an order. And then something happens.

DANIEL IMMERWAHR: And to understand it, you have to understand the harsh regime of labor discipline on Navassa Island.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Off the coast of Haiti.

DANIEL IMMERWAHR: Yeah, this is an island that is full of black men who have been deceived. They're not very enthusiastic about backbreaking work in the scorching sun on a jagged island. It's not a shock to me that these men mutiny. Gather some rocks, weapons and some dynamite and they stage a full out riot. And they end up killing five of their white overseers. The papers all report it. Black men have butchered white men. And they're hauled back to Baltimore for a trial.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Which becomes a milestone in America's legal history of imperialism. Ultimately they win, but how?

DANIEL IMMERWAHR: So it's kind of incredible. The African-American community in Baltimore rallies around them and their legal team make this extraordinary argument which is to say Navassa Island isn't part of the United States. And because it's not part of the United States, federal law doesn't apply. And a federal law doesn't apply, how can you try these men in U.S. courts? They're outside of the jurisdiction of the United States. So what this legal team does is it challenges the constitutionality of the idea that the United States can expand overseas. So it goes all the way up to the Supreme Court and the Supreme Court has to decide is the United States the kind of place that can expand overseas. And the court decides that yes, it is constitutional, right and proper, that the United States should expand overseas. So this minor incident on a place that seems very remote from the perspective of the mainland, suddenly lays the legal foundation for the United States is territorial empire.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: But also, doesn't this decision thereby declare that what happens there is subject to American law. And these companies that were mining the guano were also massively breaking the law?

DANIEL IMMERWAHR: That's right. It cuts two ways. If these places are part of the United States, where do they go to appeal for justice? Right? What are they supposed to do when they're being, as they are, clearly abused? Benjamin Harris concludes that, 'OK yes these places are indeed part of the United States but that means that people working on them should have some appeal to all the institutions and courts of the United States.' And he, as a result, takes this issue up and decides to commute the sentence, so they're not sentenced to death, then they have to spend the rest of their lives at hard labor.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: It was the pursuit of guano that forced us, as a nation, to publicly acknowledge that we were going to expand beyond our manifestly destined borders into realms unknown. By 1898, most of America seems all in on this imperialism idea. Maps for redrawn and hung in classrooms across the country. Maps that we certainly didn't grow up with, that showed us America and the world as it truly was.

DANIEL IMMERWAHR: It's an extraordinary moment. In 1898, in 1899, the United States basically goes on a sort of imperial shopping spree. It fights a war with Spain and as a result of that war it takes the Philippines, Guam and Puerto Rico and it briefly occupies Cuba. And at the same time, almost in a fit of enthusiasm, the United States also annexes Hawaii and American Samoa. And cartographers see their opportunity and start publishing these extraordinary new maps. New maps that show the U.S. mainland surrounded by boxes–so Alaska, Hawaii, Guam, Puerto Rico, American Samoa. Why these are so extraordinary, at least for me, is when I saw them I thought, you know, 'I've never seen a map like that.' I've never seen a map of the United States that had Puerto Rico on it. I've never seen a map of the United States that had that box for Guam. But this is a moment, when a lot of people in the U.S. mainland are so proud of this new facet of the United States that they are eager to see it differently. I found books that have titles like The Greater United States, The Imperial Republic. The old way of referring to the country as the United States, the Republic or the union in the 19th century, those don't really work anymore. Because it's now transparently not. Not a republic and not a union. This new polity, quite transparently, has not been created by the voluntary entry of all parts. The Philippines fights a bloody war of independence that we think racks up more bodies than US civil war.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: I remember there was a time when the U.S. was referred to as Columbia in songs like "Columbia the Gem of the Ocean."

[CLIP OF COLUMBIA GEM OF THE OCEAN UP & UNDER].

DANIEL IMMERWAHR: Yeah because Columbia was, in a way that we have the District of Columbia, Columbia was a literary name for the country. And what's striking about this is the literary name that we all have in our heads that really wasn't that often used in the 19th century–America. A lot of people in the 19th century understood that if you were speaking of America, you were speaking of the Americas–the whole region. That changes in 1898 partly out of this desire to find a new way to describe the country–a new shorthand for it. America, it's a vaguer more expansive term and the president who takes office after the war with Spain, Teddy Roosevelt, uses the word America in his inaugural address. And there's a two week period where he uses it in different speeches more times than every past president has used it collectively in the entire history of the country. And ever since then, it's off to the races.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Why was 1898 an imperial shopping spree? What was going on?

