Apr 23, 2012

Aarhus, Denmark

A two-story stone building. When it first opened in 1852, it was known as the Asylum of Jutland. Today it is part of Aarhus University Hospital's psych ward.

I enter with a friend of mine, Knud, a retired Danish pastor in his 80s. Knud knows the hospital quite well; over the years, a number of his parishioners were institutionalized here. Knud has driven me to the hospital because he wants to show me something I can't see anywhere else in the world.

Apparently, in addition to housing 200 patients, this compound is home to a small museum. A small, but quite special museum.

We start on the top floor. We walk through the floor plan as it existed in the 19th century - we see the beds patients slept in, the dishes they slurped soup from, the straight jackets they were belted into. A cabinet of room keys. A set of scales to measure out meds. Pretty normal stuff for a mental hospital at the time.

We start on the top floor. We walk through the floor plan as it existed in the 19th century - we see the beds patients slept in, the dishes they slurped soup from, the straight jackets they were belted into. A cabinet of room keys. A set of scales to measure out meds. Pretty normal stuff for a mental hospital at the time.

On a low shelf I spot an ECT machine which meted out electroshocks to 20th century patients. Vaguely interesting, but not so impressive to look at - basically just a box with dials and buttons and gauges. I politely smile at Knud, but I've seen this kind of stuff before.

On a low shelf I spot an ECT machine which meted out electroshocks to 20th century patients. Vaguely interesting, but not so impressive to look at - basically just a box with dials and buttons and gauges. I politely smile at Knud, but I've seen this kind of stuff before.

We descend down the stairs to the bottom floor. And here's where it gets interesting.

The bottom floor is … an art gallery.

I see paintings, but also sculptures, tapestries, a few sketches. Everything on display has been created by mentally ill artists, the majority of whom were - or still are - hospitalized in this very compound. There are 850 objects on display, but that's only a fraction of the 9,000-piece collection.

Now I've vaguely heard of "art brut" or "outsider art" - a genre devoted to the artwork of mentally ill people, but I've never completely understood the appeal. I find the assumption underpinning it - that mental patients are by default tortured artist geniuses in disguise - difficult to swallow.

What is fascinating about this collection, though, is the assemblage of individual stories it tells. These artists - the gallery is organized by artist - spent years, if not decades, locked up here, battling personal demons. And whether or not their artwork has any artistic merit, each piece tells a tale of how its maker felt about the micro-world of the hospital, and ultimately, how he or she escaped it.

Take Jan Nedergård.

Unlike many of the other artists in the collection, Nedergård was a professional painter before he was hospitalized. An acute alcoholic, Nedergård cycled in and out of the institution, often against his will.

Unlike many of the other artists in the collection, Nedergård was a professional painter before he was hospitalized. An acute alcoholic, Nedergård cycled in and out of the institution, often against his will.

His paintings look … well, how you'd expect the paintings of a depressed alcoholic artist to look. Dark colors, jagged lines, religious imagery, vague and cryptic nouns ("JUDGEMENT" "POVERTY" "DEATH"). Anarchic, expressive, messy, angry.

His paintings look … well, how you'd expect the paintings of a depressed alcoholic artist to look. Dark colors, jagged lines, religious imagery, vague and cryptic nouns ("JUDGEMENT" "POVERTY" "DEATH"). Anarchic, expressive, messy, angry.

Nedergård died in 1986 at the age of 35. The description hints that he did not die of natural causes. His "early death was probably caused by the hard life he had lived." His only escape from his brutal reality was death.

On the other end of the spectrum, there is Hans Heinerik Nielsen.

Near the end of the Second World War, Nielsen - who was a saboteur, working for the Danish Resistance - suffered severe head trauma. He woke up convinced that (a) he was a painter and (b) he was the son of then Danish King Christian X. While he lived in this hospital, Nielsen wrote letters and cards to (what he thought were his) royal family members. He even mailed whole paintings on royal birthdays and other special occasions.

As you might expect, his paintings were mostly on what the description calls "Royal themes," that is, he painted royal portraits.

Unlike Nedergård's paintings, Nielsen's are done in bright colors. "He wanted to convey to spectators the joy and happiness of life," the museum description tells us. He thrived while hospitalized, based on the delusion that his confinement was just some petty misunderstanding that would be cleared up once everyone realized who he was.

At some point, Nielsen started wondering why he wasn't getting a government paycheck, like the other royals. He also received a formal letter from the "Head of the Royal Household" commanding him to stop writing to them. He reluctantly did. Apparently, he found some solace in the fact that the people close to him kept calling him "Prince Heinerik" until his death in 1985.

But the most interesting and dramatic life story exhibited here is Louis Marcussen's.

Early in his life, Marcussen was trained as a naturalistic painter. He painted vases of flowers that looked to me like the kind of boring and nondescript art you'd find in a doctor's office.

At the age of 31, Marcussen traveled to Argentina, hoping to make his name as an artist. After three years there, he was broke and broken. He slept outside under a tree; he couldn't afford to eat; he began to hear voices. He returned to Denmark, was diagnosed with schizophrenia and found himself in this hospital in Aarhus. He would stay here for the next 56 years.

