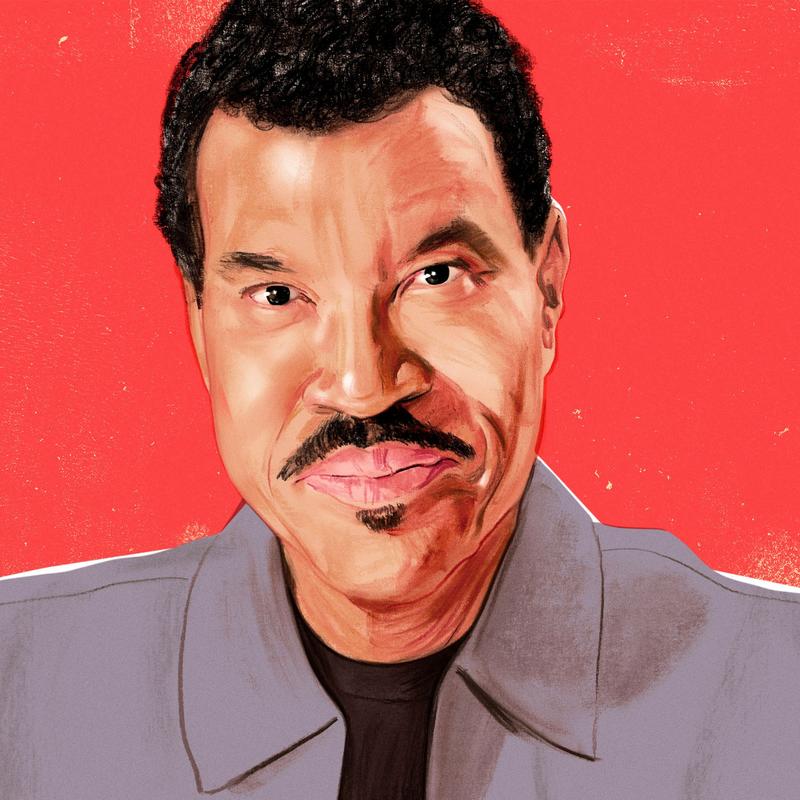

How Lionel Richie Mastered the Love Song

David Remnick: Lionel Richie has remained a star in the music scene long after many of his peers have faded away. Richie has been making music for 50 years. He's sold over 100 million albums, and he's endeared himself to younger generations as a judge on American Idol. His hits include Stuck on You, Say You, Say Me, Brick House, and the great duet with Diana Ross. Endless Love.

[MUSIC - Diana Ross and Lionel Richie: Endless Love]

David Remnick: Lionel Richie is now the author of a memoir. It's called Truly. While the book has a lot of triumphs to cover, Richie also writes frankly about his failed marriages and the breakup of the Commodores, the band that launched him into stardom. For Hanif Abdurraqib, a contributing writer for The New Yorker, speaking with Lionel Richie was also personal.

Hanif Abdurraqib: I wanted to open, perhaps by showing I'm a collector of vintage music shirts. I collect vintage music shirts and have my whole life, as my adult life. I think I found someone who maybe worked for the Commodore's road crew because they sold me all this stuff from the '81 tour.

David Remnick: No.

Hanif Abdurraqib: I got this '81 crew tour shirt, and on the back it says, "They make it rock, we make it roll."

[MUSIC - The Commodores: Zoom]

David Remnick: That is badass. Yes, I do. Oh, my God, man.

[MUSIC - The Commodores: Zoom]

David Remnick: Their conversation begins in a pivotal moment in Richie's career. 1977, and the release of the Commodores' ballad, Zoom.

Hanif Abdurraqib: I was interested in this in the book when you talked about Zoom. In the early stages of the book, you talked about Zoom being the work of a dreamer and someone who was idealistic about the world they were in. It made me curious about the way that songs came to you early in life, even before you maybe knew what they were or before you played at the piano with your grandmother. These kind of things.

Lionel Richie: Right. It's interesting because you never know. People have a chance to kind of define you, and you kind of fall in line with the story they have about you. I was this guy who was how they described me was I suffered from attention deficit, hyperactive. It's hard for him to pay attention. It's called ADD today. Back then, it was kind of, "How do you focus, Lionel?" I'm the kid who sat on the table, and my head is going like this in the classroom. The answer was, "Lionel, stop tapping on the desk. Lionel, would you like to join the rest of the class?"

