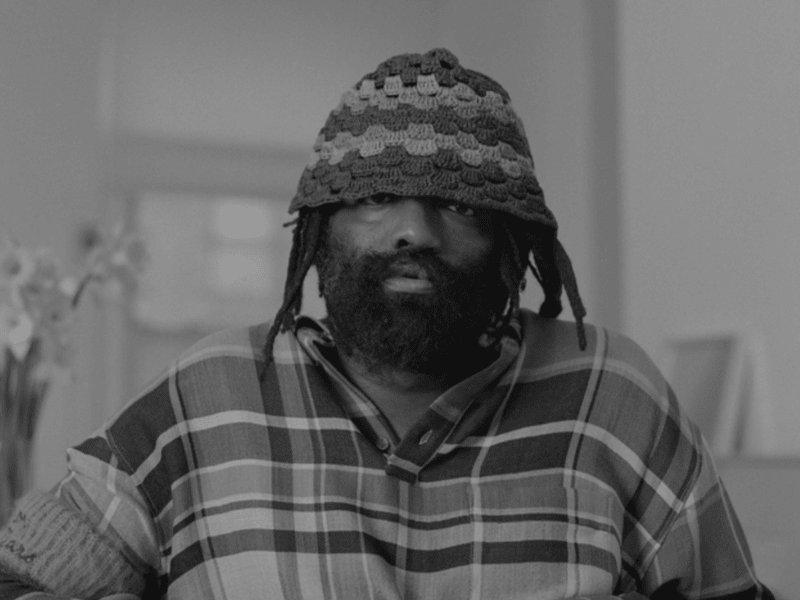

Designer Tremaine Emory on Validation in Consumer Culture

( Katsu Naito )

Tremaine Emory: The hardest thing feels like to make a brand cool, relevant, and meaningful in this space. That feels like an almost impossible challenge. That's what I want to do. When my store opens, you're going to see kids of all colors waiting online. Something that's got a story. Even if they're not wearing it because they care about their story, there's still a billboard for that story.

And I think that's me leaving the game different than when they came in.

Helga: I'm Helga Davis, and welcome to my show of fearless conversations that reveal the extraordinary in all of us. My guest today is the visionary fashion designer Tremaine Emory. Once the creative director at the streetwear brand Supreme, Tremaine has gone on to form his own brand, Denim Tears, which aims to tell the stories of the African diaspora through fashion.

His work has been recognized widely for its bold originality and Countercultural Drive. In our conversation, we talk about the psychology of how we validate ourselves in consumer culture, the layers of history held in terms of Black self identification, and what it means to leave the world looking different than when you started out.

Hey Tremaine, Helga. Really nice to meet you, and thank you so much for being here.

Tremaine Emory: Very nice to be here. Thanks for having me, Helga.

Helga: Absolutely. Nice to meet you.

Tremaine Emory: Nice to meet you. Thanks for the warm welcome.

Helga: We do that, because we're coming from so many different places, right, and situations. So, when we get somewhere, we need that kind of hug. I'm all for it. All right. When I started thinking about speaking with you, the easy thing to do is to go online and read a bunch of stuff. And that's not what I wanted to do. I wanted to find another way into some conversation and connection with you. So I did go online, but then I I found that there was a kind of poetry around you.

So, the things go. Emory is an American, is the founder. Emory moved, Emory served, Emory resigned, Emory was appointed, Emory co founded, Emory was named, Emory reigns, Emory reveals, Emory is part of, Emory has reportedly left, Emory was born. Wow, yeah, I hear it. That's you.

Tremaine Emory: Yeah, that's interesting.

Helga: That's cool. So let's talk about some of these things.

What is it for you to be an American? What does that mean? To be an American You feel yourself to be an American?

Tremaine Emory: Yes, I am. I'm human before anything, but I do feel extremely I am American. What is it to be American? To be American is to be wildly complex. I'll just speak from my experience. Yeah. In my family, the poorest moment in my family's life, let's say like, my parents when they were growing up, my dad when he was growing up, my great grandparents when they were growing up, compared to like, the world at large, it's still like, wealthy.

So, it's just Being an American is a paradox, because it's like, you live in your own world, unless you read and learn and educate yourself, so you can see what other people are going through, because you can get lost in what goes on in America, and there's way more to the world than what's going on in America.

So, um, That's why I say the first thing that comes to mind is, to be an American is to be, like, wildly complex. I feel like that's where the term, annoying American, comes from. And like, you're Americans who aren't self aware. I can see how annoying they are to people who are. Because how could you not be self aware of our privilege?

Self aware of our history? That affects our laws, and money, and military complex. Just name a thing. Name it. Education system, so on and so forth. Affects the world for a couple hundred years now.

Helga: And you're in that too, though. You're part of all of that as well.

Tremaine Emory: Yeah. Yeah, exactly. Whatever your level of political or social dissent is, if you still live here and pay taxes, you're a part of it.

You're part of the thing. The good and the bad of it. There's lots of good here. There's lots of bad. It's, you know, America's like A mirror, I guess in most countries, is a mirror of what it is to be human. A lot of good, a lot of bad, it's not just one thing. So, I think also to be American is like to be steeped in contradiction.

So I do feel American, but also I feel very specific American. I was born on the East Coast and I grew up in New York from age three months old. I spent my summers in Georgia, so my experience is very specific and very different. Just like a lot of people will say, hey, I grew up in St. Louis, my experience is different than yours.

So I'm just saying, me, I feel growing up on the East Coast, growing up in New York, being born in 1981, where I grew up, fleshing for nine years, then Jamaica, Queens, all that, I just think I have an experience and a viewpoint that's unto itself, type of parents I had, so on and so forth.

