How a Gossip Blogger (almost) Became the Poster Child for First Amendment Rights

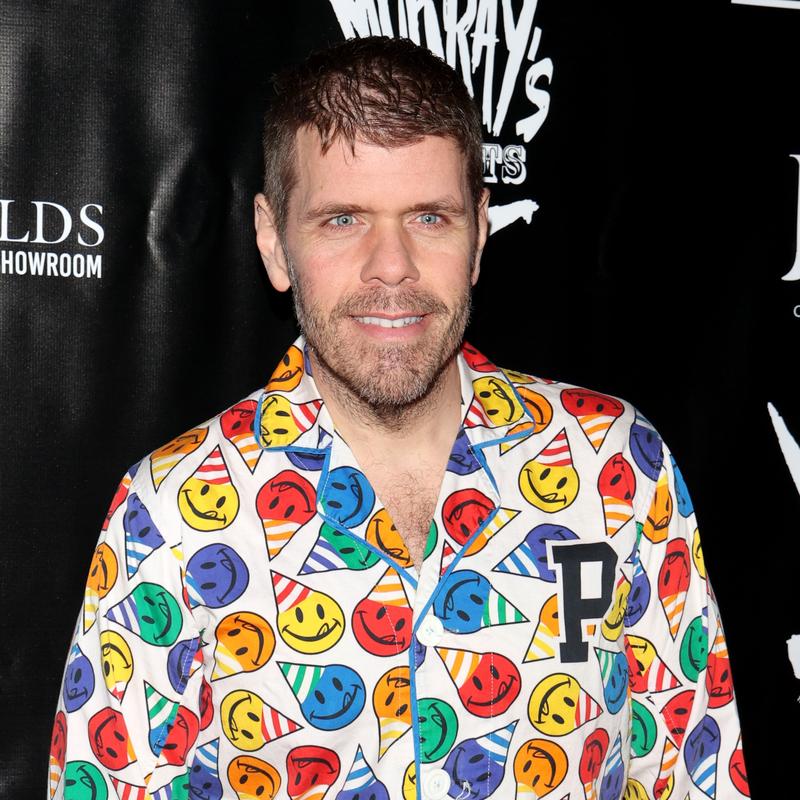

Micah: Hey, you're listening to the On the Media midweek podcast. I'm Micah Loewinger. This week, we're bringing you a story about a contentious legal battle at the edge of what can arguably be called journalism, a battle featuring two celebrities and a notorious gossip blogger, Perez Hilton. I first learned about this saga from a new piece about Hilton in the Columbia Journalism Review titled, The OG News Influencer. Its author, Joel Simon, is the founding director of the Journalism Protection Initiative at the Craig Newmark Graduate School of Journalism. Joel, welcome back to the show.

Joel: Micah, thanks so much for having me.

Micah: For listeners who don't spend a lot of time reading or thinking about entertainment news, who is Perez Hilton?

Joel: I don't want to present myself as the ultimate authority on Perez Hilton. In fact, I pretty safely ignored his career until I began to contemplate the possibility that he was involved in a legal matter that would have implications for press freedom. Perez Hilton is a blogger, social media personality, and a celebrity himself who, for 20 years, has chronicled celebrity culture in a variety of different media. He's done a lot of provocative things. He's been a bully.

He really went after Britney Spears when she was having mental health issues, and he seemed to really taunt and show a real lack of compassion. One of the things he's done that I think has been really controversial, especially for a gay man, is he's outed a number of celebrities, and the reality, of course, is all that leads to attention and clicks. That's part of his shtick. He's also been a consistent chronicler of the celebrity beat and the gossip beat, which, of course, is a historic part of journalism.

Micah: Perez Hilton has now become, according to you, an interesting and important edge case in the legal protections afforded to journalists. Five months ago, he received a subpoena from the legal team representing actor Blake Lively.

Perez Hilton: Hello, everybody. It is Perez, the queen of all media, the original influencer, and allegedly, I have been subpoenaed by Blake Lively.

Micah: What is Lively's team after exactly here?

Joel: Blake Lively is asserting in her legal claim that she experienced systematic sexual harassment on the set of the movie It Ends With Us and that when she tried to pursue this claim and raise her concerns about this behavior, she was subjected to a systematic smear campaign, which impacted her ability to defend her own rights. She alleges that this smear campaign was coordinated, and presumably that Perez Hilton was a part of it. They filed a subpoena. They wanted to see Hilton's notes and other documents to try and determine if this was true. It was a bit of a fishing expedition because they didn't seem to have a lot of evidence, at least that I saw.

