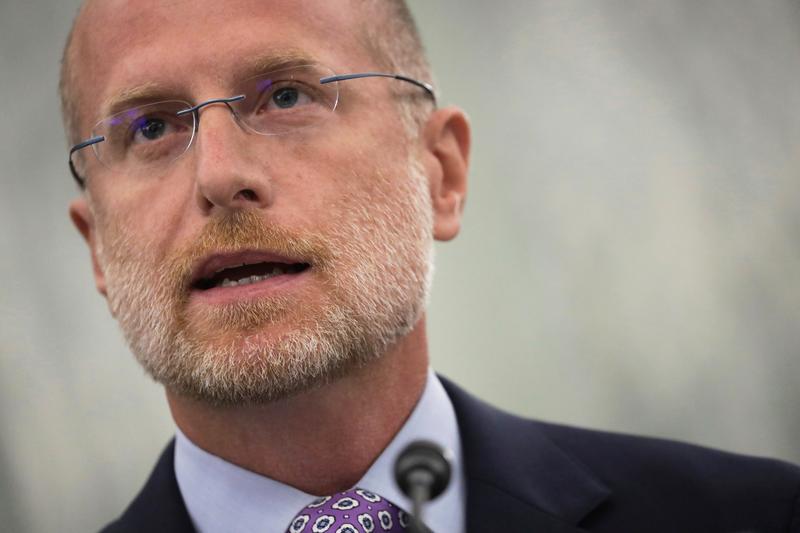

Brendan Carr’s F.C.C. Has Been Busy. Plus, Rewriting the History of Watergate.

Brendan Carr: We have to work together to smash the censorship cartel.

Brooke Gladstone: The new chairman of the FCC is putting the squeeze on news outlets. From WNYC in New York, this is On the Media. I'm Brooke Gladstone.

Micah Loewinger: I'm Micah Loewinger. Also on this week's show, there's a reason that some on the right want to reshape our collective memory of Watergate.

Michael Koncewicz: The idea that a clear majority of the country could be so repulsed by a president's authoritarianism. Let's make sure that never comes back again.

Brooke Gladstone: Plus, for Bryan Stevenson, the Trump administration's targeting of the Smithsonian for "improper ideology" makes the case for confronting America's darkest legacies.

Bryan Stevenson: I'm not interested in talking about these things because I want to punish America. I want to liberate us. There's thriving democracy waiting for us, but we can't get there if we don't have the courage to be honest about the things that have held us back.

Micah Loewinger: It's all coming up after this. From WNYC in New York, this is On the Media. I'm Micah Loewinger.

Brooke Gladstone: I'm Brooke Gladstone. On Tuesday, amid remembrances of Pope Francis and Earth Day celebrations, the dramatic resignation of a guy named Bill Owens still managed to make the news for good reason.

Reporter: This is huge news, and I mean, this literally shook the media news world today.

Reporter: The executive producer of CBS News' 60 Minutes, calling it quits today.

Reporter: He had been with the News program for 24 years, 37 years at CBS.

Reporter: Now, normally, that would probably not be news that we would bring you, except the circumstances rise to the level of, well, alarm. Owen said in a letter to his staff that, "Over the past months, it has become clear that I would not be allowed to run the show as I have always run it, to make independent decisions based on what was right for 60 Minutes, right for the audience." The context here is key.

Brooke Gladstone: 60 Minutes is facing a $20 billion lawsuit from President Trump and an FCC investigation into "intentional news distortion." The context the network's owner wants to expand, which the FCC could obstruct. It's just one in a series of intimidations, investigations launched or revived under the FCC's new chairman, Brendan Carr. Just a quick note here. WNYC, our producing station, is also under investigation by the FCC, along with a bunch of other public TV and radio stations. Next week marks Carr's firs100 days as chairman. He's been busy.

Max Tani: Brendan Carr has sent letters to both Comcast and Disney saying that he would be looking into whether or not their diversity hiring initiatives violated rules around fair hiring.

Brooke Gladstone: Max Tani is Semafor's media editor. He filled me in on what Brendan Carr's been up to.

Max Tani: The DEI hiring practices were part of what Brendan Carr laid out in Project 2025.

Brooke Gladstone: Has he actually done anything on this stuff?

Max Tani: He's just said that he's going to. That's another thing that is really important to keep in mind here. Brendan Carr has sent a lot of signals via Twitter, sent a lot of very threatening legal letters. He hasn't actually done much other than reopen investigations.

Brooke Gladstone: As I mentioned, he's also looking into PBS and NPR, including some NPR member stations, ours among them. It's the nature of non-commercial public sponsorship messages that Carr is using as his lever. He's concerned that some of them might be commercials, but actually they're underwriting. There are distinctions about what is and isn't allowed in public radio's sponsorship mentions.

Max Tani: From talking to people at NPR, I feel that I can say this confidently. There is a view that this is part of a larger effort by the Trump administration to cut federal funding for public media.

Brooke Gladstone: I don't think that's much of a stretch, Max.

Max Tani: Obviously, the FCC has to operate within certain regulatory framework. The focus of this complaint is not the ideological position that Carr and other Republicans have, which is that the federal government shouldn't be paying to fund public radio. Their complaint is about, "Oh, well, you actually violated some of the rules around sponsorships, and these sponsorships are actually ads." NPR believes that it's done nothing wrong here.