Helga: And what's particular to Flushing, and to those places, on Your sense of being American, in addition to this Georgia influence.

Did you go to Georgia during your summers or anything as a kid? Yeah.

Helga: And then you came back.

Tremaine Emory: Yeah, every summer we'd go and stay with my grandmother down to a very small town called Harlem, Georgia. One red light town, 1, 500 people. So spent summers down there with my older brother and my grandma, my cousins, my other grandma.

Both sides of the family, my parents grew up in the same town, knew each other their whole lives, went to the same high school that their moms went to, that type of thing.

Helga: And what's that imprint on you? After all those generations of them being in the same place and then you growing up in this very different place, where do you see that time and those summers in your life now?

Tremaine Emory: The imprint of it is that I have the open mindedness of a well rounded New Yorker. But I have also the moral compass and, um, work ethic of black folk from a small town in the South that had to totally rely on themselves to survive New and Jim Crow and even before Jim Crow. So that mix of dignity and self reliance.

Mixed with black pride and just pride as in dignity as a human being. And then worldliness of growing up in New York in the late 80s and 90s and 2000s.

Helga: What's specific or special about the 80s and the 90s and the 2000s in New York for you?

Tremaine Emory: One, pre internet. So, if you wanted information, you had to really go get it.

You couldn't peruse a culture and be like, that looks cool to do. You had to like, bump into it. You know, example, there's a store called Union that was started in the 80s. It was owned by James Jebbia, who also used to own Supreme. He used to own Union, and he started a store with a woman named Marianne.

And they sold all kinds of brands. And it would be proto streetwear, what people call streetwear. I don't like the term streetwear, but it's what people call streetwear. And um, I ran into that store in the late 90s, just walking through SoHo aimlessly, looking for something. And then I went into the store, met like minded people, saw clothing that I'd never seen before, made me feel something, and then I became a part of that.

Well, I saw that that clothing they were selling was my culture, some of it. And then I became a part of that culture, hanging out downtown. You had to, like, just be living life and be curious. You had to be really curious to have fun. Because there's the parameters of life. So there's the parameters of Jamaica, Queens, Farmers Boulevard, stuff in my household, school.

So then, if you wanted to, you could just live within those parameters. But to have a bigger life, or experience other things. You had to be curious and fearless and just put yourself in uncomfortable situations. You didn't know if it would lead to anything good or bad, but you just had to just try stuff.

So that was growing up in the late 80s and 90s in New York. Dangerous. Fun. Dangerous hell. So we moved to St. Albans, Queens. I guess it was towards the end of the crack epidemic in New York. It's when Mayor Giuliani started to employ the broken window stuff, and a lot of my friends were dying, being killed, shootings, sometimes it was drug related, sometimes it was just a beef.

A lot of guns were around, so it was just dangerous. I used to work in a liquor store that was like, like being extorted by With a plastic partition? Well, no, because this was the biggest liquor store in Queens. It's called Grady's Liquor Store. So, the way it's set up, it didn't have that. It literally was like a little supermarket.

You walk in. Okay. Supreme, he used to be coming up in there, doing whatever in the back. I think he was probably friends with or extorting the place. Every night, he wondered, oh, are we going to get robbed tonight? People that worked there for a long time say, oh, I remember that time we got robbed. So that was just my job, wondering, oh, are we going to get robbed tonight?

Walking home from work or from a party, maybe someone rolls up on you. And you're like, oh man, is this it? Then they're like, oh yo, what up? What up, Deuce? What up? Then they go drive off. Or they don't say anything. Because you heard stories of people walking home getting robbed, or worse. Like my school had metal detectors because someone had got shot the year, in the school or outside of the school, Thomas Edison, someone had got shot the year before.

I got a million stories, man, unfortunately. It's going to sound kind of corny, but I always say it, it's like Sandlot, the movie Sandlot, mixed with Boys in the Hood. A lot of kids of the same age, playing sports, playing games, hanging out, getting into mischief, fights, having fun, and then also people were dying.

I remember out of next door neighbor, he come by, he's a good man, but he was a drug addict, crackhead, and he come by, my parents, if you knew my parents weren't there, asked to borrow some money. Then my mom was like, Mom, so and so borrowed some money. She's like, don't worry about it. A couple days later, they put the money on the laundry line.

Because they're embarrassed, you know? Yeah, yeah. I saw this person fight their drug addiction. He was a great dude, though. I remember he thought I was smoking weed, which I didn't. I never did drugs. Those type of drugs, I only started drinking alcohol at some point. But he thought I was smoking weed. I remember he pulled me to the side and he's like, If I ever, he thought, really thought I was.

He's like, I'm going to tell your parents, you can't do that. I could hear the pain in his voice. He was speaking from his experience, you know? And he really cared. That's why I learned a lot about the human condition. And you can't see things just as good and evil, you know? I've been watching The Wire with my wife.

And then the fourth season, they start with a group of kids in junior high school. Their last year of junior high school. And it shows what happens to all of them by the time they go to high school. One, the main character, Michael, becomes like a gangster. One kid, uh, has to leave. Another kid goes His dad was a Legendary gangster actually doesn't want to live that path and goes and lives with the ex cop teacher.

And it just kind of reminded me the different paths people went on. And it was crazy because then the news came out about Jam Master Jay, his killers being convicted. I knew of both of them, and I grew up with one of them, I know that kid. So it was like, the wire had my mind there, and then um, I seen this guy's picture, I remember seeing him around, and then it just had me thinking about the neighborhood, and all the crazy stories, the unsolved stuff, solved stuff.