So long was Marcussen lodged here that he dubbed himself "Ovartaci." The name played on the titles of the honchos at the hospital - the Head Nurse (oversygeplejerske) and the Chief Psychiatrist (overlæge). "Taci" derives from tosse, a colloquial word for a mental patient. Ovartaci, then, is a pun of overtosse, which translates to something like "the Head Fool," or "the Super Loon," or "the Crazy-in-Chief."

Ovartaci had ambivalent feelings about his half-century confinement. Early on, he clashed with hospital authorities, who tried to inhibit his expression and conduct. It didn't help that hospital life was, as the museum itself admits, filled with "isolation, prison-like social relations, [and] the constant fight for individual space." But as much as Ovartaci bucked against hospital life, he insisted that he didn't want to leave, that he belonged there.

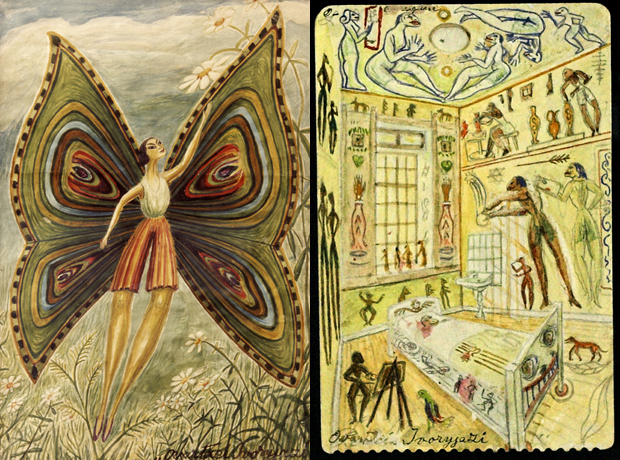

While rooted in this building, Ovartaci - who was a Buddhist - believed that his soul migrated and reincarnated through thousands of lives - across time, across space, across gender, even across species. At one point, he was a tiger in India. At another, a butterfly in Spain. He helped build the Egyptian pyramids. His father was a blacksmith on the moon.

It all came through in his art.

One recurring image in his work was of a thin but curvaceous cat-woman with almond-shaped eyes.  Ovartaci saw himself as a woman, so much so that - about halfway through his time at the hospital - he used carpenters' tools (a wedge and a mallet, as a film in the exhibition so casually shows) to castrate himself. In the ambulance on the way to the Emergency Room, he complained of no pain. Reportedly, he never regretted the decision.

Ovartaci saw himself as a woman, so much so that - about halfway through his time at the hospital - he used carpenters' tools (a wedge and a mallet, as a film in the exhibition so casually shows) to castrate himself. In the ambulance on the way to the Emergency Room, he complained of no pain. Reportedly, he never regretted the decision.

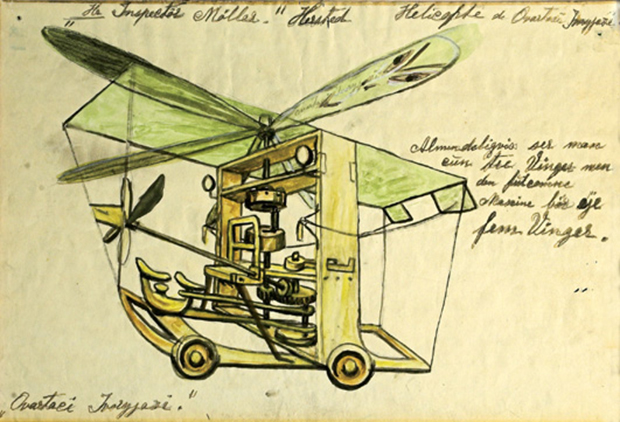

Eventually, as hospital administrations changed, so too did the living conditions. Ovartaci was given a private room, a personal set of keys to the wards, even a bicycle for short unchaperoned trips off the premises. He was allowed to self-medicate. He was given his own studio to work in full-time. They even delivered meals to him there.

That didn't stop him from drawing up elaborate escape schemes. One of them was a Leonardo da Vinci-style helicopter he designed and constructed himself.

Despite the effort he put into it, the helicopter never took off. It's unclear whether - deep down - he really wanted it to.

By the end of his life, Ovartaci's paintings, sculptures, and poems took on a life of their own. And despite the fact that he grew less and less sick as he grew old, he refused offers to leave the hospital to try to earn his living as a professional artist. In his mind, he didn't need to. He died at the hospital in 1985, at the age of 91.

Stuck here for unfathomable lengths of time, these patients found their own ways to escape. For Nielsen it was as tiny as a simple "Your Majesty." For Nedergård, it was as drastic and violent as suicide. For Ovartaci, it was more complex - as if he was just docking his body here, so he could satisfy this more profound spiritual wanderlust. He didn't need to escape, because he was already so very far away.

All photos courtesy of the Ovartaci Museum.

Special thanks to the Ochsner family of Aarhus, Eddie Danielsen of the Ovartaci Museum, and Phil Loring, Curator of Psychology at London's Science Museum.