Brooke Gladstone: Onto the attacks on the networks. During the election, CBS aired an interview with Kamala Harris that Trump claimed was unfairly edited to, I don't know, make her sound smart. Subsequently, the conservative legal group called the Center for American Rights, that's Carr, filed an FCC complaint calling for an investigation into CBS. It didn't go anywhere, but Brendan Carr revived this complaint along with complaints of bias against ABC and NBC, which were also earlier dismissed. What do we know about the complaints against ABC and NBC?

Max Tani: The complaint that's been reopened into ABC is the result of what some on the right see as unfair moderation in favor of Kamala Harris during one presidential debate between Harris and Trump. The complaint against NBC is essentially a fair time complaint.

Brooke Gladstone: I love this one.

Max Tani: Yes. Kamala Harris appeared on Saturday Night Live, right in the weeks before the election.

Maya Rudolph: It's nice to see you, Kamala. It is nice to see you, Kamala. I'm just here to remind you, you got this.

Max Tani: That made Donald Trump very upset. He complained about it, said he wasn't being given equal time. The former FCC commissioner under Biden, Jessica Rosenworcel, dismissed the complaint at the end of her term, saying that NBC had made available equivalent time for Trump during other events.

Brooke Gladstone: This week, we learned that Bill Owens is stepping down as executive producer of CBS's 60 Minutes. That has to do with what seemed like a capitulation because Shari Redstone, who is the ultimate boss, wants to do a merger.

Max Tani: Yes, basically what we have found from talking to people within CBS and Paramount is that in recent weeks, as Paramount, the parent company of CBS, is trying to do a merger with Skydance, an entertainment company, that deal has not closed pending some FCC regulation. President Donald Trump has taken a strong interest in the editorial direction of 60 Minutes. Just earlier this month, he complained about segments that the broadcaster ran on Ukraine and Greenland.

Reporter: On Truth Social, he writes, "CBS is out of control at levels never seen before, and they should pay a big price for this."

Reporter: They should lose their license, he said.

Reporter: Hopefully, the federal chairman, Brendan Carr, will impose the maximum fines and punishment for their unlawful and illegal behavior.

Max Tani: The result of that was quite a lot of anxiety within Paramount, which is desperate for this deal to close. What we've reported is that Shari Redstone and Paramount was very interested to know the remaining segments that 60 Minutes was going to be running on Trump for the rest of the season, which ends in the middle of May.

Brooke Gladstone: We journalists don't like having the suits telling us what we can and what we can't report.

Max Tani: Shari Redstone's actually been increasingly public in her criticism of 60 Minutes. In early January, she appointed Susan Zirinsky, the former head of CBS News, to act as a standards editor. Zirinsky has been looking over many of the more controversial and sensitive segments that have aired on CBS.

Brooke Gladstone: Now, in terms of the editing of the Kamala Harris interview, they decided they'd go ahead and turn over the full transcript. Nobody found anything wrong with it?

Max Tani: That's right. CBS and Paramount made an unusual decision to turn over the unedited transcript to the FCC. They did take an additional step to release this publicly. We see from the transcript, they just took a different part of the same answer to clarify a statement from Harris, which was a little bit unclear. You would teach this in journalism school, essentially, run the most clear answer that gets closest to what the subject is trying to say.

Brooke Gladstone: I can't tell you how many times in editing I have dropped the first sentence of a guest's answer. That's generally the thumb sucking, time filling moment where they're thinking.

Max Tani: I'm sure you'll do that for this interview, and I think the audience will thank you for it.

Brooke Gladstone: Carr is still going with it, or is it just to put pressure on Shari Redstone?

Max Tani: He's left it open. It does beg the question of what exactly you're investigating. If the transcript is out there, everyone can judge for themselves whether the news has been distorted.

Brooke Gladstone: With regard to the complaint against CBS, Carr did invoke the news distortion policy, which is very rarely used. You have to provide evidence that the broadcast entity actually intended malice.

Max Tani: One of the things that I've done over the past few days is look at when has this been used before. There have only been a handful of complaints in recent years around news distortion, and generally, they have not resulted in investigations. Even the ones that have resulted in investigations haven't often resulted in fines. It is very, very unusual for the FCC commissioner to be getting involved in the editorial decisions of broadcasters. One of the things that I think is really interesting here is the balance that Brendan Carr is trying to strike. He's talked a lot about the desire for deregulation in the broadcast space, the desire for the government to get out of making some of those decisions.

Brooke Gladstone: Wow.

Max Tani: Yes. You've recognized the irony that at the same time, he also has been one of the most active commissioners of the FCC in recent memory.

Brendan Carr: One of my top priorities is trying to smash this censorship cartel. A lot of censorship that these companies are doing on their own, you also have secondarily pressure, particularly the last couple of years from the Biden administration to censor. Also, you've got this cohort of advertising and marketing agencies that are sort of the tip of the spear to enforce.

Brooke Gladstone: If the impact of all of this is fundamentally to strike fear, Bill Owens' departure from CBS seems like a sign that it's already having a chilling effect. Where else is the temperature dropping because of Carr?

Max Tani: He's also opened up an inquiry into Audacy, the radio broadcaster. He pointed to a broadcast on one of their California AM stations earlier this year, a Hispanic radio station that was essentially letting listeners know that there were local ICE raids that were happening in the area. He said that that violated regulations and that he would be looking into it. We should note as well that Carr had singled out Soros-funded media before even becoming the FCC chair. Audacy is owned by Soros Fund Management and is a large public broadcaster. That's one place that we haven't mentioned yet. That is certainly seeing additional federal scrutiny.

