Apr 4, 2012

Uppsala, Sweden.

An internet café.

I finish rifling through my email just under the wire. But how to use the precious few minutes left before the blinking timer reaches zero? I do something I almost never do: check my spam folder.

I find an email titled “FW: RE: FW: PORK CHOPS” from my uncle, a man who never met a chain email he didn’t forward.

When I open the email, I see a series of bizarre images of a tiger suckling a litter of piglets.

Weird. Possibly fake. But intriguing.

The screen freezes because I’m out of time.

I walk out into the sunlight and putter around the old college town of Uppsala. I soon find myself at the 13th century cathedral. I enter and, after taking a few steps, realize I’m standing atop the interred remains of 18th century botanist Carl von Linné.

You might remember Linné from your high school biology textbook. He was in there right next to “binomial nomenclature,” which he popularized. Homo sapiens, for instance, was a name he invented. Same with Cannabis sativa.

So fond was this Swedish botanist of giving two Latin names to everything on earth, that the byline on his botanical works was not Carl von Linné, but his own Latinized binom, Caroli Linnaei. You probably know him by another of his Latin monikers: Carolus Linnaeus. (Fittingly enough for a botanist, Linné, Linnaei and Linnaeus are derived from the Swedish word lind meaning linden tree.)

But however much we remember him as a namer, Linnaeus was also something far more ambitious: he was a sorter.

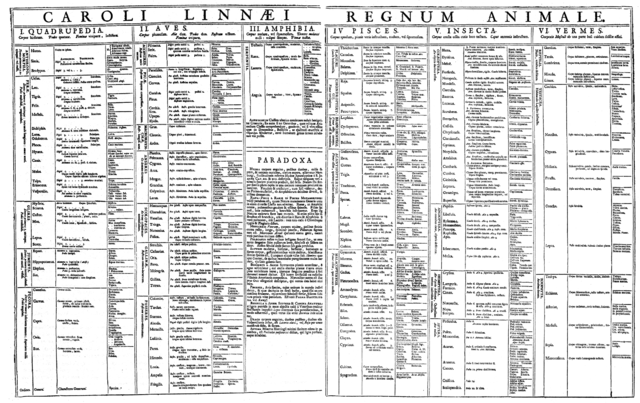

Table of the Animal Kingdom (Regnum Animale) from Carolus Linnaeus's first edition (1735) of ''Systema Naturae',' via Wikimedia Commons.

To Linnaeus (who was what we would today call a creationist), the world had an underlying divine order. It was his job, he thought, to master that order. To catalog every living being. To lump and split. Humans from non-humans. Tigers from piglets.

To help him in his grand plan to sort the world, Linnaeus enlisted the help of many far-flung correspondents who would send him specimens that he’d house in Uppsala’s Botanical Garden. Naturalists would send him detailed descriptions, with attached sketches and diagrams, if not samples. To one who sent him some microscopic copepod specimens, Linnaeus wrote:

You, in these minute and almost invisible beings, have acquired a more lasting name than any heroes and kings by their cruel murders and bloody battles. I congratulate you on this, your own stupendous victory, over the barbarous ignorance which hitherto has held the philosophic world in subjection.

Not one for understatement, Linnaeus.

Every once in a while, Linnaeus would get a report that he doubted or otherwise didn’t know what to do with. Perhaps it came from a disreputable source. Perhaps it defied his classification scheme. Perhaps it seemed too fantastic or just too weird to be true.

He grouped all of these reports together in a category he dubbed Paradoxa. The list included:

- satyrs (“hairy, bearded, with a human body, gesticulating much, very fallacious”)

- dragons (“with an eel like body, two feet and two wings like a bat”)

- the hydra (“two feet, seven necks and as many heads, without wings, … [even though] Nature, always remaining true itself, has never in a natural way produced several heads on one body.”)

- the frog-fish (“very paradoxical”)

and best of all

- the pelican (“with its beak [a pelican mother] wounds its thigh in order to quench the thirst of its young with the blood flowing out”)

Linnaeus was mostly right to suspect these reports – satyrs don’t exist, but the frog-fish does (Pseudis paradoxa); the pelican does exist, but it doesn’t drink blood. None of that could have been easy to figure out from his perch here in Uppsala.

Which brings me back to that email forward. After my hour at the internet café expired, I couldn’t shake the image of those little piglets suckling on their tiger mom. Was it photoshopped? How odd that about 275 years ago, Linnaeus was nearby here, squinting at the 18th century equivalent of an e-mail about vampire pelicans, wondering pretty much the same thing.

A few hours later, back online, I saw Snopes.com’s take on the tiger and the piglets. Turns out, the photos are real, but part of a contrived scene staged for the shock value. One of the many creative but controversial and possibly cruel exhibits at the Sriracha Tiger Zoo in Chonburi, Thailand.

As in many things, the truth was a lot less fun than the mystery. A lot less fun and a lot less challenging. But for just a few hours, I got a taste of what it’s like to wonder.

Alas, my spam folder decided to sort this email out of my life. Is there no room for paradoxa anymore?

- Don't pelicans look a little like aliens? Above photo by ahisgett/flickrCC-BY-2.0

- While online later, I also discovered that the collective noun for pigs is not litter, but farrow. Who knew?

- For more on the taxonomy of the weird, see Harriet Ritvo’s The Platypus and the Mermaid, and other Figments of the Classifying Imagination

- On finding wonder in the modern world, see Lawrence Weschler’s Mr. Wilson's Cabinet of Wonder: Pronged Ants, Horned Humans, Mice on Toast, and Other Marvels of Jurassic Technology