DANIEL IMMERWAHR: The United States bonked into the Pacific. The census in 1890 had issued a report suggesting that the frontier was no more. And it inspired a few, such as Teddy Roosevelt, to try to make new frontiers, to find new places where the United States could restore its vigor.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: So explain the Philippines.

DANIEL IMMERWAHR: It partly has to do with Teddy Roosevelt. He's the assistant secretary of the Navy. His boss leaves the office for an afternoon to visit an osteopath, and Roosevelt springs into action and orders the U.S. Asiatic fleet to prepare to invade Manila if the United States has a war with Spain. And his boss doesn't countermand the order, possibly fearing looking weak. And so when the United States does go to war with Spain, it engages the Spanish fleet, defeats it and suddenly the United States has the Philippines on its hands.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Not suddenly, takes a while.

DANIEL IMMERWAHR: Right. The actual conquest of the Philippines takes an enormous amount of time. Part of the reason the United States is in a good position, vis-a-vis the Philippines, is that the United States has allied itself with Filipino insurgents who have been fighting against Spanish colonialism for quite a long time. And they think that they are doing so in the name of liberating their colony with the aid of the United States. They are able to conquer the archipelago. The United States ends the war by purchasing the Philippines from Spain. But then it has to deal with the Philippine insurgents and ends up fighting a long and excruciatingly bloody war. The Philippine archipelago isn't restored to civilian rule until 1913. It was only recently surpassed by the Afghanistan war as the longest war in U.S. history.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: On what grounds did the U.S. go to war for the Philippines. Because the US was still hesitant to say, 'we do this for the sake of empire.' The US was never quite as frank about this as, say, the British were.

DANIEL IMMERWAHR: Well this is a really interesting and rare moment in U.S. history where the leaders of the country will start talking like the British. The reason that the United States needs to fight the Philippines, and fight to retain the Philippines, is in order to civilize and uplift Filipinos. The most famous poem justifying empire, Rudyard Kipling's "White Man's Burden" is written as advice to the United States about what to do in the Philippines.

[CLIP]

ACTOR: Take up the white man's burden. Send forth the best ye breed. Go bind your sons to exile to serve your captives need. To wait in heavy harness and fluttered folk and wild. Your new court sullen peoples, half devil and half child. [END CLIP]

DANIEL IMMERWAHR: Teddy Roosevelt receives an advance copy but a lot of politicians are deeply enthusiastic about this notion that the United States could achieve its adulthood by becoming like Britain, like France–a transparent and forthright empire that's taken on the white man's burden to uplift and to educate its colonial subjects. That's the rhetoric of the time.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: You quote Mark Twain, who had been as ardently imperialistic as Rudyard Kipling, but then reversed himself. Quote 'there must be two Americas. One that sets the captive free and one that takes a once captive's new freedom away from him, picks a quarrel with him with nothing founded on and then kills him to get his land. For that second America,' he proposed adding a few words to the Declaration of Independence, 'governments derive their just powers from the consent of the governed White men.'

DANIEL IMMERWAHR: That's right. Mark Twain and Kipling were friends and initially Mark Twain had been, as he described it, a red hot imperialist. But as he saw the war in the Philippines start to unfold, he came to be one of the most withering critics of the war, just as vociferously anti-imperialist as Kipling was pro-imperialist.

[MUSIC UP & UNDER]

DANIEL IMMERWAHR: And for the rest of his life, he would chronicle with sarcasm, with outrage, everything that the United States was doing in the Philippines. The massacres, the tortures, the hypocrisy.

[MUSIC UP & UNDER]

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Coming up, how the world's professed to leading democracy learned to reconcile itself to imperial brutality. This is On The Media.

[MUSIC UP & UNDER]

*********************

BROOKE GLADSTONE: This is On The Media, I'm Brooke Gladstone. At the dawn of the last century, the arguments over imperialism didn't end with poets like Kipling and writers like Twain. There was a flash in time when it dominated politics and the press. In a world of shifting borders, how should, and how would, the adolescent United States big headed about its democratic values, grapple with the tensions inherent in capturing territory. Historian Daniel Immerwahr says that this vital debate blazed across America's consciousness like a comet–then vanished just as quickly out of sight and out of mind. Presidential candidate William Jennings Bryan speaking out against imperialism in 1908.