Yeah. Wow. Very wild.

Helga: Your story reminds me of of a thing that happened to me a couple weeks ago. So when I was leaving to come here this morning, I had a bag. It's my ride or die bag. I love this bag. And it's one of these things made of a recycled material. If anything happens to it, you pack it up, you send it back to the company, they fix it, and they send it back to you.

So you pay a lot of money up front. It's an investment. Cool. And so I picked that bag up, and then I put it down, and I brought something else. And I got to the train station and I said, well, what was wrong with that bag? And then I remembered a couple weeks ago, I was down on the platform at 125th Street and I was standing there, like everybody else, waiting for the train.

And there was a guy who kept walking back and forth in front of me. Whatever. Do your thing. And then he would look at me and he would smile and I smiled back and then he walked again and then I realized the smile was more menacing. He wasn't trying to be nice. There was another guy to my right who was kind of waving his hands around his head as if he might be crazy or on drugs or something.

And then My whole body just seized up and I'm looking and I'm looking and I don't understand what's happening, but I know something is wrong. And this sister sees me and she comes up to me and she says, I like your bag. And the first thing I'm thinking, are they together? What is this? And I look at her and I say, yeah, let me show it to you.

And we started to walk away. And she said, I don't know if you realize, but they were closing in on you. They were getting closer and closer and closer to you. And so I said thank you. I thanked her. Wow. And then I got in the car and I just started shaking. I was scared and I was angry. Because I was thinking, I'm up here in the community, and I'm trying to do the right thing, and I'm defending y'all, and I'm not going to be scared of my people, I'm not going to be run out of my neighborhood, you're a young black man, I love you, I love you, I'm here for you, I'm bigging you up, I'm holding down our community, and you want to rob me?!

For real. And then I don't know what to do with my hands. I don't know what to do. All that energy has to go somewhere. And so, today, I put my bag down and had to make a different choice because it brought me back to this place that held fear, anger, anxiety, and disappointment. And I think part of my work is also to figure out how to pick it back up.

And go where I'm going. Oh, regardless.

Tremaine Emory: And trust. Yeah, tough one though. But doable. It's doable, but it's tough. Yeah. Yeah, it's, it's interesting growing up in a community that has those layers of drugs and violence and, um, at times lack of solidarity, which is what you're talking about, because there's some communities that no matter how poor someone may be, they're not going to rob each other because they have that solidarity.

And it makes you go, why would you rob me? Not just like Helga, like anyone in your community, you know? But It really harkens back to the collective self worth of some minority communities, Black communities, don't want to speak for other communities, but some Hispanic communities, and so on and so forth, where you'll sit in your community and Attempt to rob a grown woman, any woman, or any person in your community that looks like you.

And then, I can imagine these same people, I'm gonna go on a limb, I'm gonna project that into their minds. They might have been the same people upset when George Floyd happened. Right. And going off about the man, the white man, police, and I'm just like, I don't know. I'm not saying none of that. Yeah, no, I got it.

Police are a problem. The 1 percent patriarchal white male mentality is a problem. But, the onus is still on you to Not add to it, right? It's like, uh, what? I think it's bell hooks. Pardon me if I'm wrong, but you can't dismantle the master's house with the master's tools, so I’m sorry to hear that happened to you.

Helga: I'm glad I'm here, right? That, and my hands can shake. I can leave my bag at home and figure out how to pick it up again, and I have tools to deal with that. Yeah. But then, uh, I want to ask this question, too. Like, the role of fashion in these kinds of situations where we have violence against one another. So, back in the day, people were robbing each other and shooting each other for their Jordans.

And so, all of our hands are in a system in which we create a kind of desire for things. And I think underneath that is really the desire to be seen, the, the need to say, I am. And we have this other world that creates A lifestyle, objects that feel out of reach, or that are aspirational for a lot of people.

And I'm asking you whether or not you see that there's a contradiction there, or that the creating of another object. that creates desire and a feeling of absence, that they're not mutually exclusive.

Tremaine Emory: Yeah, you bring up a very, very good point. I think in a lot of, uh, working class, poor neighborhoods, particularly of cultures of color, we value these grails, these holy grails, Rolex watch, designer clothing, more than we value Having a house, good credit, an education, because our self esteem and solidarity has been so pillaged by the system.

So I will put it on the system and capitalism and the media. And look at celebrity culture, right? The powers that be realize, hey, if we pump up these famous people, they can help us sell products.

Helga: Right.

Tremaine Emory: They can help us sell cereal, jackets. Everything. Everything. So we gotta make these people feel like they're more important and special than a person that's walking down the street.

So that the person down the street goes and buys this thing because so and so's holding the Kelloggs or the Wheaties, right? And that's how it works.

Helga: Yeah, but you have also been part of that system.

Tremaine Emory: 100%. 100%. As a sales associate, as a stock guy, as a consultant, as a creative director. I will say, I think the culture that I deal in more is about cool.

An example, when I was coming up, one of my dear friends, he told me one time, at the time he was hustling. and selling drugs, and um, we hung out all the time, became best friends, and he told me, I always wore clothing from the Goodwill, as a little boy, as a teenager, and to this day. If I had the time, I'd be going to Goodwill every week, I just don't have the time anymore.

I love going to Goodwill. And finding something for dirt cheap, you can't find anywhere else and you won't see anyone else with. And it's from a time when they made clothing really well. And he said one of his boys who was hustling too, and they were all a bit older, so they said, yo, your boy's cool, but he be wearing old clothes, what's up with that?