Brooke Gladstone: For the last year and a half, Truth Social has relentlessly pursued a defamation case against 19 media companies that flubbed a story about the platform's earnings, said that it had lost more money than it had actually lost. Among his targets was the media company Nexstar, which owns a lot of stations and also the Washington political newsletter The Hill. It settled even though a lot of people said they had a really good case.

Max Tani: Nexstar, which is a large owner of local broadcasters, has been lobbying the Trump administration and the FCC to lift the ownership cap on local stations. Right now, there is a regulation in place that limits the amount of stations that can be owned by one company. We reported earlier this month that Nexstar actually, in late 2023, reached a settlement with Truth Social to fire one of its reporters in exchange for Truth Social dropping a defamation lawsuit. This reporter's job was essentially to rewrite news from other organizations.

They were assigned the story from the Hollywood Reporter and just wrote it up. Under most circumstances, this would be seen as slightly sloppy. It was obviously a pretty strong signal that Nexstar was willing to make some compromises. It should be noted that they were the media company that was dropped from this suit. Since Trump has returned to office, The Hill has said that it's going to make some changes. They've said that they're going to get rid of their DEI reporter, one of their immigration reporters, one of the reporters on climate change and the environment. It does seem like part of a very, very deliberate strategy to send signals to the Trump administration that they don't want to be perceived as too far to the left.

Brooke Gladstone: The fact that The Hill is dropping all those beats says an awful lot. I wonder what you think the public needs to know about the nature and severity of these pressures on journalists. I mean, so much is in chaos. How high should this issue rank on our anxiety list? Below threats to Medicaid, but above, say, renaming the Gulf of Mexico? I mean, this is the question about stakes.

Max Tani: You see, over the last four years, Trump and allies of Trump have really thought hard about the levers that they could pull, the pressure that they could put on media organizations. You're seeing that play out across broadcast news in particular. The people that lose in this case are the news consumers who do suffer if an organization decides that they're so scared of federal government regulation that they're just going to hold back, not go as far as they might go, or decide to scrap something altogether.

Brooke Gladstone: AJ Liebling often observed that news is fundamentally a business. There are good parts to that. That way, the government can't control it. If the business gets too big, then it runs into the government all over again. Its future comes down to rich people talking to other rich people, and the regular people who they serve really don't get a vote.

Max Tani: Yes, and you really do see that in these big multifaceted corporations that make a lot more money from other parts of the business, whether that is something like theme parks or Internet.

Brooke Gladstone: Or they just want to grow, grow, grow.

Max Tani: Exactly. You definitely see over the last several months that news concerns and pursuing the most aggressive journalism possible is taking a back seat.

Brooke Gladstone: At just the wrong time, I think.

Max Tani: As a journalist, obviously, my bias is in favor of aggressive and fair reporting. Any situation in which that's impeded obviously is deeply concerning to me.

Brooke Gladstone: Thank you so much.

Max Tani: Brooke, thank you.

Brooke Gladstone: Max Tani is the media editor at Semafor and co-host of the podcast Mixed Signals. Right after we recorded this interview, the Wall Street Journal broke the news that Paramount is in talks with the FCC to make concessions over their DEI initiatives.

Micah Loewinger: Coming up. Turns out it's never too late to rewrite history.

Brooke Gladstone: This is On the Media. This is On the Media. I'm Brooke Gladstone.

Micah Loewinger: I'm Micah Loewinger. Everything old is new again in America now and always.

Joe Rogan: I go back to what I learned about the Woodward, Bernstein, Nixon thing at Watergate. That was all essentially an intelligence operation. Have you ever looked into that?

Micah Loewinger: This is podcaster Joe Rogan in an episode of his show released this week.

Joe Rogan: They tried to get Nixon out of there, the most popular president in the history of the country in terms of the vote, and they were successful.

Micah Loewinger: Rogan made the same claim last month during his interview with actor Bill Murray.

Joe Rogan: Like it was a complete intelligence operation. Nixon definitely did the things they accused him of, but the whole thing was coordinated by the intelligence agents to get Nixon out of office.

Micah Loewinger: That Rogan has repeated this conspiracy theory three times on his show is a coup for the decades-long movement to rewrite the history of Watergate and rehabilitate the 37th president.

Jim Byron: We're still learning a lot about Watergate. Particularly over the last couple of years. There's been a number of new revelations regarding the Watergate special prosecutor's files.

Micah Loewinger: This is a 2024 C-SPAN interview with Jim Byron, who has since been appointed to a senior archivist role at the National Archives by Donald Trump.

Jim Byron: The story of Watergate isn't over. It remains endlessly fascinating. I think that what it's revealing is there is this great thirst for a fuller understanding of President Nixon.

Micah Loewinger: Byron, who is not a historian, was the president and CEO of the Nixon Foundation and its library, one of 16 presidential libraries administered by the National Archives. It only joined the nonpartisan national archives system in 2007, at which point a fight broke out around how the Nixon Foundation had been presenting the history of Watergate to the public.

Michael Koncewicz: Many observers noticed that even by the standards of presidential libraries, the tone was aggressively partisan.