It was at that moment that I didn't know that where I was was on the other side. That was the beginning of my young childhood years, when I kept thinking, "Why can't I pay attention to what the guy is saying in class. Why can't I pay attention to what's happening in church?" Because I was always daydreaming somewhere on the other side of this thing. As time went on, I started, if you will, listening more and more to the other side. As I got older, especially leading up to joining the Commodores, I started meeting people, meeting other great artists and other great writers, and realized, just sit there with them for a minute. Why is their leg tapping while we're having a conversation? Why is their head moving while we're having a conversation? You have the same problem that I had, or is that a problem? Or is that called creativity? You follow me?

Hanif Abdurraqib: Yes.

Lionel Richie: I had to kind of learn, and the word I'm going to use is discover. If I had to change the title of this whole book and just put it in realistic terms, it's how I discovered Lionel Richie, because it was from all of these moments of listening to myself and worrying, "Why can't I be like everybody else?" Listen, I know the answer to that, but I don't care about that. What I care about is it's more exciting what's on the other side that I'm listening to. You're a poet. You understand, when you start listening to that voice and trusting that voice now, you get to be stronger and stronger in your own right.

Up to Zoom, Zoom was that song that I was able to put in words what I really wanted to have as my mandate going forward.

[MUSIC - The Commodores: Zoom]

Hanif Abdurraqib: Early in the book, you say that you didn't begin to heal until you became a songwriter. I was interested if, through the making of this book, you uncovered new processes to heal or things that you were healing and didn't even know it.

Lionel Richie: You hit it dead on the head. When I started out this book, I had some great stories I was going to tell. Keep it real surfacey, no big deal. I didn't realize that it was going to take me on a journey, of it's not this mountaintop and this mountaintop and this mountaintop. It was this mountaintop and then the valley. The book is about the valley. Then, it got to the next mountaintop, and then to go to the next point, you have to go back down in the valley.

Well, each time I went down in the valley, it was painful, because there were things in this book that I wanted to forget in life. What created the real substance of me was I had to face my insecurities. I was not this jock that played football, basketball. I was not the hottest guy on the campus. I was not the yo, yo, ladies' man. I was the shyest kid in the world, man. Painfully shy to the point of just agony.

To realize and to discover that it was that that I had to uncover that actually made the book actually relatable. Because what makes a record a record, if you will, is when people walk up to me at the end of the song and go, "Lionel, I felt the same way." That means you had the same experience because all of us have doubts, and all of us are not sure. We have a great front. As time went on, I realized that what I was doing as a front, I had more substance in the back that I had to bring forward. You follow what I'm saying?

Hanif Abdurraqib: Yes, for sure. The book is so vulnerable. Also, you've seen that piece with your contradictions. From an early point in the book, you write about working at the bomb factory and being against the war, but also, there's that really beautiful scene early on, I think, physically being beat up by a bully. In a way, that made me think about how so often the memoir can be a place to stand atop the highest version of yourself, get atop the highest version of yourself's shoulders and shout about how great you are, particularly from a position where you have these accolades in this history. I was really moved by the way you were really still wrestling with yourself as the book went on.

Lionel Richie: What determines a man? What determines a person? I grew up in the '60s and '70s, where it's, "Stand up straight, son. Somebody will kick your ass, go back and kick their ass again." What the hell. No, it wasn't like that. The vulnerability of, "I don't want to kick anybody's ass." The joke of that bully, if you really want to know the truth about it, the bully showed up one night at a concert with his wife, and you could see he was angry to the point of-- Because his wife kept saying over and over again, "Oh, Lionel is so wonderful." I want to say, "I finally kicked the bully's ass."

What happens in all of this is that that was painful because they always had these lines where, if anything, you could talk your way out of something. This guy wanted to fight, no matter how I tried to avoid whatever was coming, it was coming. It was just something I had to deal with to the point of humiliation because you have to go home and face your father, and he goes, "Why don't you kick his ass?" and that's the end of the manly story.