[CLIP]

WILLIAM JENNINGS BRYAN: We do not want the Filipinos for citizens. They cannot, without danger to us, share in the government of our nation. And moreover, we cannot afford to add another race question to the race question we already have. Neither can we have all the Filipinos as subjects–even if we could benefit them by doing. For such an inconsistency would paralyze our influence as the world's teacher in the science of government.

DANIEL IMMERWAHR: The racial logic here is totally transparent. And interestingly, a lot of the anti-imperialism was a racist anti-imperialism. The objection to Empire was that it would extend the borders of the United States in such a way that would include more non-white people in the country.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Even during our transcontinental land grab, Americans shied away from taking land that was populated by people who were not white.

DANIEL IMMERWAHR: Yeah it's really extraordinary. So the United States expands a lot as the borders go west but was always operating a logic of the United States should seek to take lands, land that would then be used for white settlers. But it should not seek to incorporate large non-white populations. So after the United States fights a war with Mexico in the 1940s, militarily, it could seize a lot of Mexico. But politicians debate how much of Mexico does the United States really seek to annex? The southern border of the United States was carefully drawn in order to give the United States as much of Mexico as it could get with as few Mexicans.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: People of color cannot be trusted with the vote–that seems to be the governing principle here.

DANIEL IMMERWAHR: That's the operative logic. Yes.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: And yet, didn't we in the Navassa decision that recognized that our off the mainland holdings were still subject to American law mean that the people who lived there had constitutional rights?

DANIEL IMMERWAHR: You might think so. And the Supreme Court has to figure out what to do with this newly shaped United States. And there are a series of contentious Supreme Court cases starting in 1981 called the Insular Cases. And ultimately what the court decides is that constitutional rights apply in the mainland United States but they don't apply in Puerto Rico. And shockingly, this is still law today. You can have rights in Puerto Rico but they're not guaranteed by the Constitution because Puerto Rico exists in an extra constitutional zone. That's one reason, also, why if you're born in American Samoa, you're not a U.S. citizen. You're born in the United States but you're not born in the United States is covered by the Constitution, the 14th Amendment doesn't apply to you and therefore you're a U.S. national.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: But you're not a citizen.

DANIEL IMMERWAHR: That's right. And the history of the United States' colonial empire is the history of a lot of people who are U.S. nationals and either are not U.S. citizens, have to push to become U.S. citizens. And even when they receive that citizenship, for example Puerto Ricans have been citizens since 1917, the citizenship that they receive is statutory–i.e. it's provided by law not by the Constitution which also suggests that it can be taken away.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: One of the most clarifying things that you do in your book is to describe the tri-lemma that placed the central ideas of what the United States is in conflict with each other when confronted with its imperialist role.

DANIEL IMMERWAHR: That's right. In the late 1890s, when many people in the United States are contemplating the future of the country, they realize that they can have an empire. They can have a country that's ruled by white people and they can have a country that has a representative government. But they can't get all three of them.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Why not?

DANIEL IMMERWAHR: Well, because think about it. Because now, the United States includes large non-white populations. So if the United States is going to continue to be Republican, Filipinos should have some kind of representative government and should have some kind of voice in the federal government of the United States. Those are the principles of Republicanism. They are taxed. They should be represented. That seemed like it was a founding and core principle of the country. But there are a lot of anti-imperialists, including William Jennings Bryan, who worry about what happens to the United States if suddenly non-white people have political power. Some people try to solve this one way by allowing the expansion of the United States but by rejecting its Republican principles. That's how Teddy Roosevelt thinks the United States should grow. It should have republicanism for the mainland but not for the entire country. Others, like William Jennings Bryan, seek to resolve this by not having empire, by limiting the growth of the country so that it doesn't have the problem of large, non-white populations who otherwise might need political representation.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: And there's a really loud debate about this.

DANIEL IMMERWAHR: And it's in some ways a tragic debate because those are usually the two positions you hear. The United States should abandon Republicanism or the United States should limit itself to its contiguous borders. What you don't hear in the mainland debate is the third option: the United States should jettison white supremacy.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: They never considered taking white supremacy off the table and yet they managed to reconcile these three incompatible ideas.

DANIEL IMMERWAHR: And largely this happens by not talking a lot about the territory. So if you can brush it under the rug, the United States can still present itself, to itself and to others, as a republic–the distinctive and exceptional world power without being an empire.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: The maps of Greater America start to go away?