So. The thing I've been into, and I'm not saying it's complete individuality, but my thing's always been a bit left. Still consumerism, but now things I was into that I used to get made fun of, or people thought I was a weirdo for, have become mainstream. Vintage clothing's become huge. Now people are selling Marvel t shirts for 500, like an X Men t shirt, where I used to wear those my whole life because I I've been reading comic books my whole life.

Now that's become worth a lot. I remember I used to scour Vintage Ralph Lauren every Sunday on Ebay. I think I first got on Ebay in 2001, 2? And every Sunday, all the sellers would put up the Vintage Ralph Lauren, and I'd go through every page and buy stuff, dirt cheap. Stuff that sells for, you Hundreds of dollars now.

I was getting it for like 20 bucks. And I literally saw in real time all that change. But, not to say, still a part of it. So, I think people are being sold their self esteem because they don't have any. Not everyone though. Mm hmm. My parents, yeah, they like nice stuff. But, they weren't impressed. I remember one time, my nana, And my Aunt Connie, and a couple other people were in town.

So I used to go to Saks, the window shop. Or, and then when I got a Saks card, I'd be buying stuff that I shouldn't be buying. So I was like, oh ma, I'm gonna take them to the city, I'm gonna take them by Saks, 5th Avenue. And my mom was like, don't take them there, they can't afford it. And they don't care about that, just go have fun with them.

Don't try to impress them. So, that's always been the vibe from my parents. I interviewed my dad last Sunday, and he said it was weird for him coming to New York, because that was the first time he lived on land that his family didn't own. Because even though my family was poor, they owned the land, and they worked the land.

They had a well, chickens, sugar cane, watermelon. Peaches. They worked the land. My great grandfather's son, Emory, he'd be making molasses with his mule. Had a machine that the mule would touch to go around and turn the cane into molasses, and he'd go sell it to white folk. So my dad was like, it was weird when he moved out of Harlem, Georgia, and was paying rent and didn't own land.

They came to New York in 1981. They didn't own nothing in New York until 93, when we moved to St. Albans. And that's why we moved to St. Albans. It was a hectic neighborhood, but that's the only place my parents could afford. But see, now this leads me to something else. A lot of this performing of, wanna have a Rolex and stuff, and getting your self confidence, Again, it's also coming from the powers that be, the society.

We live in a white patriarchal society. Cuz, like an example, we lived in Flushing, Queens. This is how my dad had to get us our apartment. He was calling up places and my dad has a deep You know you're talking to a black man. He's a deep, southern voice. So he'd call up places and they'd just hang up on him.

This ain't in the 70s, this ain't in the 60s, this ain't in the 50s. This ain't during Jim Crow. This is in the 1980s in the melting pot New York City. Tracy Emory, a TV news cameraman, with his three kids. And his wife, never been arrested, upstanding citizen. He's calling places and they're hanging up on him because of his voice.

They won't meet him. So my dad, I remember he called our old landlord, Mr. Lee. Mr. Lee picked up. My dad said, do you rent to n***ers? I want to know. My dad was so fed up. My dad don't use that word. My dad said, do you rent to n***ers? I need to know. I need a place for my family. That's how frustrated. My dad's a sweetheart.

Again, this ain't in the seventies, fifties. So, my dad had a lot of dignity and self worth from how he grew up, but if your third generation grew up in the hood or the projects, and you work hard and you can't even get an apartment because they won't even pick up the phone or see you because they're screening you, so yeah, maybe you're like, hey, maybe if I had a Rolex or a Ferrari.

They see me different. They won't. But you can understand why someone would associate the value of a material thing to being maybe looked at different. It won't happen, but you can understand, or even being looked different within their own community. Great question. I agree with you. I think there is a lot of Attached to that, but I think it's there's a lot of reason for it.

I've gone through my own things I remember when my dad found out I had credit cards. He was so upset. He got so upset I was 18 years old. This is before the financial crisis. I go to LaGuardia Community College They got the desk there with the credit cards. I sign up for that. I got a Sachs card I got a Birdolph Goodman card.

I got a Barney's card. So my dad sees the bills And he started this. It's one of the only times my dad has flipped on me. Like, really screamed at me. He's like, you're paying for someone to fly around on private jets and hang out on a yacht with these high ass interest rates, da da da da. I said, Dad, I gave him my reason, and he's like, alright, be careful.

And instead of me just locking in, And living within my means, I wanted to have the Prada shoes. I mostly was spending those credit cards on clothing. And, yeah, I generally love style. So for me, at that time, so it's funny, at that time, a lot of the stuff I was wearing, I was getting made fun of. Like, when I bought the Prada sneakers that everyone wears now in 1999, cats had jokes.

I was wearing some, like, Dosie Gabbana jeans with, like, the back pockets on the front, so on and so forth. Wild stuff, right? Where now it's, like, kind of commonplace. People dress very different. No one was really dressing like that. I didn't care. I was doing it for me, but also it was still, it was a validation index for me.

Even though I might not have been trying to impress so and so next door, I still was trying to get validation from certain people who were up on it and for myself. And I was in debt for a long time, like years over that. But

Helga: Kool is for sale now too, right?

Tremaine Emory: Oh yeah.

Helga: And I remember passing And the

Tremaine Emory: interest rates are high.

Helga: I remember. I used to pass the Supreme store, and the line would not only be around the corner, it would extend for two blocks. And people would go early, and so you had the line that was going into the store. Then you had the person standing at the corner to monitor the line from the corner to the next block.

And I used to get so mad. First of all, I was like, what is this? Fair. That's a question. And then, do you vote? Are you just out here on this line to get this candy to keep you from being part of this society that wants to see change and that wants to participate? I'm not picking on this in particular. I'm saying it because this was a thing that you were also involved with.