I wrestle with that in my head because, as time goes on, the bully does not come to beat you up physically. The bully now becomes life, kicking your ass every day. Everybody has that bully sitting in front of them, and you have a choice of either saying, "I'm going to really tell you what I think about you," or just kind of tai chi you around a little bit till I get to the other side. Everything is not supposed to be that fight. Just get away from it or get over it, or win in some way.

I found that in my case, instead of trying to beat somebody from the standpoint of physical, I'll beat you here. Deal with what is it that you need? You need your ego. I'll give you your ego. What do you need? You need accolades? I'll give you accolades. What do you need? Once I satisfy that, then I just move away. Hopefully, if I do it correctly, I'll never see you again.

Hanif Abdurraqib: There's such generosity in the book. I thought about how richly the book was populated and how thoughtfully you wrote about other people and places. For example, there's that great-- You write so beautifully and tenderly about Tina Turner, and then you flow into writing about Marvin Gaye's loss. When I hit these points, and I thought about how your life has been filled with so many people from so many corners, how did you manage that balance of populating the book so well, but not turning fully away from yourself, still giving these people the love they deserve?

Lionel Richie: Well, you have to understand in life, if you find yourself saying, "And I thought, and I said, and I felt, and I did this, and I did that," okay, you're not being honest. How you got here was somebody else taught you something, somebody else passed something on to you that you decided, instead of giving them grace, you said, I. That's not important. This is my book, but I think it's important to say that there were aha moments in my life. I think I had a struggle. I think I was suffering. Okay, Talk to Tina Turner. I had Tina Turner for a whole tour. Two tours. The first tour, when she first left Ike, and the second tour, when we just toured together, and I saw a broken person, but I saw her crawl back up on that stage and walk out as the divine Ms. Turner. You understand me?

Hanif Abdurraqib: Yes.

Lionel Richie: Or you see Marvin, who was so misunderstood, who was such a-- You're talking about ADD or ADHD. He was just on another planet. You could see in his lifestyle, it was not going to serve him well. In his talent, he was so gifted, it was unbelievable. His lifestyle, the people he had around him, these are stories you have to look for a future singer like myself at that time, I had a chance to see it before I got in it.

With Marvin and with Smokey, you have a chance to hear somebody else's story. Then, you all of a sudden realize, okay, well, it's like my dad said, "You can either fall in every hole along the way of life, crawl out of that hole, and now you know that. Then you go to the next thing, you fall in the next hole, and you learn something. You get out. Or you can find out where all the holes are located and walk around them." In this case, by talking to Tina, by talking to Marvin, and these wonderful artists that have already been in it for years, it was just don't say much, just listen, and they'll teach you the whole navigation of this crazy world we're living in.

Hanif Abdurraqib: You have such a prolific catalog of songs that you've written, I mean, for others, too. It seems like the height of your form throughout your career has been the love song. Specifically, the love song, right?

Lionel Richie: Oh, yes.

Hanif Abdurraqib: I don't know if there are too many writers who do the thing you do well, where you are very up close and the love song is essentially like a dialogue, like a close dialogue between two parties, one of whom is the speaker and one of whom could be anyone. I'm wondering how you hone that. How you hone that sensibility, and also, if you, in the writing of this book, felt like you were the speaker speaking to yourself, trying to extract some tenderness from the process?

Lionel Richie: I now learned that when speaking to myself, that is how I speak to the public. That's how I present. I had to learn the most important note that I'll ever have to hit in my life. It's called the whisper. It's not hardcore. They have to hear this now. [takes breaths] [soft whisper] Now, oh, when you. Sometimes when I [breath] Follow that? All right. You don't scream, "I love you." You whisper, "I love you." You don't scream, "You hurt me." You really want to know you hurt somebody, they tell it to you very softly. "Hey, man, that was-- I'm devastated." That's soft. You have to get as close to the mic as you can. It's basically I'm whispering in the ear now. Now, it's not the big notes. It's the tenderness and the compassion that comes along with something in the silence with the whisper. Now, who did I learn that from? That's Marvin Gaye. Do you follow me?

Hanif Abdurraqib: Absolutely.