DANIEL IMMERWAHR: Literally you can see the boxes erased. If you look at textbooks that are published by 1920, it is really hard to find a map that shows any part of the United States beyond the mainland.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: And in terms of press coverage, let's talk about the invisibility of the people that the U.S. had come to rule. First, statistically.

DANIEL IMMERWAHR: So the census is the statistical self-portrait of the nation. And if you look at the census from 1910, from 1920, from 1930, the first page in the population report will say, 'this is the population of the United States. And here is the population of its possession.' But everything after that in the census–how rural or urban is the population, how long do people live, what kind of jobs do they have–all these ways in which the United States seeks to understand, itself those calculations are implicitly just about the mainland. And the argument is that people who live in the territories are just too different to be included in the calculation. So essentially, they are relegated to the shadows.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: So they're invisible in our numbers, more or less? And they're also invisible in American popular culture. I was struck by your discussion of the films about the long march in Bataan.

[MUSIC UP & UNDER]

DANIEL IMMERWAHR: That's right. So one of the more dramatic events in World War II is the Japanese conquest of the Philippines. And this becomes the single bloodiest thing ever to happen on U.S. soil. World War II in the Philippines ultimately kills 1.5 million people.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Wow.

DANIEL IMMERWAHR: About 1 million of whom are Filipinos or U.S. nationals. That's two civil wars. And there is very little registering of that on the mainland during the war, and frankly, there's very little registering of that now. It's not the kind of thing you find in textbooks. During the war, the thing that you see most about on the mainland is these wars about a fight in the Bataan peninsula.

[MU SIC UP & UNDER]

DANIEL IMMERWAHR: Where Filipino soldiers and soldiers from the mainland were making a last ditch defense of the Philippines against Japan right before the archipelago got occupied and conquered. But what's so interesting about these films is they focus with laser like intensity on the White soldiers.

[CLIP]

MALE CORRESPONDENT: Our club on Bataan took another rap on the chin last night. [CLIP UNDER]

DANIEL IMMERWAHR: So the tragedy of the loss of the United States' largest colony, a tragedy that will lead to the single bloodiest thing that ever happens in U.S. history, this is entirely understood as something that happens to characters who are played by like people like John Wayne.

[CLIP UP]

MALE CORRESPONDENT: By then the Air Force will have won the war, I suppose. Only where is the Air Force? [END CLIP]

DANIEL IMMERWAHR: The Filipino presence is almost completely erased from their perception of World War II, even when it's taking place in the Philippines.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Obviously, if people are viewed as lesser and if they are invisible, they're more vulnerable. Tell me the story of Cornelius Rhoads who was sent by the Rockefeller Institute to Puerto Rico to study anemia.

DANIEL IMMERWAHR: Yeah. Cornelius Rhoads, Harvard trained doctor arrives in Puerto Rico in the 30s. And he regards Puerto Rico as a sort of island sized laboratory. So here's what we know. First of all, he intentionally refuses to treat some of his patients just to see what will happen. He also seeks to induce diseases in others by restricting their diets. He described some of them to his colleagues as experimental animals. He sits down and he writes to a colleague in Boston, one of them most extraordinary letters that I've read in U.S. history and he says, 'I am here in Puerto Rico. It's beautiful except for the Puerto Ricans.'.

[CLIP]

ACTOR: They are beyond doubt the dirtiest, laziest, most degenerate and thievish race of men ever inhabiting this sphere. It makes you sick to inhabit the same island with them. They're even lower than Italians. [END CLIP]

DANIEL IMMERWAHR: This island would be great if something could be done to exterminate the population.

[CLIP]

ACTOR: I have done my best to further the process of extermination by killing off eight and transplanting cancer into several more. The latter has not resulted in any fatalities so far. The matter of consideration for the patient's welfare plays no role here. [END CLIP]

DANIEL IMMERWAHR: He leaves the letter out. It's discovered by the Puerto Rican staff. It seems to confirm all of the fears that Puerto Ricans have about mainlanders and it becomes a scandal on the island.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: And this letter helps to fuel the nationalist movement of Pedro Albizu Campos.

