Mar 9, 2012

I've been reading Daniel Kahneman's phenomenal Thinking Fast and Slow, and it has been blowing my mind. Not just a little--huge, messy chunks of my brain are splattered on the wall. Metaphorically, of course.

Kahneman has a large, audacious brain (he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Economics, if you need some evidence beyond my lavish praise), and he's spent decades thinking about how it works. He writes poignantly about his longtime collaboration with Amos Tversky and the great joy of their work together before Tversky's death in 1996 (which left Kahneman to collect the Nobel without his intellectual partner).

Over the years that Kahneman and Tversky worked together, they were fascinated by the errors that our minds make...errors that we leap to...that come easily and quickly to us. They would hatch up tests that illustrated this, with statistically significant, demonstrable results. I can imagine the film version--a montage scene starting in an Israeli cafe at noon. Time would whiz by as a tea cup stood out against the backdrop of dusk, then night. Then, smash cut to the test subjects walking into the university, the test proctor nodding, and Kahneman and Tversky behind a glass watching it all.

Kahneman starts his book by praising the mind that works intuitively. We see a photo of an angry person, and immediately we understand this information. Right? It's not a drawn-out process of conscious data collection and decision-making. You do not think, "the lines surrounding the mouth are at angles, what does that indicate? Wait--look at the eyes and nose, are there any clues there?" Rather, it's a single, immediate understanding: this person is livid. Our mind can access large pools of knowledge this way, by seamlessly integrating small, almost imperceptible data points. The abilities that work in this way - fast - are considered in a single category: "System 1." And System 1's power feels magical. Kahneman writes that it's the "hero of the story." It's the creative brain, the associative thinker. But, Kahneman warns, it's also got its weaknesses. System 1 has biases, and messes up dramatically. Frequently. It doesn't like to work hard, and it doesn't do well under duress. And, it can't be shut off to let System 2 do its thing in peace.

Meet System 2. It does the math. It can reason out tough problems, it can handle statistical thinking. But System 2 requires time and attention. Credit for the articulation of this two system scheme goes to Keith Stanovich and Richard West, and Kahneman marvels at the genius of this operating system...writing that the division of labor is brilliantly efficient, that it "minimizes effort and optimize[s] performance."

But sometimes these systems clash, and ensnare us in dangerous mental traps.

A Few Examples

1. Which line is longer?

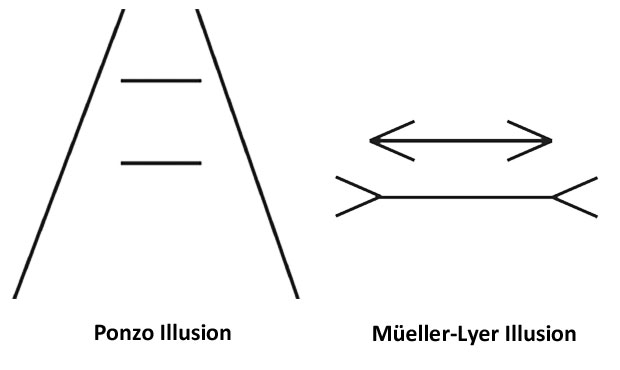

Look at the two illustrations above. Each shows two horizontal lines stacked on top of each other. In each picture, which horizontal line is longer? Top or bottom? If you know this one, your systems are aligned in their rapid response. If not, you might have had System 1 say: "Same length!" and System 2 say "Wait! Let's measure." (Or, System 1 might have noted the word "illusion" and quickly provided the answer: it's a trick!)

2. How many widgets?

This test was devised by Shane Frederick:

"If it takes 5 machines 5 minutes to make 5 widgets, how many minutes does it take 100 machines to make 100 widgets?"

Did your System 1 brain blurt out an answer? If it happened quickly, it's probably wrong. If you haven't seen this before, your system 2 brain needs to puzzle it out. (The correct answer is at the bottom of the post.)

3. A bat and a ball cost $1.10

The bat costs $1.00 more than the ball. How much does the ball cost? (Scroll to the end for the answer.)

Just like in example 2, to get this right takes a bit of attentive thought. And that's how you know the System 2 brain is working.

Systems in Cahoots

System 2 is the skeptical and diligent editor to System 1. System 2 is the CFO, asking the hard questions and demanding evidence. It's a powerful counterpoint to System 1's leaps. But System 2 is also fallible. It has a tendency to believe System 1, and even become to its accomplice...by supplying evidence for System 1's quick conclusions.

One thing both systems of my brain appreciate is that Kahneman's book is littered with examples of fascinating studies. He references many that have fascinated us at Radiolab...the fruit and cake experiment, hot and cold coffee, the marshmallows... The skeptical mind loves all the supportive documentation. But then, the self-aware skeptical mind wonders if it's just that the evidence in the studies lets the lazy System 1 mind feel confident about the results--even when System 2 hadn't quite totally understood the information which was cited (as my tired brain sometimes didn't).

I think part of why this book is blowing my mind is that I've been reading it in the infrequent (and short), precious moments after my toddler falls asleep, before I'm too tired to read anymore. She's 2 1/2 now and is a marvel of language acquisition. Every day she surprises me with the new words she's using. A couple of days ago, she asked what the smear on the car window was. "Oh, that's bird poop," I told her. "Bird poop?" she repeated, and stared at the window. The next day, I still hadn't managed to find time to wash the car, and my daughter surprised me: "Open my backpack and get me the wipes and I want to clean the window for you. I am gonna make you so happy." I didn't know she knew the word "window," and I didn't know she could conjugate her verbs like that. It's amazing what she observes and assimilates and recalls.

My daughter has a limitless appetite for books about counting and the alphabet. And I love to think that I'm helping to make her a strong thinker, by making those immediate associations strong. Memorization isn't so much working analysis as instinct. But you need to have a full catalog of associations, a brain that plays and understands, to have a mind that calculates well and is skeptical about the right things. I also think about how the stop-and-think training of System 2 is my job as a parent. I have to teach her to apply system 2: "Wait--look both ways before you cross." A kid is all raw energy and instinct at that age and it takes practice to learn how to be diligent and intentionally attentive and rigorous. And like Daniel Kahneman, I am marveling at how the brain works...how efficient it is, how magical when the two systems collaborate perfectly. How satisfying it is to see instinct supported by effort. Or, as Steve from Blue's Clues says (hey! quiet down there, my "what-have-I-become" self-loathing brain system...it's a valid reference!), "Cause when we use our mind, take a step at a time, We can do anything...that we wanna do."

Answers:

Example 2: 100 minutes 5 minutes! (Thanks everybody, for catching our error. Go System 2!)

Example 3: 5 cents