Micah: What did his coverage look like? Because Blake Lively's team pointed to Hilton's commentary as evidence that he was either being paid for it or was in some way entangled with Baldoni in a deeper way. What kinds of things would he say about Blake Lively?

Joel: It's voluminous. There were so many posts and YouTube videos. What I would say is it had a lot of attitude. It was very critical, consistently critical. Just to give an example, he would consistently refer to her as Subpoena Serena after he was subpoenaed.

Micah: [laughs]

Joel: Also, there were a lot of people subpoenaed as part of the legal effort.

Micah: Serena was the character that Blake Lively played in Gossip Girl, arguably her most iconic role. Just as a taste, here's a video from last May.

Perez Hilton: Shameless and sham-tastic Blake Lively first started dating Ryan Reynolds in 2011. Stanky Blanky and Dick Pool got married in 2012, and ever since then, she has been very ambitious. Nothing wrong with that. I respect a hustler, but the sham poo company owner, see what I did there, has been trying to portray an image of who she is that does not align with the reality.

Micah: In addition to the mean nicknames, was he uncovering original information? Was there at least some journalistic aspect to this?

Joel: Absolutely. I think there was. He was getting alerts every time there was a legal filing, and he was going through those legal filings. It's sort of a niche audience that is following like every single development in this case, but he was often the first to get that information out there. He relied on the legal filings and then a network of sources that he had, who he didn't disclose to me, who were connected to the case, but definitely, there was new information. Absolutely.

Micah: Let's return to the legal jeopardy of all of this. How exactly did she go about pursuing Hilton, and what did her legal team accuse him of doing?

Joel: They didn't accuse Perez Hilton of anything because they're not pursuing Hilton legally. They're pursuing Justin Baldoni. They claimed that Hilton had information that was relevant to that legal action. The filing is in New York, and that's where the subpoena was issued for Hilton's notes and Hilton's reporting, but Hilton actually lives in Las Vegas, Nevada. That's where the subpoena was served, and that's where the legal drama played out.

Micah: Hilton, as you know, in your piece, has libel insurance, but he wasn't being sued for libel. He was being subpoenaed to have his reporting materials potentially enter into evidence and to maybe testify in court, so his insurance wasn't all that helpful. He ultimately couldn't pay the legal fees to defend against the subpoena. What did he do?

Joel: He did two things that lawyers will always, always, always advise people not to do, which was, one, he represented himself pro se, in other words, without a lawyer, and two, he had to produce legal briefs, so he just relied on ChatGPT to draft those legal briefs.

Micah: How did that go?

Joel: There's a reason that this is not considered a good practice. When he first did it, he told me that his original filing had a bunch of false citations in it.

Micah: It just hallucinated fake cases. [laughs]

Joel: Yes. It's kind of legal hallucinations. That was pretty embarrassing. That got called out. Afterwards, he said that he just started refining his process. He would triple-check everything, and he said that it got better and better, these filings. I'm going to say that I read the legal briefs, and I'm not a lawyer, I'm a journalist myself, but I didn't really initially realize that it had been written by ChatGPT. I've even talked to some lawyers who were surprised by this.

Micah: Let's talk a little bit about the historical precedent for these kinds of cases. Is there not a legal landscape that is supposed to protect journalists from getting sucked into lawsuits like this?

Joel: Yes and no. It really goes back to events from half a century ago, beginning in 1968, when Earl Caldwell, a journalist for The New York Times, was covering the Black Panthers in San Francisco. He received a federal subpoena for grand jury testimony and said that if I testify about my contacts with the Black Panthers, they're never going to talk to me again. My reporting will be undermined, and the First Amendment will be threatened. At the time, news organizations routinely complied with these sorts of subpoenas. The New York Times decided to contest the subpoena. Eventually, that Caldwell case was merged with another case, Paul Branzburg, a reporter from Ohio, and the case ended up before the Supreme Court in 1972.

Micah: The Supreme Court didn't ultimately side on Branzburg and Caldwell's side, right?

Joel: Correct. They actually lost the case. The test that The Times developed, they didn't assert that journalists should never have to comply with a subpoena, but they created a test that they thought would balance the public interest in having the testimony with the First Amendment protections for press freedom. They said that journalists should only have to testify if they had information that was relevant, material, and could not be obtained elsewhere.