DANIEL IMMERWAHR: That's right. There's already a small nationalist movement in the 1920s. Pedro Albizu Campos is at the head of it. But in the 1930s, economic depression and then the issue of this letter, turned it into a major force in Puerto Rican politics. And Albizu passes this letter around to anyone who will listen. He sends it to the Vatican. The appointed colonial governor who's a mainlander describes it as a confession of murder. So there is an investigation and how that investigation plays out is really telling. First of all, Rhoads just leaves and there's an investigation without him. And Rhoads' defenders say a few contradictory things. He was drunk. He was joking. He was angry. But the point is that he didn't actually kill eight people. So the government, which is staffed by appointed mainlanders, runs an investigation. Finds another letter that is as the governor sees it worse than the first, which is hard to imagine. But we don't know what that letter says because the government suppresses it, destroys it and decides that Cornelius Rhoads was crazy and intemperate but that he didn't actually kill people.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: So maybe he was intemperate maybe he was a little out of his mind. He paid the consequences by being appointed the vice president of the New York Academy of Medicine and in the Army during World War II, Chief Medical Officer in the Chemical Warfare Service.

DANIEL IMMERWAHR: Yeah and he goes on to have this illustrious career in medicine and basically suffers no consequences. But then, in the army in the Chemical Warfare Service, he gets another go.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Meaning he gets to use people as experimental animals again.

DANIEL IMMERWAHR: Exactly right. The United States government is seeking to develop chemical weapons in case World War II becomes a gas war, which it never really does. And overall some 60,000 people are tested on. And so sometimes that looks like having a mustard agent applied to your skin to see what kinds of blistering happen. Sometimes it's men are put in gas chambers with gas masks and are gassed to see how well their gas masks hold up. The large scale tests are these tests on this island that the United States seizes off of Panama.

[CLIP]

MALE CORRESPONDENT: After a survey of the Southwest Pacific Theater and the Caribbean area, San Jose Island and the [inaudible] was selected as the test ground. Since the climate and floor are similar to that which has been found in the Southwest Pacific. [END CLIP]

DANIEL IMMERWAHR: And it uses those to stage field tests. Large groups of men are asked to sort of stage mock battles and while they're doing this, planes fly over and gas them from the air. And then the question is how well did the men hold up?

BROOKE GLADSTONE: And where did these soldiers come from? Who are they?

DANIEL IMMERWAHR: The government is unwilling to send continental troops to be used as test subjects in San Jose Island in this way so Puerto Rican troops come. Many of them don't speak good English, they don't really understand what's happening. The men who were gassed, 60,000 men who were gassed, they experience long standing effects–many of them. Emphysema, scarring, lung damage. These men were also supposed to be doing this secretly and it only really came out in the 90s. Just how many of its own people and, you know, a good number of them Puerto Ricans, the United States had tested chemical weapons on.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: So Cornelius Rhoads becomes the head of the Sloan Kettering Institute and one of the forefathers of chemotherapy. This is a supremely surreal twist.

DANIEL IMMERWAHR: Some of the mustard agents that work as poison gases also work selectively in fighting certain kinds of cancers. And a number of doctors figured that out during the war, they put a pin in it and they say, 'after the war, let's check this out.' And so the government makes available its stock of surplus chemical weapons. Cornelius Rhoads is in charge of deciding which hospitals get it. He gives it to three hospitals and good bunch of it goes to his own hospital. And then he has a Sloan Kettering institute of which he's the head and then he has, for the rest of his career, this incredible chance. A hospital that is full of dying cancer patients who will submit to experimental treatments. And he just goes for it and just tests chemical after chemical after chemical and in doing so becomes one of the forefathers of chemotherapy.

[CLIP].

MALE CORRESPONDENT: Dr. Cornelius P. Rhoads of the Memorial Hospital in New York. [END CLIP]

DANIEL IMMERWAHR: He's on the cover of Time magazine able to cultivate this image of himself as a cancer fighter without anyone really acknowledging that he's had this back history in Puerto Rico.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Most people didn't know the informational segregation is so complete.

DANIEL IMMERWAHR: Yeah. After Rhoads dies, there is award that's given out by the American Association of Cancer Research in his honor for promising young cancer researchers. And this award is given for over 20 years before anyone who's involved, who's in the medical community and has a voice in that way, can say you might want to rethink the name of this award. Because powerful people in the United States, not just politicians, doctors too, have basically been able to think of their country as a contiguous blob and haven't really had to grapple with the parts of US history that have taken place in the territories.

[MUSIC UP & UNDER]

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Coming up, right understanding America's history of empire is vital for making sense of everything from bin Laden to The Beatles. This is On The Media.