Micah Loewinger: Historian Michael Koncewicz wrote an article for Time.com about this effort to rescue Nixon's legacy.

Michael Koncewicz: There were lines that were critical of Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein, the reporters who uncovered Watergate. There were lines that attacked John F. Kennedy and Robert F. Kennedy. The tone was more aggressive, and that's because it was a private library. That changes in 2007, under the leadership of then director John Taylor. This was a close aide to Richard Nixon in the 1980s and '90s. He strikes a deal with the National Archives to join the Federal Presidential Library System.

Micah Loewinger: You were working there, right? You witnessed some of the tension between these two institutions firsthand.

Michael Koncewicz: I did. I started working at the Nixon Library in 2010. Our staff was trying their hardest to create a new exhibit about Watergate, to explain the Watergate scandal and Richard Nixon's resignation in a textbook way. That was a struggle because the Nixon Foundation changed their leadership during this time and got rid of the individual who made the deal with the National Archives. In their places were people who were much more protective of Richard Nixon's legacy.

They pressured the National Archives to not support this exhibit. Fortunately for our staff, the exhibit went up in 2011, and it's still there to this day. The fact that it was such a long process speaks to the fact that the Nixon Foundation and their supporters did not agree that Watergate was a settled subject. They saw it as a battle in their campaign to rehabilitate Richard Nixon's legacy.

Micah Loewinger: That battle over the historical memory of Watergate and Richard Nixon is very much still alive. In mid-February, Trump declared on Truth Social that the president of the Nixon Foundation, Jim Byron, would act as senior advisor to Marco Rubio, the current acting archivist at the National Archives and Records Administration. This seems to be a big win for the pro-Nixon camp. They're basically running our nation's archives at this point. Why is this bigger than just a battle between historians?

Michael Koncewicz: We can break this up into two parts. What's at stake is, for one, an attempt to weaken the National Archives' ability to frame history in a nonpartisan way to the American people. If you cannot agree on the standard story of Watergate, then what can you agree to? That's why this battle matters so much. Richard Nixon, still to this day, his approval ratings are fairly low. There was a Gallup poll, I believe, in 2023, I think he was around 32%, 33%. He's still generally seen as an unpopular president.

What has changed, though, is Richard Nixon's crimes were seen as exceptional 50 years ago, and those crimes are not seen as nearly exceptional as they once were. Richard Nixon's crimes are instead seen by an increasing number of American people, conservative or otherwise, as run-of-the-mill politics.

Micah Loewinger: In the years immediately following his resignation, most conservatives didn't want to touch Nixon with a ten-foot pole. There were a few outspoken voices that tried to clear up his legacy. What were they saying, and were they getting any traction at the time?

Michael Koncewicz: They were enthusiastic supporters of Richard Nixon. I mean, Pat Buchanan was one of Richard Nixon's top speechwriters. G. Gordon Liddy went to prison for the 37th President of the United States.

Micah Loewinger: Because he was one of the organizers of Watergate himself.

Michael Koncewicz: Yes, G. Gordon Liddy was in the lookout building across the street from the Watergate Hotel. He's part of the plumber's unit. He nevertheless, though, sees Richard Nixon as a martyr for the conservative movement that was trying to counter the social movements of the New Left. Movements for racial justice, for gender equality. Pat Buchanan, in many ways, Watergate reinforced his views about just how important of a figure Richard Nixon was for the conservative movement. This is true of other conservatives. M. Stan Evans, longtime conservative activist, told the journalist/historian Rick perlstein in the mid 2000s, "I never liked Richard Nixon until Watergate."

Micah Loewinger: Huh?

Michael Koncewicz: Reading the Watergate transcripts actually made him more of a fan. Prior to that, he saw Nixon as this complicated ideological figure who conservatives could not trust because his domestic record, and to a certain extent even his foreign policy record, did not follow conservative values. When he read the Watergate transcripts, he liked the fact that Nixon hated the New Left so much, that Nixon's dark side was so much a part of his personality.

I think for several decades, it's fair to assume that was true of many other conservatives who kept those views secret. What's happened in the last decade is with the rise of Donald Trump, a lot of those conservatives have come out of the closet as Nixon supporters, or they themselves have rediscovered Nixon and realized that, "Hey, this is the president that we should focus on," not Ronald Reagan, Richard Nixon. As Christopher Rufo says, Richard Nixon is the model for counterrevolution.

Micah Loewinger: What about Donald Trump? What do we know about his views on the 37th president?

Michael Koncewicz: The two actually met each other in New York in the 1980s. They had some mutual friends. People like Roger Stone, Roy Cohn. Nixon and Trump had several encounters. There is even a letter that Donald Trump framed from Richard Nixon where Nixon said, "You have a future career in politics if you want it." Donald Trump kept that letter and framed it in his office. What I think is more important is the people who Trump surrounds himself with. That suggests that he is at least willing to take Watergate revisionism quite seriously. Roger Stone, longtime close advisor to Donald Trump. He has a small museum of Nixon memorabilia. He has a tattoo of the 37th President on his back.

Micah Loewinger: A giant tattoo.

Michael Koncewicz: Yes, yes, yes. The symbolism isn't exactly subtle here.

Micah Loewinger: In 2019, he even mentioned Richard Nixon's legacy when he was asked about not firing Robert Mueller.