Yeah. And just giving you a reaction I once had when I realized how It attracted a population of our society that I felt needed to be doing more than standing in line for a jacket.

Tremaine Emory: Yeah, great observation. I think that you have a very valid point. I remember Brexit was happening in the UK and I had a decent following then and I posted because people were complaining about the lines to vote.

I was like, well, you can wait in lines for sneakers, so wait two hours to vote. So I agree with you. I don't think anything's wrong with kids waiting in line. You know, especially in a certain era of Supreme, there was a culture of kids hanging out, meeting each other, especially pre internet, on the line.

I'm building friendships and stuff, but when they don't do that for things that affect their lives. And your life, Even more so, everyone's life. More than style does, or validation. I see why that's disheartening to you. It's disheartening to me. I don't see why we can't do both. No one was cooler than the Black Panthers.

They were cool as hell. The style. And they did food programs, they made voting, they policed the police, all kinds of things. And these were cool dudes, you know? You look at all those guys, those civil rights guys, they had great style. They were smooth, they were cool. You gotta be smooth to sit and talk and captivate people.

And get people to march. And take a brick to the face and not hit the person back. You gotta be cool to be able to convince someone to do that. You gotta be smart, you gotta be cunning. So, values have changed in our culture. Black culture and a lot of cultures of poor and working class people that were either colonized or came here through slavery.

And it's like we got to a certain point and then we've gotten far enough. Cause you know the thing is, people gotta remember. Rosa Parks had to meet her oppressors halfway. No one was like, yo, come to the front of the bus. She had to take that charge. So, even now in this current political state, a lot of people are complaining.

And nothing wrong with voicing what you're upset about, but then what are you physically doing? to meet your oppressor halfway. Cause who just gives up power? It's like being a kid. You're in a sandbox. Kids not just gonna give up the toy. You either gotta figure out how to take it through force, or through conversation.

So, like Pamphas and I'm like, let's try conversation. If that don't work, we'll take it through force. And force has been enacted upon us. MLK and his cohorts, we're gonna do it through conversation. And boycotting, and other ways to get what we want. And, you know, there's a choice, and there's a lot of debate on what's right.

I can't tell people what to do, I know. But I can't knock people who go the other route. Especially if they're being hurt. It's a choice. My choice is mine. So back to the, your question, I think. It's the value system. It's the phones. I give you an example. I'm 43. When I was growing up, boom, I'd be coming down the block.

I might have a book in my hand. No one was like, yo, you're reading? The word woke didn't exist. There was no, there was no need for it to exist because that's what people did. James Baldwin wasn't like, oh, you know who James Baldwin is? It's like, yeah, people know who James Baldwin is. It's literature. It wasn't a big deal.

Well, now somehow it's become a big deal if someone reads and they're woke and their consciousness is like, what? That's just part of being a human. Reading books to get knowledge, to apply it to your life, or to stimulate your imagination, or to take your mind off your life for a minute, read a book. Just like you go watch a film or go work out.

Something happened where like people become totally detached from that. I think that's a part of the problem, too, because when you read, you see that your struggles aren't your own, and you can connect to other people, and you also learn about history, and you learn what, you People have gone through so you could be, you could be on that supreme line.

Helga: Mm hmm.

Tremaine Emory: Mm

Helga: hmm.

Tremaine Emory: Because you couldn't wait on that supreme line because black folk wasn't allowed in the, not that there was an equivalent, there was clothing stores during Jim Crow that black folk couldn't go into. Right. Some of them wasn't even about, oh, there's a white entrance to black, and someone was just like, no blacks.

Mm hmm. So people had to do something And a big part of what they had to do was vote. So for me with the voting thing, voting's a choice, but you're making a choice to be disrespectful to your ancestors, your direct and your non direct ancestors, because they voted and they fought for us to vote so we can just walk around.

Helga: You're listening to Helga. We'll rejoin the conversation in just a moment.

Avery Willis-Hoffman: The Brown Arts Institute at Brown University is a university wide research enterprise and catalyst for the arts at Brown. that creates new work and supports, amplifies, and adds new dimensions to the creative practices of Brown's arts departments, faculty, students, and surrounding communities. Visit arts.

brown. edu to learn more about our upcoming programming and to sign up for our mailing list.

Helga: And now, let's rejoin my conversation with fashion designer Tremaine Emory. I have another question because I'm thinking about The story you just told about your dad calling around and looking for places to live for his family and he said, do you rent to n***ers? Yeah. That's a word that now has become very In my view, insidious, and I'm disappointed that that's where we are with each other.

When I think about your dad, what that word meant to your dad, I don't see it as an evolution. And why he said it that way. Why he said it that way. I don't see it as a thing that we can then reclaim and reuse without it having the same responsibility.

Tremaine Emory: I totally see your point of view. I think that. This makes you think of a conversation between Jay Z and Oprah.

Jay was on there and Oprah was, she's like, you're a smart guy. Why do you use the word n***a? And he said his reason and like, hey, we've taken the word, reclaimed it, and she was like, well, I feel a lot of black people that have been hung or killed, that's the last word they heard. That's why I don't want to hear it.

So Jay, his rebuttal was, I think we're both right. So I believe in and and and. Not and or, learned that from my neighbor Shira, she's like, you know Tremaine, you're an and and person, not an and or person, and so am I, and it really resonated with me what she said. It's interesting, because the two generations before me, my dad's generation and his mom and dad and them, they used the n word too, but they would use it playing spades, doing a fish fry, and they might be like, I ain't been to church in three weeks, you know, something like that, right?