[MUSIC - Marvin Gaye: After The Dance]

Lionel Richie: Once you learn, it's not even the technique. It's believability. It's believability. That's the point that makes the difference between a song-- By the way, I did not plan this, that I was going to write these love songs. This is just what happened. I think I said it in the book, the reason I ended up with the love song is because five other guys came in with the funkiest songs in the world, so uptempo is not going to happen. You didn't discover that I could write uptempo songs until after I started doing solo because you can't win with five other guys bringing you all this uptempo stuff. I didn't try to go there.

How do I guarantee I get a song on the album? Here's the slow song. It was one of those things that I found that if you can just say something that's meaningful, like, for example, "When a man's in love, he's only got one story."

[MUSIC - Lionel Richie: Penny Lover]

Lionel Richie: That's all you needed. That's the takeaway. "I do love you, still." These are phrases that, I know, it didn't work out, and of course, in the anger of the divorce or in the anger of leaving, it's still, "Geez, I'm sorry. I'm sorry this got messed up like it did." Because you didn't start out not liking each other. There's a moment that you miss. That's what I tried to capture in these love songs.

Hanif Abdurraqib: It is captured in the book, too, this that what you just said, this sense of just because you fail at the end of the arc of love doesn't mean that the love was a failure. I thought you did that so well in talking about your own, which is, again, another vulnerable thing, talking about your own relationships and your own arc of love.

Lionel Richie: It's so important to-- I had to learn this because there's guilt in failure. What was I thinking? That was stupid. Or 20/20 hindsight. You can see it clearly, but at the time, there's something you have to remember: you're 30 years old. You're 25 years old. You're 35 years old, and you're 35 years old, experiencing something that is so amazing, it takes your focus off of what was supposed to be the important thing. I had never been to the Grammys. I had never been to the Oscars. I'd never been invited. You're realizing that you're growing daily.

All of a sudden, to go back and look at your life and say, "Oh, my God, man, I can't believe that this happened," or, "She said this, and I--" No, no, no, no, no. It was growth. The only reason I got to the next level was, unfortunately, I had experienced that, because when I first came to Hollywood, Commodores said it when we first came in, "We're never going to be like those other groups that break up. We're going to stay together and make sure we don't do that dumb ass shit that they always do." Well, the answer was, we did exactly what the rest of the groups did. Lionel Richie went solo, just like everybody else does. I kept thinking, "How did we fall into that trap?"

Then, all of a sudden, divorce. "Well, we're never going to have a divorce. God, we had that Beatles breakup that was crazy, we'll never let that happen." Or the Temptations. Oh, no. We did exactly what happened. In other words, it's the rite of passage. The reason that I ran into this wonderful problem in Tuskegee. I went to my minister, Father Jones, and I said, "I need counseling and divorce." He said, "I can't counsel you." I said, "Why?" He said, "No one in the church has ever divorced." Well, did you hear that? That means no one ever left Tuskegee to the point where they learned something else new, so their example of beauty is right there in their house. The challenges of their lives is right there in the house or on the campus of Tuskegee University.

Here I am going to another country every day at age 32, 37, 40. 42, are you kidding me? And trying to go back home and say, "Okay, everything is just like I left it. It's normal." It changed. I had to be kind to growth, and I had to be kind to my family for understanding that that was just if you listen to Wandering Stranger:

[MUSIC - Marvin Gaye: Wandering Stranger]

Lionel Richie: Please allow me to just go through these, and don't take it personally. It was something that happened, but I was growing.

[MUSIC - Marvin Gaye: Wandering Stranger]

Lionel Richie: You have to just kind of admit that to yourself, that it requires an apology if I want to say I'm sorry, but I had no control at the time. It was just it was happening.

Hanif Abdurraqib: Were you a different character in the Commodores than you were as a solo artist? Or was that solo character just an expansion and extension of the embodiment of who you became?

Lionel Richie: Oh, no, no. The solo guy was just a continuation, the actual experiment, the proving grounds, the experimental group, that was the Commodores. I remember they used to have a section at the bottom of each song. They said on the album, several vocalists. It was only two of us, me and Clyde, the drummer. What I would do is one track would be, "Oh, you know, I had some value, no purpose." All that. Then I'd come back with you, "Once, twice--" so they figured, that's two different people. Then the next person came along with, "Sail on down," so they got a country guy in there somewhere. No, no, that's a character. Whatever I would do, whenever I got ready to record, I would spend about 10 minutes trying to find what character I wanted to be.