Donald Trump: I learned a lot from Richard Nixon. Don't fire people.

Michael Koncewicz: He did not always follow that advice, but I think it's interesting that he mentioned that during a pivotal moment during his first term.

Micah Loewinger: Here is JD Vance with a bit of foreshadowing, speaking at the National Conservative Conference in 2021. This is how he ended his speech.

JD Vance: There was a wisdom in what Richard Nixon said approximately 40, 50 years ago. He said, and I quote, "The professors are the enemy."

Michael Koncewicz: The quote he includes in his speech comes from the Nixon White House tapes.

Richard Nixon: Press is the enemy. The professors are the enemy.

Michael Koncewicz: This was a source of shame even among Nixon supporters for many decades. Now, JD Vance is bragging about this conversation and speaking about it favorably to a crowd of national conservatives.

Micah Loewinger: Tell me about some of the other narratives that conservatives have been pushing about Nixon and Watergate. You mentioned Christopher Rufo before. How has he been talking about Nixon?

Michael Koncewicz: In the summer of 2023, Christopher Rufo puts out a 10-minute video on his website.

Christopher Rufo: Although Nixon failed to realize his ambitions during his presidency, he still holds the key to understanding America's ongoing cultural revolution and how to defeat it.

Michael Koncewicz: Rufo is telling his fans that if you are uncomfortable with today's left, then you need to look to Richard Nixon for inspiration.

Micah Loewinger: In that video, Rufo pointed to Nixon's use of law enforcement to go after political dissidents. He refers to Nixon's so-called counterrevolution against the New Deal and Great Society government programs, basically anything in government that could be associated with progressivism. Ultimately, he argues, Nixon wasn't some disgraced leader who chose to resign in scandal, but rather that he was the target of a deep state conspiracy.

Christopher Rufo: Harper's editor Jim Hogan, former Nixon aide Geoff Shepard, and other researchers have uncovered tens of thousands of declassified documents that reveal the black hand of the state as a prime mover in Nixon's demise.

Michael Koncewicz: Yes, what these figures often neglect to even acknowledge is that Richard Nixon committed crimes. We have taped evidence. We also have tons of evidence to show that Richard Nixon repeatedly tried to use the IRS for political purposes. He targeted hundreds and hundreds of individuals whose only crime was opposing Richard Nixon's presidency. None of these Watergate revisionists will ever fully acknowledge the evidence that is easily accessible to the American people that prove that Richard Nixon was guilty of a crime.

Micah Loewinger: Tucker Carlson, former Fox News host. He's in this Richard Nixon revisionist movement. Tell me about his role in all of this.

Michael Koncewicz: Tucker Carlson seems to start caring about Nixon and Watergate around 2017, 2018, in the middle of the Mueller investigation into Donald Trump and Russia. In 2018, Carlson visits the Nixon Library. He speaks in their replica of the East Room, and he tells the crowd--

Tucker Carlson: I have never been here. I was just stunned by what I'd missed about the Nixon--

Michael Koncewicz: Later on, when he loses his show on Fox News and he starts a new show on X, he actually brings on Geoff Shepard, one of the most well-known Watergate revisionists. He's gone as far to say that the CIA was out to get Richard Nixon. He apparently has even convinced Joe Rogan of this.

Joe Rogan: Why did they want to get rid of Nixon?

Tucker Carlson: First of all, we don't need to know motive to know what happened.

Michael Koncewicz: They, meaning unelected federal employees, got rid of Richard Nixon, which is the most anti democratic way to make a leadership change that there is.

Micah Loewinger: Back to today, all of these people, Christopher Rufo, Tucker Carlson, the people at the National Archives, why are they trying to rewrite the history of Watergate? What is the modern-day political use in changing how Americans think about this moment in the '70s?

Michael Koncewicz: The idea that a clear majority of the country could be so repulsed by a president's authoritarianism. Well, let's try to throw that out the window. Let's make sure that never comes back again. If they can poke enough holes in the standard story of Watergate or the American public's understanding of Richard Nixon, if they can get casual consumers of history to understand that, "Hey, maybe Nixon wasn't as bad as you thought he was." Then what that will do is make it far harder for another Watergate to ever happen again.

Micah Loewinger: There are so many storylines to keep track of, so many attacks on federal agencies and parts of our government that we've long taken for granted. What's your pitch to listeners for why they should be paying attention to what's happening at the National Archives? Why does it matter?

Michael Koncewicz: If we can't document our own history, particularly the history of presidential crimes, then almost anything could be manipulated. If we can't trust the federal government to handle these basic facts of US history, then what can we trust them with?

Micah Loewinger: Michael, thank you very much.

Michael Koncewicz: Thank you, Micah.

Micah Loewinger: Michael Koncewicz is a political historian and the associate director of New York University's Institute for Public Knowledge.

Brooke Gladstone: Coming up, yes, there is hope for restoring and preserving the whole American story.

Micah Loewinger: This is On the Media. This is On the Media. I'm Micah Loewinger.

Brooke Gladstone: I'm Brooke Gladstone. Last month, President Trump ambushed the world's largest museum complex with his executive order titled Restoring Truth and Sanity to American History.

Reporter: Part of the executive order reads, "Over the past decade, Americans have witnessed a concerted and widespread effort to rewrite our nation's history, replacing objective facts with a distorted narrative driven by ideology rather than truth."