And they wouldn't dare say it in front of. Not just white folk, just in front of anyone that wasn't family, right? And I think, again, black culture being commodified by everyone from Warner Music Group to Sprite to Apple. Part of that conification, new generation comes in. The morals and values that my dad's generation, they got obliterated by the crack epidemic and Contelpro.

So it started with Contelpro, part of Contelpro, was bringing in the drugs. And the RICO law, and these laws where an actress in Hollywood is smoking or sniffing cocaine, she gets a slap on her wrist. And if you're smoking crack in the hood, which comes from the same substance, You're going to jail for three years off rip.

If it's your second offense, now you're in jail for 15 years and you can't raise your kids because you're using the drug, the same drug that Gordon Gekko is using in the Hamptons. So you think all of this is attached or somehow related to this work? So then you have the breakdown of the Black family structure, where you got more Black men in jail than in college.

And you got the 80s, the crack epidemic. And then you have a lack of education. A lack of instruments, and you've got this beautiful thing, one of the most amazing art forms ever invented, hip hop. And you look at early hip hop before the crack epidemic, hippity to the hop, it was just that, right? Mmhmm. And then the message, you know, you had like the message.

Ooh, the message. Broken glass, everywhere. He started off the Don't push me. He started off the rap, broken glass, everywhere, describing the inner city. Black folks start going to jail at a higher rate than they ever had in this country in the 80s, late 70s and 80s. That gets reflected in the music. So the N word's in there because we've been saying the N word.

We've been saying N word since the juke joint, but now there's no OGs. Now grandma's raising her great grandkids and her son's in jail. Maybe her daughter's on crack, maybe her daughter's working two jobs. And now kids are getting raised by the streets. My dad wasn't raised by the streets, he was raised by a community in Harlem, Georgia.

My mom was raised by a community in Harlem, Georgia. Without even meeting you for the first time, I know, same story on your side. And in the 80s, that chain got broken by the crap epidemic. And education situation, the drug situation, policing, broken window theory, which got people in jail too. So I think it's all connected to Maybe mofos say n***as because they feel like n***as, and they didn't feel like it before that.

They felt like kings and queens. Like my grandma, I interviewed my grandma for something, and she's talking about how Ku Klux Klan came through Harlem, Georgia, and my great grandfather grabbed her and said, you're gonna sit on this porch. He sat there with a shotgun and said, if they cross that line, I'm gonna blow their heads off.

You see him? He's a coward. He works at the gas station. You see him? Wow. He works there. He's a coward. They all cowards who got them hoods off, but I know who they are. He pointed out all them white folk in them hoods and called them cowards and said, trust me, don't worry, they're not coming over here. And they didn't.

So he didn't feel like a n***a. A n***er. Son of Emory. Neither did my grandma, neither did my mom. You know, my dad didn't use running water until he was 12. They were poor. It was a healthy kind of poor. They still had healthy food, they had each other, they had fun. When school let out in June, they'd kick their shoes off and then put them on all summer.

They were fishin they were swimmin This, that, and the third. They used preservatives and smokehouse to get through the winter. Ain't like that. Growing up in the city, cause that's the thing to dream of, making more money. Black folks moved, they called it up south, moved to these major cities with these dreams and these promises of working in a Ford factory, working here, getting this work, and then the 80s happened and those jobs went overseas and also redlining happened and white folk left these neighborhoods or pushed them out of neighborhoods or got the jobs and then you add in crack to that, that's how you get where we're at.

You know, it didn't just happen out of nowhere. So I'm not making an excuse. No, I hear you. I'm not making an excuse for the use of the N word. But um, it goes back to the thing about clothing and validation, the clothing, the colloquialisms, all this becoming cool. What is a cool black man, right? And what's a non cool black man?

And if you really will it down and everyone's honest, fuck what white folk think. In Jamaica, Queens, you go to Farmer's Boulevard. Just stop and ask a young black person, what is cool? And we'll see what the first thing's out that mouth. Are they gonna say, having a good credit score, so, owning a house, and having health insurance, or having a will, and then having life insurance so when I pass away, my family don't go in debt trying to bury me.

And I have to do a GoFundMe. So instead of making sure I got on Jordans, I put 200 into a life insurance policy. So when I go, my family got some money and could bear on me. And someone gets some money, might get 500, 000. You know? Stuff like that. Do people think that's cool? I don't know. Even with the upbringing I had, I still had to reprogram myself out of the validation game.

A lot of it is to feel better in front of other folk, because you don't feel good about yourself. So that word ties into that, I think. I still use it, unfortunately. And at times where I'm self aware and self reflective, I'm like, why do I use it? Well, I grew up saying it. I grew up around people saying it and hearing it.

I don't have to. And hearing someone, how it makes you feel, sends me right back to thinking about why do we use the word, why do we use the word.

Helga: Where's the first place you went when you left this country?

Tremaine Emory: London, London, 2010. Yeah, the first time I left the country. I was 27, 26. Yeah. And what brought you to London?

I used to work for Marc Jacobs. I was a sales associate at the time. I started off as a stock guy. And his business partner, Robert Duffy, moved me and my partner at the time to London to work at the MJ stores over there.

Helga: And what are some of the other places you went to before you came back here?

Tremaine Emory: A lot.

All over Europe, Shanghai, Hong Kong, Japan. Bali, Germany, Spain, keep going.

Helga: So you have gone to all these places and then you come back and you're in this situation where you're a creative director. You're someone who can decide and who's making taste for other people. Given all of the things that you've shared about who you are, who your people are, where you come from, what did it mean for you to be in that position?

And to add on to that, the fact that now you've been to all these other places in the world, and you're still the person who went to Harlem, Georgia. How did all of those things come together?