They lost the case, 5 to 4, but in the dissent, the 4 dissenting justices kind of embraced that notion, that there should be a balancing test. That balancing test was later incorporated into state shield laws, which there was a whole movement to create these laws, and also into guidelines that was used by the Justice Department in evaluating whether or not to subpoena journalists. Journalists had some legal protections in law. There was also some jurisprudence that protected them, but the reality is that these protections vary tremendously from state to state because these are state shield laws.

In some states, journalists have what's called absolute protection. They never need to testify. In other states, they have qualified protection, so they might have to testify if their source is not confidential. There are so many definitions of who's a journalist and who is not a journalist. In some states, it has to do with who employs them and what kind of journalism they do and whether they have an institutional affiliation. In other states, it has more to do with the function that they perform, whether they're engaged in news gathering. Depending on where you live and the kind of journalism you do, you may or may not have shield law protections.

Micah: Prez Hilton lives in Nevada, where he was served. Nevada has really robust shield law protections. Blake Lively's team, meanwhile, filed the lawsuit in New York, which has weaker shield laws. How does that come into play?

Joel: The legal battle in Nevada was about whose law should apply. Hilton felt that if the Nevada law was applied, he would clearly qualify, and he would not have to testify. That's what he was asserting in his legal motions, but actually, he lost that argument. The judge ruled that New York state law was applicable, and so at the end of July, when the judge made this ruling, Hilton assumed that he was going to have to comply with a subpoena.

Micah: This is where the American Civil Liberties Union steps in. Why did the ACLU elect to represent Perez Hilton pro bono? What did they see in his case, you think?

Joel: There was a fan, I guess you could call her, who came to the hearing, and afterwards, she went to Hilton and said, "Hey, I know people at the ACLU. Maybe they would take up this case. Could I make an introduction?" That's what she did. Hilton had a meeting with Chris Paterson, who is the legal director at the ACLU of Nevada, and they decided to take him on as a client. I asked Paterson about why they did this. His point was that the ACLU generally sues governments and doesn't even get involved in civil cases, so this was already a departure.

What the ACLU was concerned about was that the government is basically asserting in all sorts of different contexts that people who are engaged in news gathering are not journalists, and they're not entitled to any sort of legal protections, and that if they could make the case with Hilton, broaden the definition of who's a journalist and who is entitled to these protections and these rights, then they could actually defend the rights of all sorts of people who are engaged in news gathering in more informal ways and not affiliated with the traditional or mainstream media, and that Hilton, because of the platform that he has, would get visibility for these issues. They saw this as an opportunity to make an important legal point that would have benefits to a significant number of Americans who do news gathering more informally, while also drawing attention to these issues.

Micah: I want to dig into that larger question in just a second. To tie up the Hilton thread here, there wasn't an opportunity to set a legal precedent here because Lively's team just dropped the whole thing?

Joel: Yes. When they called the Lively team to inform them that they were going to be representing Hilton, the Lively team informed them that they actually had been able to obtain the information they needed elsewhere and were withdrawing the subpoena.

Micah: What do you think was going on there? I don't really understand this.

Joel: There are a couple of explanations. What Hilton told me was that they didn't like the PR. They didn't like the optics of taking on the ACLU because they perceived themselves as the victim. I reached out for comment. I didn't get a comment, so I don't know if that's accurate. The other reality, of course, is when you're represented by the ACLU, you have some serious legal firepower on your side. Maybe they didn't really want to go up against that. The third option is that it's just a wild coincidence. They actually did obtain the information elsewhere, and they just happened to communicate that soon after the ACLU informed them that they would be representing Hilton. That's possible.

Micah: You said that the ACLU's interest in Perez Hilton and his case had to do with the question of who qualifies as a journalist and what qualifies as journalism in the eyes of the law at a time when journalism is rapidly evolving, thanks to social media and changes in the habits of news consumers. I understand this question also interested you. Tell me more about it.

Joel: That is the fundamental question that interested me. I don't really have a personal interest in Perez Hilton.

Micah: Don't worry, you've made that clear. [laughs]

Joel: Okay. I wasn't really paying attention to this, but I really think this is a critically important edge case with broad implications for press freedom. I go back to my career as the executive director of the Committee to Protect Journalists, and basically, my experience has been the same in every context, which is sometimes when I hear about these edge cases, I kind of resist and say, "That person is not a journalist, that person is not operating within the framework of journalism."

As I dig deeper, and I think about, "Who gets to decide that? Who gets to set the terms? Who gets to define where journalism ends and what rights are extended to people who exercise journalism informally?" I always come down on the side that we have to be generous with these rights and that we can't build institutional barriers that only protect certain kinds of journalism, especially at this moment when so much important journalism in this country and around the world is being done more informally.