Reporter: President Trump fires a broadside at one of America's leading cultural institutions, the Smithsonian, saying wants to deny funding for what he calls improper ideology.

Brooke Gladstone: The executive order also lambasts an ongoing exhibit about race and sculpture at the Smithsonian American Art Museum for observing that societies, including ours, "Have used race to establish and maintain systems of power, privilege, and disenfranchisement." That, "Race is a human invention." Just a little over a week after that order--

Reporter: The National Park Service has removed a reference to Harriet Tubman from a webpage about the Underground Railroad. Several references to enslaved people and the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 are also gone.

Brooke Gladstone: This is all part of the administration's effort to root out what it calls improper ideology. What do these assaults on our museums and memorials imply for our collective understanding of history, especially the darkest parts of our history?

Bryan Stevenson: There's no ideology in documenting the history of slavery or lynching, or segregation.

Brooke Gladstone: Bryan Stevenson is a public interest lawyer and founder of the Equal Justice Initiative, a human rights organization based in Montgomery, Alabama. Later, he led the creation of the Legacy Museum and the National Memorial for Peace and Justice, and the Freedom Monument Sculpture Park, all of which commemorate our nation's history of slavery and racism. What we've seen of the standards of the White House, these institutions would indeed be deemed improper. I asked him what he thought of the whole idea.

Bryan Stevenson: If I present to you the laws that codified racial hierarchy in many parts of this country, they created a racial order that existed for a very long time. You cannot understand the achievement of the Tuskegee Airmen or Jackie Robinson if you don't understand this history.

Brooke Gladstone: What about this history is he so afraid of?

Bryan Stevenson: I don't think it's just the president. We've never fully addressed the legacy of slavery. Never. The African American History Museum and Culture in Washington, that was the target of some of these orders, didn't exist until 2015. We're in the early days of trying to create an honest record. We opened our national memorial in 2018. It was the first time there was a comprehensive memorial in this country about the history of racial violence and lynching.

For many Americans who grew up with no conversation, nothing in the cultural landscape, this is new. It's just we're now getting to a full account of this history. It's not ideological. It's not intended to be disruptive. I'm not interested in talking about these things because I want to punish America. I want to liberate us. I actually think there's something that feels more like the thriving democracy that we seek waiting for us. We can't get there if we don't have the courage to be honest about the things that have held us back.

Brooke Gladstone: Trump's order claims that the Smithsonian's rewrite of history, he calls it, deepens societal divides and fosters a sense of national shame. Conservatists often use national shame as a cudgel. "What about the children? If they learn about our racist past, they'll hate themselves." Maybe they just don't believe that slavery actually left that legacy you referred to, the inability to amass generational wealth because of housing redlining, or bars to higher education. I mean, Trump's first big lawsuit in the '70s, a loser of a case he was forced to settle, involved keeping Black renters out of his father's apartment blocks.

Bryan Stevenson: We have a 9/11 memorial in this country. We built it almost immediately after the tragedy of that day.

Brooke Gladstone: We were the victim then. We weren't the perpetrators.

Bryan Stevenson: Hear me out. What I'm trying to say is that we saw value in acknowledging the suffering that people experienced in this country on the day of that tragedy. Now, we're not good in this country of memorializing the things that we have done wrong, but it doesn't mean that we don't believe that memorialization is important. I think that's an important distinction to make, because if we believe it's important for ourselves, then we have to believe that it's important for us to do when we're on the other side of mistake. We haven't applied it historically because we haven't had to.

Brooke Gladstone: I think that Trump and the Heritage Foundation that created Project 2025, they all believe very strongly in the power of monuments and in the power of history, which is why they're working so hard to extirpate those memorials to parts of history that they would prefer we don't remember. I know from having spoken to you before that when you were developing your own museums, which powerfully present our history of slavery and racism and the continuing impact, you drew inspiration from how the memory of the horrors of the Holocaust was preserved, not just in curricula, but on the streets of Berlin. Nowadays, however, plenty of people in an increasingly right-leaning Germany have started to grouse. They don't like it at all.

Bryan Stevenson: I don't think we should think that memorialization will save us from all of the challenges that are created when you're in an era governed by the politics of fear and anger. When people allow themselves to be governed by fear and anger, they start to tolerate things they wouldn't otherwise tolerate. They start to accept things they wouldn't otherwise accept. How far you will go, how much pain and suffering you will create, is dependent on how much you still know and understand.

If you know and understand that there was a Holocaust in Germany, then maybe there will be some constraints on what happens in that country that, honestly, we don't have in this country, because we haven't done that same reckoning. It's not a guarantee, but there's a consciousness about the harm of that history, that even those people are careful, many of them, to not be completely identified by that era.

Brooke Gladstone: According to Nate Freeman, writing in Vanity Fair, the Smithsonian is firewalled from changing administrations because Congress appoints the Smithsonian's governing regents, who can serve years, sometimes decades. It's got some insulation. Legally, it might be harder for Trump to have his way, at least with the Smithsonian. Then again, Congress. How successful is he likely to be?

Bryan Stevenson: There will be tremendous resistance on institutionalizing narratives that are false or that are incomplete. We've seen that already. Immediately, when this order went out about what DEI is and the hysteria around DEI, a base in Texas said, "Oh, we can't talk about the Tuskegee Airmen because they were Black air pilots who did extraordinary things in the first half of the 20th century. We can't show a film about the first women who were pilots because they thought that was advancing DEI."