Tremaine Emory: I realized upon re entering America from being in Europe for eight years, and traveling the world, and then changing my career, becoming a creative consultant, Doing all the things I did, becoming an artist, designer, that there wasn't many people where I'm from doing what I do.

And a lot of what we were doing was, brands were like, wanting our thing, to help them sell something. I just wanted to give people of any color a chance. A part of my perspective, the stuff I make with Dim Tears is in my whole perspective. I don't sit and think about the plight of being a Black man and the glory of being a Black man, an African American, every second of my life.

But -

Helga: You also don't have to.

Tremaine Emory: I know, I was like, I don't have to, yeah. I don't think, I don't think Francis Ford Coppola thinks about the mob all the time. I wanted to give this culture that, I wanted to People call it streetwear, fashion, whatever, that is so influenced by Black culture. There's no brands that are considered really cool, that are poppin really, that are ran by a Black person, coming from the Black perspective.

It's always like, they'll do a Biggie t shirt, a Mar a Luther King hoodie, they'll get this rapper to be in the ad, and whatever, and that's cool, but it's not inclusion if you're making money off it. It's Profiteering. And that's cool, you know, like, we live in capital size, so we're like, mine's inclusion because, yeah, I'm making money off it, but also like, my brand director is a black woman.

Our junior art directors is a black woman. I can keep going. Black people work for me. Some white folk work for me, too. I had a Mexican slash Native American man that works for me, and I've worked for these brands. Their makeup doesn't look like mine, and I'm putting out work on the same thing. So why is it that I'm the only brand that got multicultural C suite or design floor?

Well, if you do it, they don't have to. Exactly. So that goes back to the thing where it's like, meet your oppressor halfway. So I might speak out against things, but I'm actually doing something. I can speak out. I have the right to speak out, in my opinion, because I actually do things to change the way the world looks.

And when I die You know, I almost passed away a year ago, and if I would have died, I didn't change the world, but I know a part of this world that I started working in, I left it looking different than when I came in it. That's a fact. Just like my brother Virgil did, my brother Asaad, Grace, and Sean Medina, I'm just naming people I know that are part of my tribe of creatives, that are people of color.

Martine Rose, Grace World Gwana, we're leaving it different. It wasn't like this when we came in. Yeah, so that's me coming back from Europe. I was like, nah. The hardest thing feels like to make a brand cool, relevant, and meaningful in this space. It feels like a Almost impossible challenge. That's what I want to do.

And that was part of the inspiration behind starting Denim Tears. When my store opens, you're going to see kids of all colors waiting online for something that, that's got a story. Even if they're not wearing it because they care about their story, there's still a billboard for that story. And I think that's me leaving the game different than when it came in.

And it's considered cool, it's considered Well, by me it's considered cool, and it's considered, I believe, great design. That's my validation index that I'm developing is, what do I feel about it? I'm not worrying about everyone else's opinion outside of, like, my little tribe. So, that was the thing, coming back from Europe was to This is what I feel I can do with my skill set, to make a living in a fulfilling way.

Probably feel it's no different than, not comparing myself at all to him, but Spike Lee. Or Julie Dash. You know, she's not as well known, but she's just as incredible as Spike. Julie Dash made the first Black female directed Hollywood film, Dollars at a Dust. And she put something there that wasn't there before.

That's change. Just like Spike did. And others. Before them, Mary Van Peebles. Yeah, that's my thing as far as, right now, as far as my creative outlet, my art.

Helga: What's a thing that you do, Every day that every person can do.

Tremaine Emory: Be grateful. I went to the doctor this week. He's a cool doctor. I'm going to the doctor all the time and he looked at my chart.

He's like, man, you're a walking miracle. You shouldn't even be here. I said, yeah, I'm super grateful for it. And I said, you know what? When I was in rehab for those two months, What happened? I had a lower aortic aneurysm. Which is pretty serious. Nickname of it's called The Widowmaker. But um, I survived it and I said to him, You know what?

I've seen people in the rehab that are worse off than me. So, I don't feel sorry for myself. And I feel I owe it to people who are worse off than me to work as hard as I can. Doing my physical therapy, taking care of myself. He's like, there are people worse off than the people you saw. And um, the rehab actually, he's like, you know who they are?

He's like, the people that didn't make it to rehab, the ones that died. I was like, oh man, you're right. He's like, yeah, so he's like, you got the right attitude. So that's the main thing I could tell every day. You can't guarantee that you're going to want to get up and work out or get up and eat the right food, but you could be grateful.

You could be grateful that there are things to be grateful about. Or there's things you can do about the things that hurting you in your life. You have choices. So that's the thing people, I think, can do is be grateful. Just be grateful.

Helga: Anything you want to ask me?

Tremaine Emory: I'm really flattered that you asked me to be on a show because you're such a illustrious cast of people that you've talked to. So to be included with these, uh, amazing people is, uh, an honor. I appreciate it. Uh.

Helga: I want to say one thing that you, you've said that I really appreciate. Appreciate. You said, there's nothing I've done that I've done on my own.

Tremaine Emory: Yeah, people get caught up in, I did this, I did that. You don't do nothing on your own, and no idea is original, and you need help to do everything. It's like, I feel accomplished. My accomplishments are the culmination of my work. Teamwork. That's just the way it is. Michael Jordan's Hall of Fame speech, the first thing he said was, Each one of these championships you saw Scotty next to me.

That's the first thing he said. The greatest basketball player of all time. Muhammad Ali, he had a trainer. Someone had to hold the bucket, someone's got to do his cuts. We live in a society of, I did it on my own, and I did it off my own back. I don't care what you do, there's this help, and you better appreciate that help.