**********************************

BROOKE GLADSTONE: This is On The Media, I'm Brooke Gladstone. We conclude our hour with historian Daniel Immerwahr by looking at the hidden ways empire has changed our history–and more importantly, for our purposes, our view of our history. Because that view enables us to look past human rights violations committed on our own soil. Today, we have military bases where American law doesn't apply.

[CLIP]

JIM MORAN: The reason we have Guantanamo is that this was set up to be above the law. It's extrajudicial. [END CLIP]

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Former Virginia Congressman Jim Moran.

[CLIP]

JIM MORAN: The rules don't apply. The rest of the world looks at this and it undermines our credibility and our security as a nation. [END CLIP]

BROOKE GLADSTONE: We have people born on American territory who aren't legally citizens.

[CLIP]

MALE CORRESPONDENT: The people of American Samoa are considered U.S. nationals.

MALE CORRESPONDENT: You're born owing allegiance to the United States but are not a citizen. America does have its allegiance back. [END CLIP]

And of course, this--.

[CLIP]

MALE CORRESPONDENT: President Trump tweeting, 'the people of Puerto Rico are great but the politicians are incompetent or corrupt. Their government can't do anything right. [END CLIP]

Even during the height of American empire, even during World War II, even among soldiers fighting in U.S. territories, there was confusion about what exactly the status of those territories was.

[CLIP]

MALE CORRESPONDENT: From the United States of America, Uncle Sam presents--[END CLIP].

BROOKE GLADSTONE: In your book, you recount the story of a young Filipino boy, Oscar, who encounters a G.I. coming down the street handing out cigarettes on Hershey bars. Speaking slowly, the G.I. asks the boy's name and when he replies easily in English. The soldier was startled and he said, 'how did you learn American?'

DANIEL IMMERWAHR: Yeah that story slays me because you have to think of it from the perspective of the soldier first. He's across the Pacific, he's been given maps, he's been told where to go, whom to shoot. He's arrived in the Philippines. He has seen some of the bloodiest fighting of the war and he meets this kid. And when the kid speaks in English he's totally confused why this kid should speak in English. When Oscar explains, 'oh the reason I speak English is that after the Philippines became a U.S. colony, you guys sent a bunch of teachers and we all learned to speak English.' The soldier just looks at him and says, 'oh I didn't realize that the Philippines was a U.S. colony.'

[MUSIC UP & UNDER]

DANIEL IMMERWAHR: He doesn't actually realize that he's fighting on U.S. soil.

[MUSIC UP & UNDER]

DANIEL IMMERWAHR: Usually think of the war as catapulting the United States into the position of global leadership with a larger military, a more bustling economy than anywhere else. Actually, the war did something else too. It gave the United States a lot of territory. So much territory that there were more people living in its colonies and occupied zones, like Japan, than were actually living in the States. If you looked up, at the end of 1945, and you saw a U.S. flag flying overhead it was more likely that you were living in a colony or occupied zone than you were actually living on the U.S. mainland.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Truman saying--.

[CLIP]

HARRY TRUMAN: We do not seek for ourselves, one inch of territory in any place in the world. [END CLIP]

BROOKE GLADSTONE: FDR said it. Everyone said it. But people are like we're going to keep Micronesia right? I mean suddenly our borders are malleable.

DANIEL IMMERWAHR: It's a moment when the United States has the ability to decide what its territorial destiny will be. It could take a lot of that territory. It could convert its occupations into annexations if it wanted to. And when Truman says the thing that so many past presidents had said, 'we covet no territory,' there is a scandal about that– the State Department complains, the military complains, the public complains. Are you really saying that we're going to give up all the land that we fought so hard to get. The places where we've planted our flag and they're particularly concerned about Micronesia, which is a sort of buffer zone between Japan and the western parts of the United States including Hawaii. That's where a lot of the bloody fighting in happens in World War II. And the idea of the United States surrendering the strategically valuable space, that's hard for a lot of people to continents. And in fact Truman amends his statement.

[CLIP]

HARRY TRUMAN: Outside the right to establish necessary bases for our own protection, we look for nothing. [END CLIP]

DANIEL IMMERWAHR: We're going to keep what we need to preserve our security. In that moment, right after World War II when the United States has so many options territorially, the end of World War II brings a worldwide revolt centered in Asia against Empire. Formerly colonized people have often seen their empires dislodged–often by Japan. They have access to arms. They've heard the idealistic speeches of FDR that this war is not a war for empire. This is a war for liberation. Which produces a sense of shame, which makes it a lot harder for powerful countries to insist that empire is right and proper. And that's just how civilization goes without fearing the kind of real on the ground and possibly violent resistance that they'll face in the colonies. The cost of colonialism has gone up.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: So that's one of the trends. The other one is that there are new ways to project power worldwide without controlling vast swathes of territory. A lot of these are technological. We can now produce a kind of nitrogen based fertiliser that replaces guano. We needed rubber and we developed fake rubber. We got plastic and then basically all we really needed were military bases.