That's not to say that I don't put tremendous value on journalism that's conducted within the ethical standards of our profession, with institutional support and resources. We obviously need that. We need that, and I'm going to defend that, but in terms of what actually constitutes journalism, it has always been an activity. The protections available to ensure that people can conduct this activity need to be extended as broadly as possible, and that's really what I saw was at play in this case.

Micah: Just give me some examples of compelling work being done by non-traditional journalists.

Joel: I'm going to give you some examples of journalists who are under threat for doing precisely this kind of work. One example I'd like to point to is Mario Guevara. He was a live streamer from El Salvador, but he was an immigrant in the United States. He had a background as a journalist, but his career in the US was focused on documenting and often live-streaming the activities of US immigration enforcement, and he was arrested while covering immigration enforcement action in Atlanta.

After he was arrested, he was put into deportation proceedings and deported to El Salvador, where he is today. Let's not forget somebody like Darnella Frazier, who was the eyewitness who documented the murder of George Floyd, and that video transformed history in a way. That was a fundamentally journalistic activity, and there's so much of that happening in so many different contexts. That's really what this case is about, in my view.

Micah: The legal framework that you're advocating for here would also apply to news content creators, journalists, and influencers, and people who make news for social media. Do I have that right?

Joel: Yes, I think you get a mixed bag. When you extend protections to a broader segment, you're going to get some people who are doing critically important work that has social value, and you're going to get some people who are doing work that has less social value and may even be harmful. That's free speech for you.

Micah: Of course. I do, though, want you to respond to what I've noticed is a segment of our listenership who, I guess, finds it frustrating when we call news content creators journalists. There are some who believe that that title should be guarded, that it should have a certain standards for ethics and practices, and shouldn't be thrown around too loosely. What do you think about that?

Joel: There's some news content creators who are doing outstanding work of social value and deserve recognition, and there are some people who are doing crap who should be criticized. In terms of the legal framework, I think that we make those distinctions as people who consume this information, but creating a sort of framework in which judges and legislatures are making those distinctions in this current climate could have unintended consequences.

You have to remember that the legal framework that defends the rights of journalists was really created half a century ago by general counsels working for major news organizations, and they represented those organizations. Their fundamental role was to protect the interests of the organizations that employed them, and I think the legal environment that we have today reflects that reality.

Just to give another example, I did a research project and published a report on how the police should respond when they, for example, issue curfews or dispersal orders when there are protests. Who gets to stay on the scene? Because we want journalists on the scene to document those activities. They were asserting in some context, unless you had a press badge and you work for a major news organization, then you didn't have the right to stay on the scene.

As I looked at that more carefully, I thought they're denying the ability of the American public to observe and understand their activities because the reality is the people who are there documenting are not always working for major news organizations. We really need to have a functional understanding of what constitutes journalism and extend those protections to people engaged in the news-gathering process.

Micah: In your mind, what is the most salient argument against opening up the definition of journalists to be as expansive as possible?

Joel: I'm very sympathetic to the other side. This is not an easy question. The most salient argument is that journalists have fought long and hard to create a legal framework that provides important and critical protections for journalists engaged in their work. If we expand those protections to everyone, pretty soon we might have them for no one. We might undermine the basic legal framework that allows journalists, in some circumstances, with an institutional affiliation, to operate with greater legal protections. There is a significant risk here. I don't deny that.

Micah: Just to return to the Perez Hilton of it all, I'm sure there's some people listening who really just don't find him particularly sympathetic. Just respond to that and explain why you're so keen to defend his protections and those like him in the eyes of the law.

Joel: We have Don Lemon doing kind of informal videos. We have Pulitzer Prize-winning journalists who are doing substacks. The whole way in which journalism is conducted is changing, and we need to evolve to address this reality. If that means that a certain number of journalists who maybe don't practice the profession with the highest ethical standards also receive some level of legal protection, so be it. That is a trade-off I am willing to make.

[MUSIC - Song by Booker T. & the M.G.'s: Slim Jenkins’ Place]

Micah: Joel, thank you very much.

Joel: Thank you, Micah.

Micah: Joel Simon is the founding director of the Journalism Protection Initiative at the Craig Newmark Graduate School of Journalism. That's it for the midweek podcast. Close listeners will have noticed a new name in the credits, Travis Mannin, our video producer, who's already started helping us expand our reach on TikTok and Instagram. Go over there and follow us if you don't already. Thanks for listening. I'm Micah Loewinger.

Copyright © 2025 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.