Because if you do something great, that means you had some great help. You know, I'm really appreciative of all the people I work with. Business partner Anthony, um, All my colleagues at Dempsey's, and all my mentors since I was a teenager that I've had. I started with my parents and my grandparents, and then all the people I met.

A couple teachers and friends I've met that have inspired me and given me a book, taken me to an art show, told me to take my butt home, you know, get off this corner, you know, whatever it is. You know? For real.

Helga: Emory is an American. Emory is the founder. Emory moved. Emory served. Emory resigned. Emory was appointed.

Emory co founded. Emory was named. Emory reigns. Emory reveals. Emory is part of. Emory has reportedly left. Emory was born. Thank you, sir.

Tremaine Emory: Thank you. That's beautiful. That's you! Really cool. Thank you.

Helga: That's you! That's not me, that's you!

Tremaine Emory: I really enjoyed it.

Helga: I'm so glad you were able to come.

That was my conversation with Tremayne Emory. I'm Helga Davis. Join me next week for my conversation with Brown University Professor of Music Enongo Lumumba Casango, also known as rapper, producer, Samus.

Enongo Lumumba-Kasongo: So in that weird limbo period where I had graduated and I was trying to find my voice and trying to figure out what was next, I Developed at least enough self knowledge to know that if I wanted to express myself, I wanted to express myself as me.

And who I am is just a big nerd at the end of the day, so I need to fall in love with whoever that person is, even if she's flawed or is not the coolest person on the planet. I want to celebrate that I'm someone who loves to read, I love comic books, I love movies, and leaning into that as my persona felt like a really meaningful and powerful part of my own self development.

Helga: To connect with the show, drop us a line at helga at wnyc. org. We'll send you a link to our show page with every episode of this and past seasons. And resources for all the artists, authors, and musicians who have come up in conversation. And if you want to support the show, please leave us a comment and rating on any of your favorite podcast platforms.

And now, for the CODA.

Mik Awake: My name is Mick Awoka, and I wrote the article, The Near Death and Rebirth of Tremaine Emory, for the December January 2023 issue of GQ Magazine. Here's a short excerpt from the article, which you can read in full by visiting gq. com slash rebirth.

Narrator: The aorta is the largest blood vessel in the body. Your heart appears to almost hang from it. The word aorta comes from the Greek, to hang, like a flower too heavy for its stem. Even now, as you read this, blood pumps constantly through your aorta, traveling via an elaborate ductwork of arteries to nourish organs, fingers, eyes, brain, before circulating back toward the heart, in a life sustaining process as quiet and perfect as the universe.

The technical term for what happened in Emory's body that night is an aortic dissection. It's a medical nightmare, as rare as it is lethal. 1980s sitcom star John Ritter died of one, as do an estimated 13, 000 people in the United States each year. Back in the day, doctors used to call it the widow maker.

The first hours after a tear in the aorta's inner lining are the most crucial for survival. The ambulance pulled to a stop outside the Tribeca building, red lights dancing against the darkness. Here was the promise of relief. Answers. The hope of survival. There was a tense moment when McConnell accidentally locked herself out of the apartment with the paramedics, forcing Emory, sopping wet with no feeling in his legs, to crawl across the floor to open the door.

The EMTs began firing questions at him. Was this his apartment, they asked. Had he been doing drugs? Emory was rolled outside to the waiting ambulance in a wheelchair, and during his transfer from the chair to the vehicle, he sustained an injury to his toe. He couldn't feel anything below his waist. But blood was streaming from the wound.

In the hours ahead, the toe would turn gangrenous from lack of blood flow, and eventually its tip fell off. Part of what makes an aortic tear so lethal is that emergency room doctors often fail to discern the condition, prioritizing more common ailments like heart attack. Relatively young and healthy, Emory was still conscious, still breathing.

With McConnell at his side, he waited as medical staff moved them from one hallway to another. The hours passed. The couple lost track of time. Meanwhile, the crisis inside Emory's body was worsening. According to Emory and McConnell, several hours passed like this before the morning shift rotated on and a black doctor who saw Emory became alarmed by the numbness in his legs.

and an increasing pain in his lower abdomen. She had a sense of urgency that no one else did, McConnell recalled, and the stomach pain seemed to really get it on her radar that she needed to move fast with this guy. When results of the CT angiogram returned, highlighting the state of Emory's vascular system, The intricate weave of blood carrying arteries, capillaries, and veins, McConnell vividly remembered the doctor's reaction.

The look on her face was panic inducing. Scans would reveal that the tear in Emory's aorta began in his chest and extended down through his pelvis and femoral artery, beyond the edge of the x ray. What the doctors didn't say aloud, their actions, suddenly urgent and decisive, Filled in the blanks. Within minutes, Emory was in an emergency transport vehicle headed to New York Presbyterian Weill Cornell Medical Center on the Upper East Side for surgery.

It was at this point, alone in an ambulance racing toward the unknown, that Emory took out his phone and began reaching out to everyone he loved. For what he assumed might be the last time.

Helga: Season six of Helga is a co-production of WNYC studios and the Brown Arts Institute at Brown University. The show is produced by Alex Ambrose and David Norville with help from Rachel Arewa. and recorded by Bill Sigmund at Digital Island Studios in New York. Our technical director is Sapir Rosenblatt, and our executive producer is Elizabeth Nonemaker.

Original music by Meshell Ndegeocello and Jason Moran. Avery Willis Hoffman is our executive producer at the Brown Arts Institute, along with producing director Jessica Wasilewski. WQXR's Chief Content Officer is Ed Yim.

Copyright © 2024 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.