Brooke Gladstone: Anything that doesn't involve white men.

Bryan Stevenson: Yes, but people quickly reacted to that. There was an effort to take Jackie Robinson's history off of a website. People want the symbols of achievement and freedom, but they don't want the story that makes these achievements so meaningful. I think there will be tremendous resistance. That doesn't mean that it won't happen. Which then means that we have got to create institutions in this country that allow that truth-telling to take place.

Brooke Gladstone: You told me years ago when I visited your then-new museum that you saw, as a child, the integration of the schools, and you thought, "Wow, the way to justice is through the courts." You won multiple landmark cases at the Supreme Court to say, expand the rights of condemned prisoners. You worked tirelessly to fund the Equal Justice Initiative, and you created all of these landmarks and memorials. What do Trump's actions mean in connection with the work that you have been doing all these years to reinforce our collective memory of the worst horrors our country has ever committed? Has it made you rethink your approach in any way?

Bryan Stevenson: No, not at all. If anything, it's reinforced it. I still believe in the rule of law and began my career focusing on using the courts to expand rights for the most disfavored people in our society. We would not have been able to shield the intellectually disabled from execution if we didn't have a court committed to human rights. I realized 15 years ago that we were going to have to get outside the courts and begin this narrative work to move forward, that we were going to have to commit to truth-telling because the environment outside the court was causing retreat inside the court, and we see that today.

People used to say, "Why are you spending time on a museum and a memorial, on a sculpture park, when there's so much need for legal work?" I said, it's because we have to create this outside environment. I've learned from history, the civil rights movement didn't succeed just through activism on the streets. There were lawyers in the courts winning these decisions, but those lawyers didn't win by themselves. There were people engaged in storytelling and narrative work that helped to create that moment. We're in a moment like that today. I never used to talk about my enslaved great grandparents, never, never acknowledged that my people came from Caroline County, Virginia.

Brooke Gladstone: You didn't?

Bryan Stevenson: Not in the first.

Brooke Gladstone: When did you?

Bryan Stevenson: I started probably about 10 or 15 years ago. It's only when I'd gotten in my 40s that I began to appreciate that lineage. Nobody in my family had gone to college. There were people near me that had outhouses and no functioning septic systems. I always thought of that as something that held me back or that was shameful in some ways. As I got older, I began to appreciate all that they had given me. My great-grandfather learned to read, even though it was against the law in Virginia in the 1850s for an enslaved person to learn to read.

He risked his life to learn to read because he had a hope of freedom. In the 1850s, he didn't know that a civil war was coming a decade later. He used that hope to develop that skill. After emancipation, my grandmother said, he would read to formerly enslaved people who didn't know how to read. Once a week, he'd read the whole newspaper to them so they would know what was going on. My grandmother, she was a reader, and she insisted that her children be readers and her grandchildren be readers. My grandmother would greet me sometimes when I went to her house with a stack of books. I'd have to read something before she let me into the house.

My mom went into debt when we were children to buy us the World Book Encyclopedia because she knew we didn't see hope outside the door, where there was so much poverty and despair. We could read about it in those books. I owe the enslaved who learned to love in the midst of agony. I owe the terrorized and the trauma. I owe the segregated and the disfavored for the justice that we are still seeking more than to give in to an executive order. I'm disheartened by some of what I see, but I am in no ways dissuaded.

Brooke Gladstone: You gave a speech at Monticello earlier this month for Thomas Jefferson's 282nd birthday, in which you said, it's easy to lose hope right now, but hopelessness is the enemy of justice. In my lifetime, we've never been in such a period of retrenchment. There's always two steps forward, one step back. This is just a great leap backwards. What are you hopeful for, specifically? Where do you draw that hope from?

Bryan Stevenson: I don't know that I agree that we've never seen this before. Listen, in the 1960s, after we passed the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965, there was nothing but resistance.

Brooke Gladstone: Yes. The world didn't change on a dime. There were great leaps forward legally before they became entrenched societally. Now we're seeing those things being uprooted. Argue with me. Tell me I'm wrong.

Bryan Stevenson: I think you are. At the end of the Civil War, 4 million Black people were emancipated. There was a moment where we believed we were going to have this new, beautiful America. Those 4 million enslaved people chose reconciliation to build a better America. For a short period of time, they voted. They built churches and schools. Then it all collapsed. The US Supreme Court preferred states' rights over the constitutional rights guaranteed by the 14th Amendment of equal protection or the 15th Amendment.

They were disenfranchised for a century. When you think about the glory and the hope of emancipation and the collapse of all of that, and then this era of terror, violence that would force millions of Black people to leave lands that they own, it was a period of greater retrenchment than what we are seeing now. Then, after decades of struggling to stop that lynching violence, Black soldiers went to France during World War I. They went to Europe during World War II. They fought courageously. They came back in their uniforms, and they were targeted for lynching.

Then, after passing these civil rights laws in the 1960s, we saw the formation of a new system of control characterized by mass incarceration. We became the nation with the highest rate of incarceration in the world. It didn't happen until 2000 that 1 in 3 Black male babies born in this country became expected to go to jail or prison. I don't think it's true that we haven't had to deal with retrenchment and reaction to forward progress.

Brooke Gladstone: I stand corrected.