DANIEL IMMERWAHR: That's exactly right. So on the one hand, the United States figures out how to generate synthetic substitutes for a lot of things that had formerly depended on colonies for– rubber is a really good example. At the start of the war, the United States has a rubber crisis.

[CLIP]

MALE CORRESPONDENT: We'll Charlie, this is one of the last rubber tracks we'll get.

MALE CORRESPONDENT: That's right.

MALE CORRESPONDENT: If we don't get rubber, we'll have to stop making good tanks. [END CLIP]

And the reason it has a rubber crisis is that Japan has seized a number of European and U.S. colonies in Southeast Asia in rich rubber growing lands. And it looks to a lot of people like the U.S. Economy is just going to fall flat on its face because you can't fight a war, it turns out, without rubber. What happens, and this is a surprise to a number of people who lived through this and are watching, it is that the United States figures out how to make rubber not from rubber plantations but from petroleum, from oil–of which it has a great deal. And so suddenly, it's done a sort of colonies for chemistry swap that allows it to no longer depend, for strategic reasons, on tropical colonies. Rubber's one example plastic which is also honed during the war replaces any number of tropical products and allows the United States to, sort of, be immune to the desire to colonize large places so that it can control for strategic reasons their economies.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: We got radio to facilitate communications.

DANIEL IMMERWAHR: It used to be the case that if you wanted to send a secure message from one part of the planet to another, you had to send it through a wire. And if you wanted that to be secure from sabotage, interruption or espionage, you had to control all of the territory along that wire. And So the British Empire was obsessed with getting a large telegraphic network that went only through British controlled territories. So its adversaries couldn't snip its cables or listen in. But the world of radio bring something different. With radio, you can just control one transceiver in one spot, another in another spot and beam the message from one to another. Now people can still listen in but if you get really good at encrypting your messages, you can solve that problem as well.

[CLIP].

MALE CORRESPONDENT: A roger six [inaudible] they're between hills, two, nine or a zero, three, two, six, south of the--[END CLIP]

DANIEL IMMERWAHR: A similar thing happens in transportation as you see a world that goes from surface hugging transportation, such as steam ships, cars, trucks and railroads, to a world where, ultimately, if you need to get something from point A to point B and you don't control the territory in between, you can transport it by plane. The United States gets really good at using plane and radio and it figures out that, ultimately, when push comes to shove, what it really needs is just a series of well situated points all across the planet.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: That's what you call a pointillist empire which still endures today.

DANIEL IMMERWAHR: Yeah. It's important to recognize that, although the United States has distanced itself from colonialism–it no longer has the Philippines, Hawaii and Alaska have become states, Puerto Rico underwent a constitutional change although it's still very much a U.S. territory–but from a strategic perspective that's not the core of the U.S. Empire today. What the United States has is hundreds of overseas bases. Places where it can land, places where it can detain people, places where it can repair and places where it can store weapons. And that is really the face of power today for the United States. If you took all U.S. overseas territory today and mashed it all together, you would have a land area that's less than the size of Connecticut. They may be small but, oh boy, are they important.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: A lot of history turns on those places and a lot of culture, a lot of Americans may not know this country's colonial history, but people in Puerto Rico do, people in the Philippines do. And so do people who live near those bases all over the world.

DANIEL IMMERWAHR: So one really good example is the city of Liverpool. Before World War II, it hadn't been a particularly culturally inventive city. And then after the war suddenly it lights up like a Christmas tree.

[MUSIC UP & UNDER]

DANIEL IMMERWAHR: And it's just band after band after band and, you know, hundreds of them and they're playing rock music.

[MUSIC UP & UNDER]

DANIEL IMMERWAHR: Suddenly, it's a sort of world center. And it's not all of Britain it's doing it. It's particularly the Liverpool.