Now, did it go forward? Yes, it did beause All Night Long was, "Well, my friends, the time has come--" Then, of course, on that same thing was Hello. Again, they now know that the several characters was just two of us, but I made it a point to make it interesting so it wouldn't sound the same. That's the thing. Your ear gets flat. "Okay, here comes the singer that sings in the same key, sings the same notes the same way." That gets boring after about four songs, five songs. Okay, so what's going to make it really different is, where's the character? When I discovered that, I realized we've got something now.

Hanif Abdurraqib: The last thing, and it's maybe a big thing. What I loved most about the book was its tone. You open with this scene, I think it's at Glastonbury, where you're-

Lionel Richie: Glastonbury. [chuckles] Yes.

Hanif Abdurraqib: "Can't believe I'm here." There's this beautiful tone of disbelief, and that actually maintains throughout the book. Even though it's a memoir and you are writing from the perspective of yourself, there are these moments where you sense that you're kind of like, "I can't believe this has been my life." You're steeped in gratitude. I'm wondering. You're still going, and I don't think you're going to quit or retire.

Lionel Richie: No.

Hanif Abdurraqib: Doesn't seem like retirement spirit.

Lionel Richie: No, no, no. It's not going to happen anytime soon.

Hanif Abdurraqib: You can hope. Do you kind of have these now when you are on American Idol, when you're mentoring younger artists, when you're watching the musical landscape change and you still have a heavy hand in it, do you get a chance to step back and consider your own legacy, or are you with a sense of disbelief, or are you kind of head down and keep the work going?

Lionel Richie: That was probably one of the most painful parts of the book, which is I always had the Italian race car driver's theory, which is, what's behind me doesn't count. What's coming next? What's in front of me? I had to turn around, look behind me, and evaluate behind me. For the couple of months I started, I didn't want to see behind me. I didn't want to dissect each phase of the low before the high, before the low, before the real low, before the high. In other words, I had to get through these things.

The book made me deal with my reality, which is, "Okay, I'm Lionel Richie, but I had to twist that to survive." I'll give you my ritual, I think it's in the book. Every morning I get up- it's true to this day- lying in that bed before I get out of bed, I've got a list of problems, I like to tell you. I've got a list of things. How are the kids? What's going on with the family? What's going on with the builder? What's going on this? Then I go struggle into the bathroom, and I look in the mirror, and I go, "Goddamn Lionel Richie." In other words, "What the hell?" Of all the faces that could be in that mirror, is Lionel Richie. Same guy I've been talking to for the last 76 years.

My point is, it becomes gratitude because this book is going to actually say to you what I had to go back and realize, I lived through that. It's not the winning, it's the losing. It's the pain. It's the struggle. Everybody keeps saying, "What kind of pain did you have, Lionel?" No, no, no, no, no, no. To get through loss. I lost a community of people. I lost Mom, Dad, Grandma, and that group. I lost the Commodores. I lost. I outgrew. I lost families.

To be here, it's emotional to realize that if I walk out and say, "And here I am, ladies and gentlemen," no, no, no, no, no. A lot of people crumble under just the loss of parents, or just the loss of kids, or just the loss of a divorce. I've seen strong people lose their complete minds over the fact that they couldn't deal with the loss of, but yet here I am to tell the story. I thought from the story standpoint, it would be very important to be open and to be real about how I felt vulnerable, not this confident writer, but, "Oh, my God, I wrote this song." You have to stop for a minute and go, "Hmm, I wrote this song." In the quiet of my life, I wrote this song. At the time I wrote it, it was, "I wrote this song." Looking back, it becomes, "Holy crap, I wrote that song."

Hanif Abdurraqib: That's beautiful. Lionel Richie, thank you for spending some of your time with me. The book is beautiful, and I thank you for your work, not just in the book, but the long career you've had, which has been immensely important to me. Thank you for your work.

Lionel Richie: Well, thank you so much. You've inspired me now to go out and go, "Yes, I did it."

[music]

David Remnick: Lionel Richie speaking with Hanif Abdurraqib from The New Yorker. Richie's new memoir is called Truly.

[music]

Copyright © 2025 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.