Bryan Stevenson: The reason why I am hopeful is because what we're now seeing is the formation of a new narrative struggle. When you're enslaved, you have to focus on freedom. When you're being terrorized and lynched, you have to focus on security. When you're disenfranchised and you don't have any opportunities for education and other businesses, you have to focus on civil rights. Now we're at a moment where we are in the beginnings of a narrative struggle. The reason why I'm hopeful is that earlier, even in my career, we didn't have thousands of committed journalists and professionals and storytellers and filmmakers and writers who could participate in this narrative structure.

We have never been better situated to win the next phase of this struggle toward a just America than we are right now. While I'm worried, I just can't accept that this is unprecedented. In fact, without some of the optics of 2020, these narratives wouldn't be resonating. It took seeing Black people and white people out on the streets protesting against police violence, seeing people coming together, corporations committing millions of dollars to support racial justice and equity, saying Black lives matter. It took that to trigger the counter-narrative that we're seeing now. Without that step forward, we wouldn't see this backstep now.

Brooke Gladstone: Amidst all of these attacks on the federal agencies that protect our health, that protect human rights, that uphold constitutional protections, and so much more, you refuse to despair.

Bryan Stevenson: Yes, those institutions are being assaulted, but I don't think this battle is over. I really don't. I hope that if the government-funded institutions no longer become places where you can get an honest history, that people will support the private institutions that will take that up. I boldly claim that we didn't take a penny of state or federal funding in creating our sites.

Brooke Gladstone: It's remarkable given how gorgeous it is.

Bryan Stevenson: Thank you. The truth is we were never offered a penny of state or federal funding. We've had over 2 million people come to our sites, many of them skeptically.

Brooke Gladstone: How do you know?

Bryan Stevenson: Because they tell us. They'll say, I didn't want to come, but now I'm totally aware of things I didn't understand. We see extraordinary things come out of that. Beautiful things. We have a collection of 800 jars of soil in our museum. We collect these soils from lynching sites. People who are involved in erecting markers collect the soil, put it in a jar that has the name of the victim, the date of the victim, and then they bring it back to the museum.

An older Black woman was digging soil at a site in west Alabama. She was afraid because it was on a dirt road in the middle of nowhere. As she was about to dig, a big white man in a pickup truck drove by and stared at her. It made her anxious. Then he drove by again and stared some more. Then he parked his truck, got out, and walked toward her. She was terrified. Then the man asked, "What are you doing?" She was going to tell him that she was just getting dirt for her garden. Then she said, "Mr. Stevenson, something got ahold of me. I told that man, I'm digging soil here because this is where a Black man was lynched in 1937." She just looked down and started digging.

The man surprised her by asking, "Does that memo you have talk about the lynching?" She said, "It does." Then he asked, "Can I read it?" He started reading while she started digging. After he finished reading the memo, he said, "Would it be all right if I helped you?" She said, "Yes." The man got down on his knees, and she offered him the implement to dig the soil. He said, "No, no, no, no, no, you keep that. I'll just use my hands." She said he started picking up the soil and putting it in the jar, and throwing his hand into the soil. She said there was something about the conviction with which he was putting his whole body into this that moved her.

She went from fear to relief to joy so quickly she couldn't help it. Tears were running down her face. The man turned to her and he said, "Oh, ma'am, I'm so sorry I'm upsetting you." She said, "No, no, no. You're blessing me." They kept digging, and they were getting near to filling the jar. She looked over at the man, and she noticed that he had slowed down. His face had turned red. Then she saw that there was a tear running down his face. She reached over and put her hand on his shoulder. She said, "Are you all right?" That's when the man turned her, and he said, "No, ma'am." He said, "I'm just so worried that it might have been my grandfather who helped lynch this man."

She said they both sat on that roadside and wept. She said, I'm going to go back and put this jar of soil in the museum in Montgomery. Then the man said, "Ma'am, would it be all right if I just followed you back?" She said, "Sure." She called me on the way back. She said, "Mr. Stevenson, I want you to come to the museum and meet my new friend." I was there when these two people who met on a roadside in a place of pain and agony and violence and bigotry came in and together did something beautiful by putting that jar of soil in that exhibit.

I'm not naive. I don't believe that beautiful things like that always happen when we tell the truth. I do believe that we deny ourselves the beauty of justice when we refuse to tell the truth. I've seen too much beauty come out of truth-telling, too much restoration, too much redemption, to believe that truth-telling doesn't have a power that is greater than the fear and anger that is prompting these orders, prompting some of this retreat. I worry about people who are already surrendering and waving white flags, and running for cover. I just don't think that's the way we're going to get to the other side.

Brooke Gladstone: Bryan, thank you so much.

Bryan Stevenson: My pleasure.

Brooke Gladstone: Bryan Stevenson is a public interest lawyer and the founder and executive director of the Equal Justice Initiative, a human rights organization in Montgomery, Alabama.

Micah Loewinger: That's it for this week's show. On the Media is produced by Molly Rosen, Rebecca Clark-Callender, and Candice Wang.

Brooke Gladstone: Our technical director is Jennifer Munson, with engineering help from Jared Paul and Owen Kaplan. Eloise Blondiau is our senior producer, and our executive producer is Katya Rogers. On the Media is a production of WNYC Studios. I'm Brooke Gladstone.

Micah Loewinger: I'm Micah Loewinger.

Copyright © 2025 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.