[MUSIC UP & UNDER]

DANIEL IMMERWAHR: Liverpool has, right outside of it, the largest U.S. base and all of Europe. And as a result, Liverpool is the sort of borderlands between this outpost of the United States and, a still very much. Impoverished and war torn Europe. And young people from Liverpool and from the area, recognize that the men on the base are a great source of cash. And at the same time they're receiving records from them. They're getting musical instruments from them. So it's not an accident that The Beatles come from Liverpool. Liverpool is the sort of contact zone between the United States and Western Europe.

[MUSIC UP & UNDER]

BROOKE GLADSTONE: It isn't all sunny. In Japan, there's a deep sense of resentment. Riots every 10 years or so. Two Japanese ministers forced to resign because they deferred to the U.S. in matters related to the base. And then the Saudi Arabian bases, one could say that they had a role to play in 9/11.

DANIEL IMMERWAHR: That's right. Often in areas where bases are stationed, people are drawn into them because their sources of income, but they often find themselves resenting the bases–understandably. And you can see that so well in Saudi Arabia. So after the war, the United States establishes a military base in a place that had already been a sort of company town for a set of oil companies, Dhahran, and it has to build up this base. It draws on a lot of local laborers to do so. One guy who's been working on this space for a while is a Yemeni bricklayer named Mohammed and he's really good. And the people he's working for are very encouraging of him and he starts his own firm and starts to get a lot of contracts. The firm is called Mohammed and Abdullah sons of Allaud bin Laden. The guy who builds this base and who built some other U.S. bases is Osama bin Laden's father. And Osama bin Laden grows up around U.S. bases in the Middle East, U.S. sponsored construction projects in the Middle East. And on the one hand, he's part of this. That's where his money comes from. He gets really into construction. He's a construction guy. On the other hand, he gets deeply resentful and regards it as a form of imperialism. And it's this basing issue, particularly as the United States puts more troops in a formerly closed based in the 1990s, that sets Osama bin Laden on his jihad against the United States. It's the issue of U.S. troops being stationed in Saudi Arabia, the land of Mecca and Medina. Turning, as Osama bin Laden regards it, turning Saudi Arabia into a U.S. colony. That's his main source of complaint about the United States.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: How do we know that?

DANIEL IMMERWAHR: The first thing that we know Osama bin Laden did is a bombing at that base.

[CLIP]

BILL CLINTON: An explosion occurred this afternoon at the United States military housing complex near the Dhahran, Saudi Arabia. [CLIP UNDER]

DANIEL IMMERWAHR: Precisely the base that his father helped to build, and that bombing is timed so it is the eighth anniversary of the stationing of U.S. troops there. He's communicating through that date exactly the thing that he is protesting.

[CLIP]

BILL CLINTON: The explosion appears to be the work of terrorists. And if that is the case, like all Americans, I am outraged by it.

[MUSIC UP & UNDER]

BILL CLINTON: The cowards who committed this murderous act must not go unpunished. [END CLIP].

[MUSIC UP & UNDER]

DANIEL IMMERWAHR: I think that the United States has to get it right on empire. For too long, it's been so easy, from the mainland, to not think about the overseas parts of the United States despite the fact that mainlanders have been consistently affected by them. The overseas parts of the United States have, too often, been sacrifice zones. Places where the full cost is paid for decisions made in Washington. World War II in the Philippines, that's where most U.S. nationals died in World War II. And many of them die from the U.S. military itself, which bombs and shells its own cities as it's trying to dislodge the Japanese. My point is not that military strategy was wrong but my point is that it was made in a kind of bubble without any real reckoning of who it is that lives in the United States. And I think that can't keep going on.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Daniel, thank you so much.

DANIEL IMMERWAHR: Brooke, it's been a pleasure.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Daniel Immerwaher is a historian at Northwestern University and author of How to Hide an Empire: A History of the Greater United States.

[MUSIC UP & UNDER]

BROOKE GLADSTONE: That's it for this week's show. On The Media is produced by Alana Casanova-Burgess, Micah Loewinger. Jon Hanrahan and Asthaa Chaturvedi. Leah Feder, however, did the heavy lifting. We had more help from Xandra Ellin and Sherina Ong and our show was edited by me and Kat. Our technical director is Jennifer Monsen. Our engineers this week were Sam Bair and Josh Han. Big thanks to WNYC archivist and Andy Lanset. Katya Rogers is our executive producer. On The Media is a production of WNYC Studios. Bob Garfield will be back next week. I'm Brooke Gladstone.

UNDERWRITING: On The Media is supported by the Ford Foundation the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation and the listeners of WNYC Radio.